The Gum You Like: a Letter from the Western Borders of Shanzhai

This essay was commissioned by Berliner Gazette for its special project Black Box East. The German translation of the text, originally published in May 2021, can be found here.

With special thanks to Xiang Zairong, whose brilliant research and outstanding wit led me to write this utterly shanzhai feuilleton

By the beginning of summer 2020, the reality of the pandemic was more than obvious yet most of the people I was talking to were hopeful about things getting better quite soon. I was waiting for the acceptance letter from East China Normal University that I would soon receive, and moving to Shanghai still seemed to be a matter of several months. But the overheated suspense kept delusions at bay and nurtured another kind of acceptance—the gut acceptance of borders staying closed for much longer.

At the time I was involved in preparing the launch of EastEast, and that helped me stay both pleasantly distracted and exhausted. One soft evening in late May, I lay down with my laptop and joined a zoom talk my friend Xiang Zairong was giving at the China Centrum Tübingen. It was a talk on the phenomenon of shanzhai, “an imitation of an original that doesn’t exist.”

Since the early nineties, post-Soviet Eastern Europe has been flooded by shanzhai goods. The ubiquity of Chinese-made cheap products with gigantic logos and extravagant design, from Abibas shoes to Ponosonic electronics, was so total, so unquestionable, that I barely ever thought about it. As a kid, I was taught to treat the gaudy polyester garments of this kind as tasteless, though I would oftentimes feel genuinely fascinated and slightly envious seeing people wear those. The first time I ever thought about shanzhai in all seriousness was when I first came to China, in my early twenties. Apart from facing the eerie familiarity of communist aesthetic legacy, I was suddenly swept by the realization that Chinese and Ukrainian lower-income people wore absolutely identical clothes.

This détournement of Chanel and Gucci logos, these generic Hollywood faces on photo-printed tops and dresses, newspaper-pattern bags, bold colors and cuts: I’ve never seen anything like that in America or Western Europe, but I did grow up seeing all these every day. Later, I started thinking more about the dynamics of shanzhai. It was indeed never about copying. Chinese producers were using the popular globalized motifs the way 18th century French artists experimented with chinoiserie: by putting together what seemed to be familiar features, real and imaginary, of something Chinese that had little to nothing to do with China itself. Shanzhai is occidenterie: it plays with what appears to be most “Western,” be it popular luxury brands, meaningful inscriptions in English and sometimes even French, or thought-after Apple logos. And the major consumers of it are the not-so-Western post-Soviet lands.

Working class and small town Ukrainians crave occidenterie. This affordable westernness of shanzhai brings them closer to the “West” than the European Union Association Agreement, visa-free EU travel, or IMF loans ever could. Post-USSR countries make up the largest percent of AliExpress clientele, and their provincial fabric markets look just like Chinese ones. For many centuries, Chinese inventions would travel westwards, getting transformed, appropriated, adjusted. This transformed and adjusted westernness is ultimately a reappropriation—and a new invention—that all at once fits the post-Soviet desire like a glove. It is a materialized dream.

A couple of weeks after listening to Zairong’s talk—that included his extensive reference to the California Dreamin’ leitmotif in Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express—I went to a local fresh produce market to get some vegetables. Having picked the best tomatoes, I raised my eyes to the salesgirl and my jaw dropped. She was wearing a T-shirt with a huge inscription in English: “PARIS is a state of mind.” Paris of course is nothing but a state of mind, no matter if you are selling tomatoes in a Ukrainian town or buying them there, no matter if you are drinking champagne in the 8th arrondissement or taking a stinky train to Nezhin. Paris is just an inscription on a T-shirt designed and manufactured in China. This Paris resonated so much with the California of Chungking Express that I wanted to take a picture of the girl and send it to Zairong immediately. However, I couldn’t do that: both taking it without her permission or asking her permission to take it would confirm the distance or difference between us, and in that sense, I am a shitty anthropologist. It was as if the object of my study was immediately speaking to me: “Do you think you are any better than me, little bitch? You are paying cash money to get something I got and you don’t: vine-ripened fragrant tomatoes.” (I do think it’s important to include her imaginary voice here.) I tried to take a cowardly picture of this enigmatic shirt from a distance, but then I had a better idea. I decided to go to the fabric market around the corner and check if there were any similarly admirable goods.

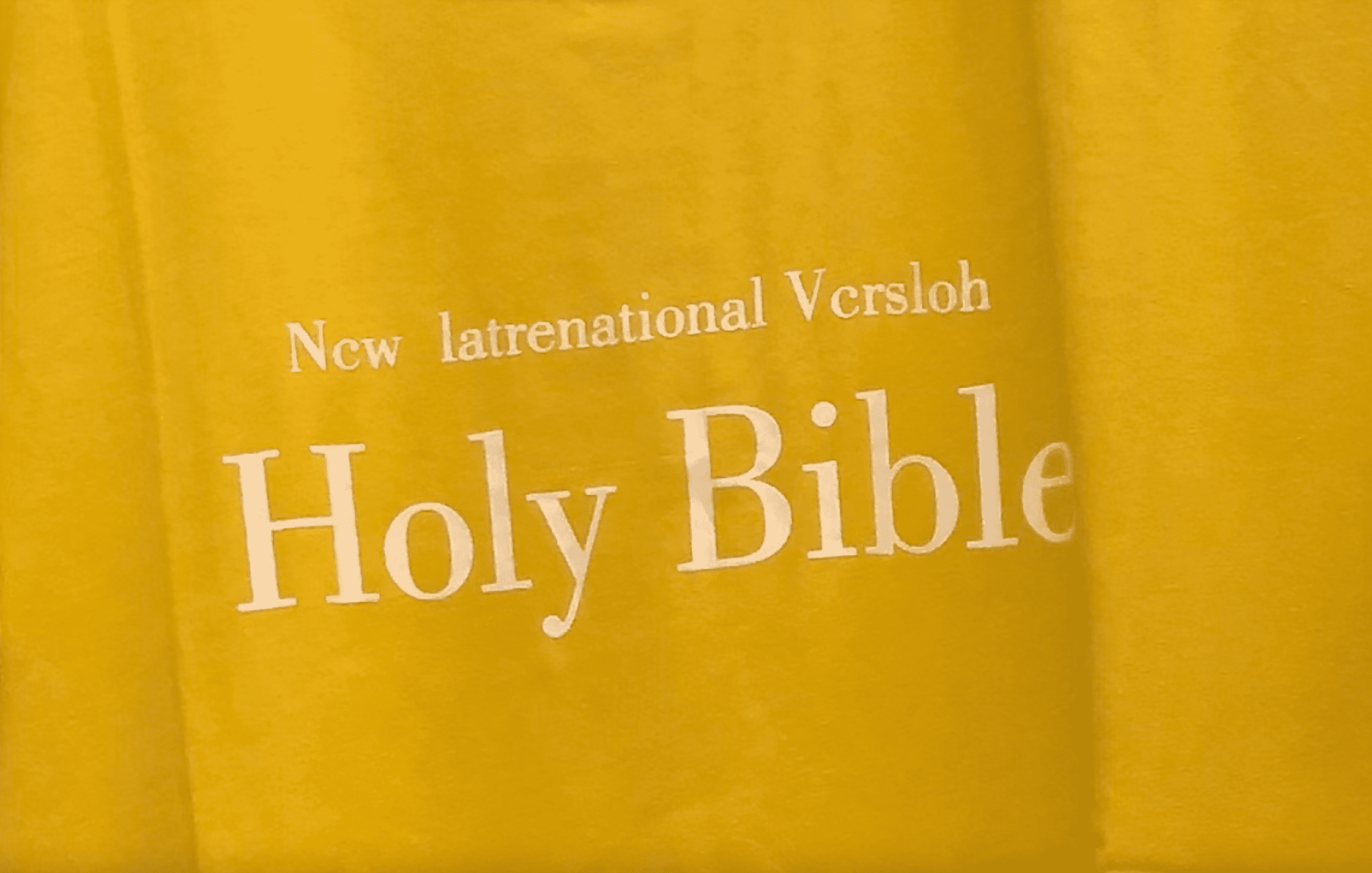

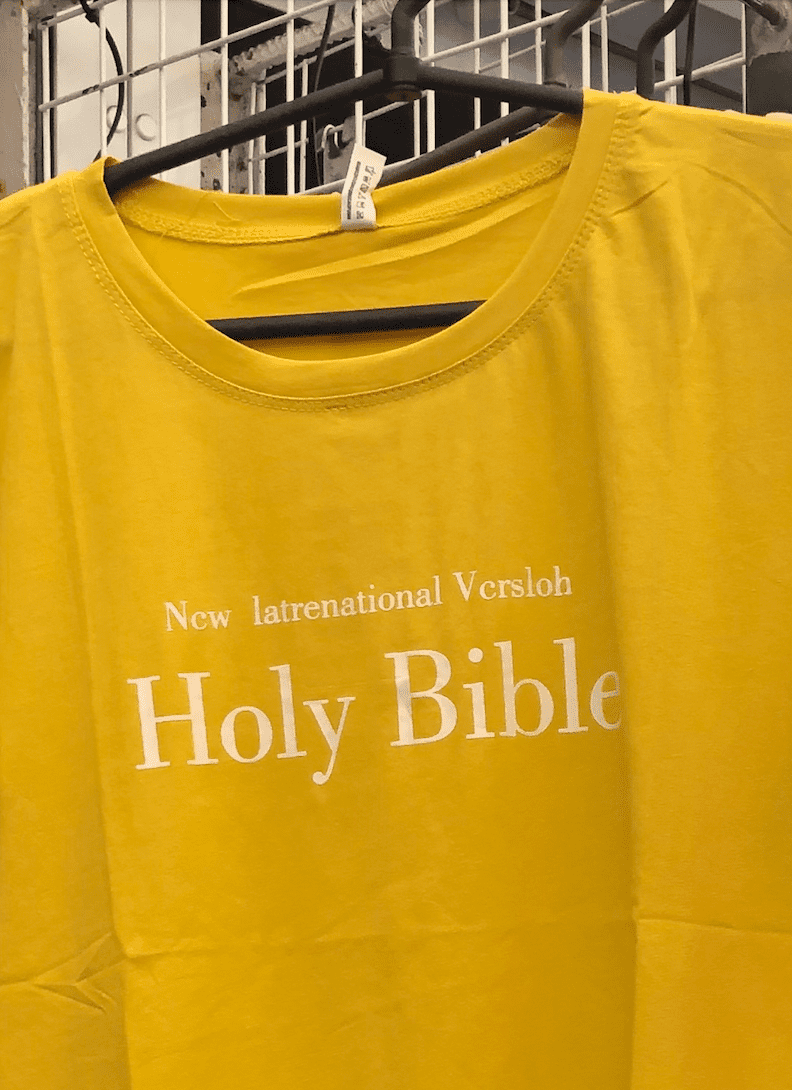

And I got much, much more than I expected: about 90% of clothes on the stalls were Chinese, vine-ripened treasures. They were speaking to you. They were luring you into their world. They were guiding you through it. The cornerstone of the Occident, originally written in Hebrew and Koine Greek, was getting rewritten and sold back to where it came from: the New Iatrenational Versloh of Holy Bible was right there, proliferating before your eyes, speaking the language of shanzhai, the distorted tongues of the Twin Peaks’ red waiting room.

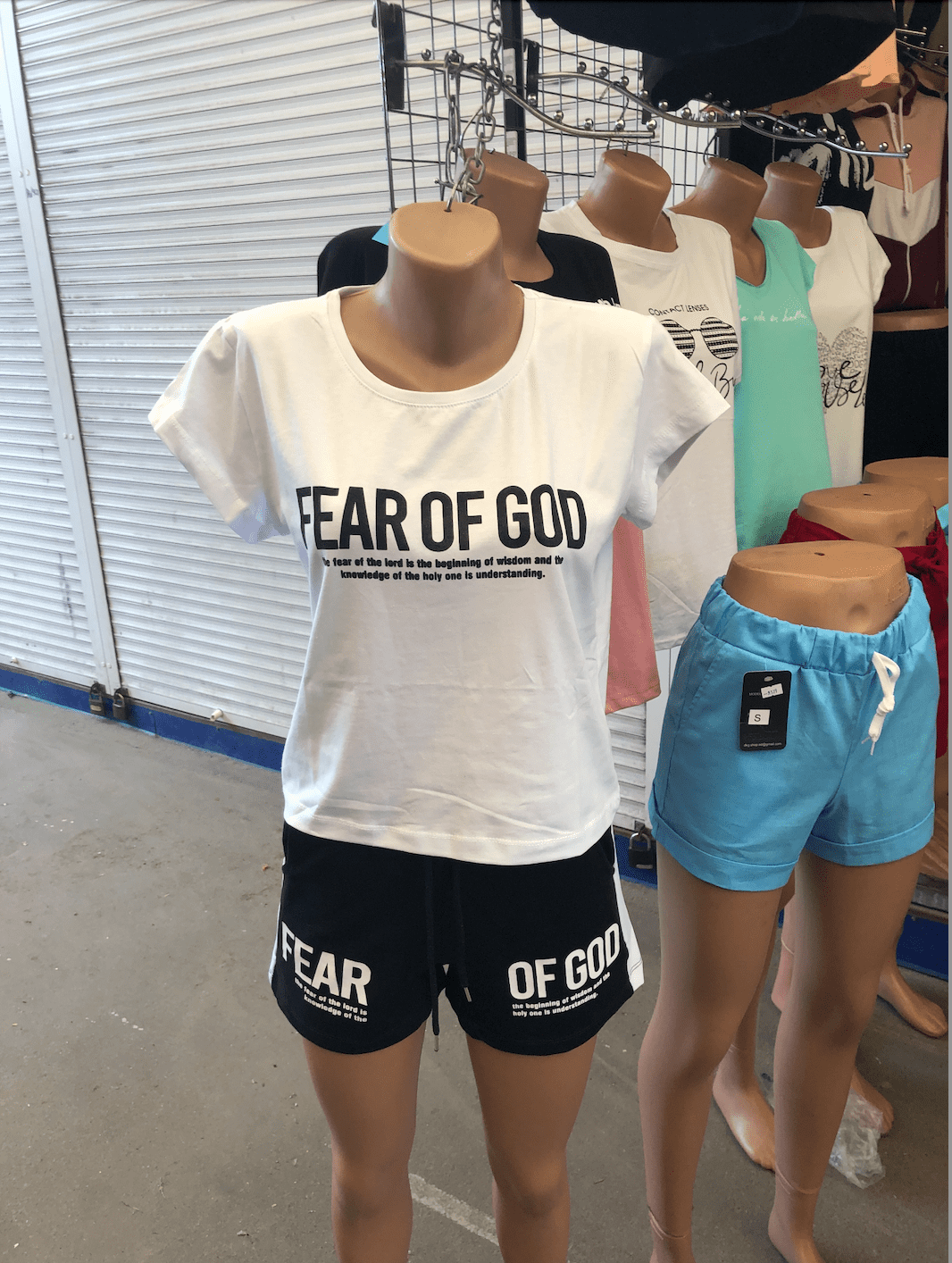

This Versloh instructs you through tees and mini shorts that reveal the most profound truths, straight from Proverbs 9:10 (I acknowledge that I had to Google it to know the source): “The fear of the lord is the beginning of wisdom and the knowledge of the holy one is understanding.”

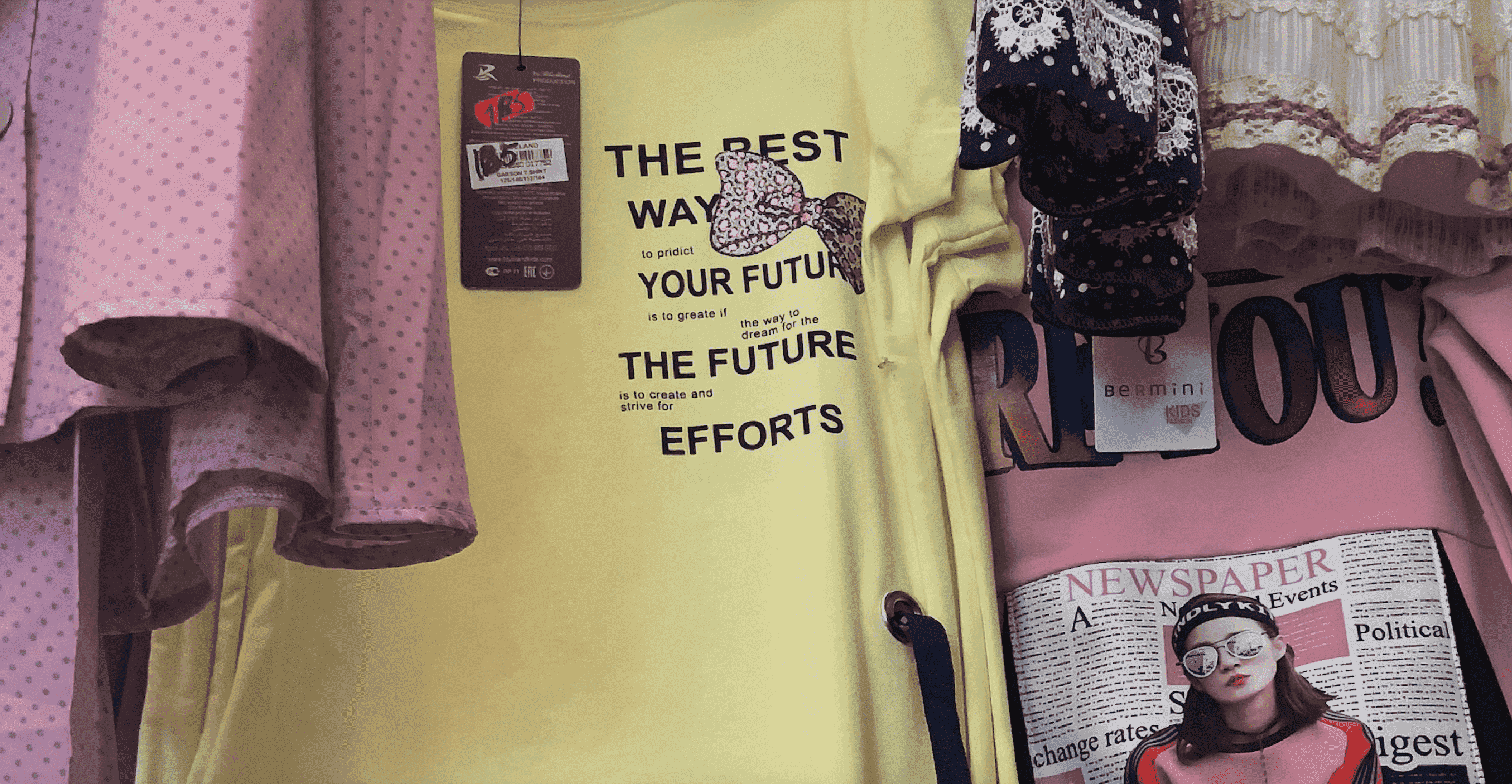

A coy pink leopard bow-knot was decorating a more upbeat, nearly TED talk-esque motivational message:

“THE BEST WAY to pridict YOUR FUTURE is to greate if

the way to dream for the FUTURE is to create and strive for EFFORTS”

Finally, there it was, the dress that started with an empathetic “YOU ARE VERY IMPORTANT TO ME” on the bodice and quickly proceeded to the poorly disguised corporeality of “F K C A ME” drowning in four lines of letters, as if typed by someone playing random accords on the computer keyboard, producing a magic spell, without spaces or semantics.

When I sent a dozen similar pictures to Zairong, we wondered how these phrases could be picked or coined, who were the copywriters behind them. The errors in them are nothing like the machine translation misrenderings or non-native speakers’ experimental constructions. Some look more like typos or even deliberate distortions based on phonetic reading, as in “pridict,” others appear to be letters shifting their identity based on graphic characteristics, when an “i” becomes an “L” and an “n” oscillates between an “a” and an “h.”

Fashion studies scholar Christina H. Moon provides an important comment on shanzhai: “blurring the lines between real and fake, serious or a joke,” these goods “are in actuality born of communal and satirical practices in the production of variations.” Behind the production of shanzhai clothes most often are self-taught women: “On the one hand, her work merges many different elements and features of brands, combining design, labor, and technology together in a singularly creative and unintentional manner, defetishizing and demystifying the privilege and prestige of custom made clothing from the elite class to the working classes by having direct relationships to the factories themselves in which things are made. On the other hand, their work, though labeled entrepreneurial, free, and agentive, is in actuality precarious, temporary, and low waged with long working hours of informal self employment, rife with irregularity and insecurity.” *

What these women are producing is more than clothes. They are responsible for weaving new codes that reveal themselves in serendipitous street encounters, for transmitting messages from the seamy side of the global symbolic order. What makes this process different from glossolalia is its humorous, almost mocking, playful nature that subverts anything that gets canonized, be it Bible or Louis Vuitton. Making its way through multiple dimensions of reality, like the speech that gets warped due to bad WiFi connection or working VPNs during numerous online calls, shanzhai delivers its Twin Peaksian prophecy:

That gUm you liKe is goINg to cOMe baCk in styLe.

* Christina H. Moon, Labor and Creativity in New York’s Global Fashion Industry (New York: Routledge, 2020).