Sign of the Times # 2. The Trajectory of the Family Past

Русская версия / Russian version

"Sign of the Times" is our new series of conversations with Japanese artists who work with the subject of memory and related trauma, touching on the most diverse pages of their country’s history. It is interesting for us to turn to their experience and analyze how different generations of artists interact with the heritage of their country.

The second conversation in this cycle is both a personal story and at the same time a collective story that touched the fate of several tens of thousands of people in the United States and neighboring countries during the Pacific War. This episode, associated with an extreme level of rejection and tragedy, is not so widely known in Russia, although in our context there was a similar story with the Japanese Internment Camps in Siberia. Emergency Decree No. 9066, signed by Roosevelt in early 1942, divided the lives of several generations of Japanese at once into before and after. Many people who were torn away from their native land and dreamed of finding a home in the United States faced the harshest reality and were forcibly placed in Internment Camps that were hastily built in several states at once. Many of these people tried to defend their rights, work and home, someone tried to prove their loyalty and even join the American army, which became possible only towards the end of the military campaign, but most of the attempts were in vain. The wave of racial hatred spread especially strongly, considering that it came not only from below, but also from the top of power. As you will learn from our further conversation, this happened not only in the United States, but also in neighboring countries, Canada and Peru. The lost pieces of life united several generations at once, who, even when this whole story came to an end, continued to fight to proudly admit to themselves and everyone that they belong to several countries at once. Many have lost everything that was in their previous lives, not only in terms of everyday life, but also the feeling of belonging to the country that did this to them, so it took a long time to find their lives anew. Many children not only spent their first years in barracks, but were also born in the Camps, and largely because of this, social movements were subsequently formed that fought for all affected parties to be apologized and compensated. It happened only in 1988, it took a little more than forty years to restore formal justice and make this story visible at the public and state level. But even this problem does not end there, it still requires the attention of researchers and all interested parties.

Evidence of this injustice was also recorded in the art world, especially by those who personally had to go through Camp life, but even after decades there are those who are not indifferent to this story. Today we will talk about the contribution of Aisuke Kondo, an artist who has been researching this topic for almost a decade, referring to the history of his family and those people who were victims of these events. It is more important than ever to keep in mind those stories that took place in the relatively recent past, as they point us to the event pattern and its possible consequences. Aisuke Kondo not only returns to memories of his grandfather, trying to trace his fate, but in a literal, physical way, he is sent back to places that previously served as a place of pain and interrupted time. It is especially important that he also relies on the physical component of memories, which are carried by the artifacts of that time, it is they, together with those places that could already be mastered and begin a different life, that return us to a tangible past and designate a tangle of fates of thousands of people. There is a rational nostalgia in Kondo’s work, without excessive sentimentality, it is accompanied by discussions about where past and present, life and death, reality and memory collide. I sincerely hope that this conversation will be very informative for those who want to know the stories of people who went through these events and get to know Aisuke Kondo’s projects in more detail.

I am sincerely indebted and grateful to Aisuke Kondo for his time for our discussion and for his thoughtful and detailed answers.

Interview with Aisuke Kondo

Gendai Eye: Please tell us, before you began to explore all these layers of information related to the camps and the history of your ancestors, did this topic somehow come up in your family?

Aisuke Kondo: My great-grandfather didn’t tell his family much about his life in an Internment Camp during the Pacific War, so they didn’t know much. He collected arrowheads and pieces of pottery made by Indigenous Americans at the Camp in Utah. Then I only heard that he spent a lot of time there and then ended up in Topaz War Relocation Center. My grandmother knows a bit about my great-grandfather’s 47-year immigrant life in the US, so I heard some of these stories from her. My grandfather was born in the US and moved back to Japan with his great-grandmother, but I didn’t hear much about it from him. And a couple of times I heard about this story from my father.

GE: Apart from the story of your great-grandfather, who had a camp experience, did you have any other reasons to take up this topic? How did it all start?

AK: I became interested in my great-grandfather’s life for the first time eight years after I settled in Berlin. After graduating from the Art University in Berlin, I made a living as an artist but cleaned hotel rooms several times as a part-time job. While I was washing the bath, I found blond hair remaining in a drain. At that moment it seemed to me that my great-grandfather’s life intersected with mine. The fact is that I heard from my grandmother that my great-grandfather worked in a laundry before the war, and after the war as a cleaner. For this reason, it seemed to me as if I had re-lived some part of his life, a very strange feeling. Until then, I believed that I maintained a cosmopolitan view as an artist. And I was also confident about my status as an elite who studied at the University of the Arts in a foreign country, however, I became conscious that I was also an immigrant and therefore a minority. After this episode, I realized that I did not know my history and decided to research the life of my great-grandfather. And I started by researching the detention of people in Internment Camps during the Pacific War. I was shocked to learn the details of all these stories and began full-scale research and creation of works based on this topic in 2013.

GE: How do you conduct your research in the US? How open are the archives and searchable for information, have you ever collaborated with the communities of those Japanese who are engaged in the preservation of these stories?

AK: In the United States, I stayed mainly in San Francisco for three months with the support of the Asian Cultural Council in 2017 and with the support of the Agency for Cultural Affairs for one year in 2018. I have done research in collaboration with many Japanese American communities. I had to learn a lot from my friends, Japanese American artists, and researchers. In the National Archives in San Francisco, I was able to see records of my great-grandfather, great-grandmother, and grandfather. In addition, there are websites that archive information about immigrants, which is how I got information about my family. During my stay in 2018, I was enrolled as a visiting scholar in the Asian American Studies program at San Francisco State University to deeply research the history of Japanese Americans. I also visited a museum that introduces the history of Japanese Americans. There is also information about the Camps and artworks created in Camps. Access to these stories and sites where the Camps were located is open since the US government officially apologized in 1988 for sending people to Internment Camps, and also paid compensation to those who were detained.

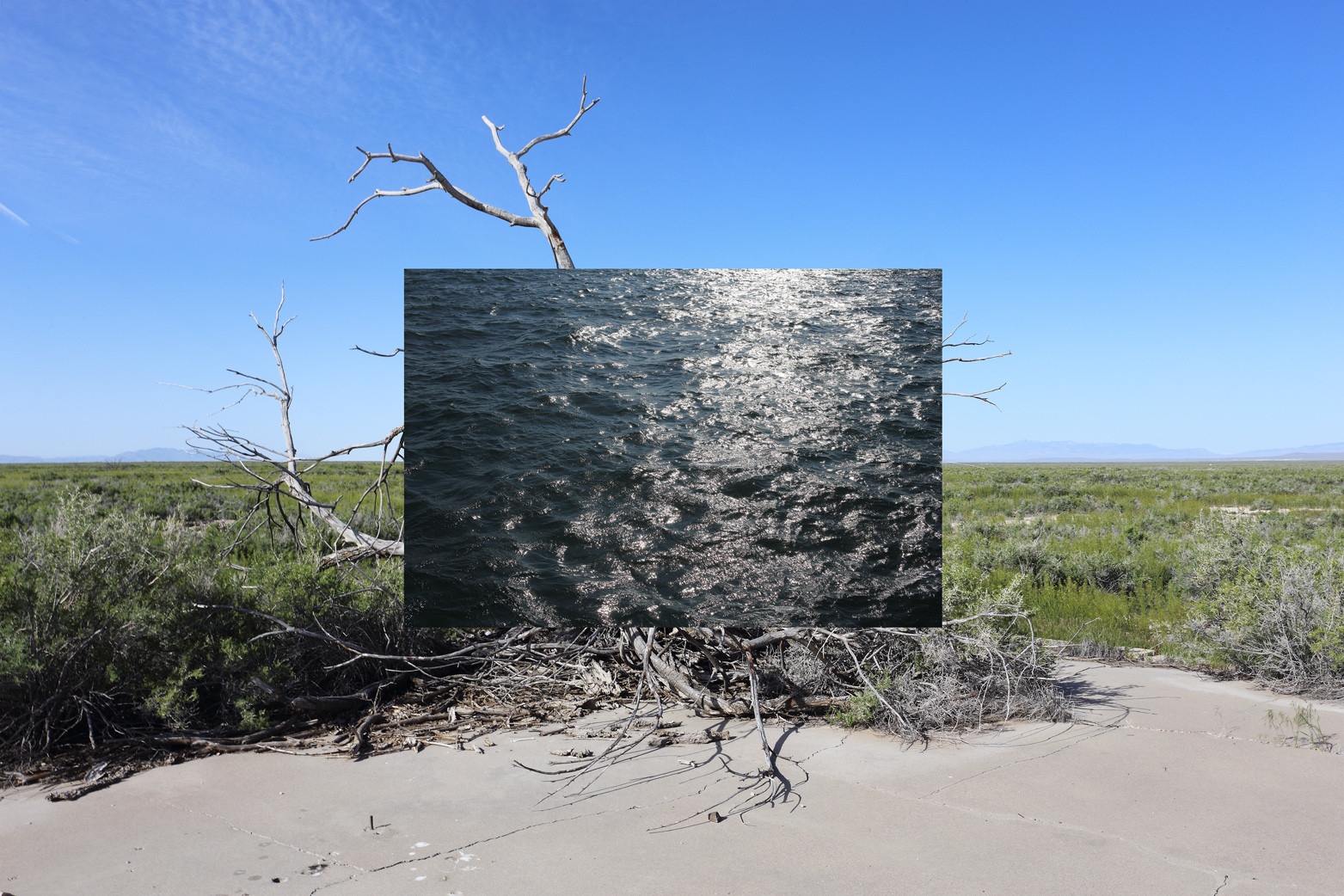

GE: What is it like to feel that some places have already been inhabited and there are completely different buildings, but somewhere there are still endless wastelands and nothing for miles around?

AK: The Internment Camp where my great-grandfather was placed is about 3 hour’s drive from Salt Lake City, and the surrounding area is still like a wilderness. From 1942 to 1945, a total of more than 11,000 Japanese Americans lived there. Temperature fluctuations can be very significant, there are sandstorms, and the earth is dry and cracked. I visited this place in 2017 and 2019. During the first visit, the weather was terrible and the ground turned into a muddy mess due to rain. It was difficult to walk in places, and I wondered if it was really possible to live in such a place. Only indescribable sadness and anger came from my heart. On the second trip, it was very dry and constantly thirsty, the sandstorm was terrible. That was the first time I saw scorpions.

GE: I was also struck at the time that many Japanese were transferred to a camp not only in the United States or neighboring Canada, where, as I understood the attitude and situation were even worse, but also countries such as Peru extradited Japanese citizens to the United States. How wide was the range of these tragic events?

AK: Over 21,000 Japanese Canadians were living on the West Coast in Canada at that time, who were deported from there and sent to Internment Camps in Canada. Japanese who lived in South America were sent to Detention Camps in the U.S.A. most of them were from Peru, about 1800 people. As for the 150,000 Japanese Americans who lived in Hawaii, there was a plan to send them to the Camps, but by then, they made up about 40 percent of the total population of Hawaii, and this was already an economic issue. For political reasons, more than 2,000 people were sent to Detention Camps in Hawaii and Camps on the US mainland.

“About M K” (2017). Courtesy: Aisuke Kondo

GE: In your video “About M K” it also becomes known that your grandfather was sent to war in China as a result of student mobilization and spent two years there. Have you somehow researched this history of your family and what was the fate of your grandfather after the end of the war?

AK: My great-grandfather brought back most of the photographs, letters, and important documents of the American era to Japan. Among them was a letter to and from my grandfather, who grew up in Japan from an early age and was drafted as a college student at the time. I’ve heard he was in a railroad security unit. My grandfather rarely talked about his military experience. There was a telegram from July 1946 left by my grandfather to my great-grandfather, so it may have taken some time for him to reach Japan after the war. After the war, he was informed by letter that the United States had revoked his American citizenship.

I think it was unavoidable that my grandfather was stripped of American citizenship by the U.S. government because he went to the battlefield as a Japanese soldier. If he had maintained American citizenship after the war, he might have returned to America, where his great-grandfather lived at the time, so I wouldn’t exist. I don’t feel resentful about the confinement of my great-grandfather, but I’m angry at that fact. It was not just the American government at the time, but the racism that society has. At the same time, I feel anger at the Japanese government. This is because, even though 120,000 Japanese Americans lived on the West Coast at that time, the Japanese government attacked Pearl Harbor, and it became a cause of the beginning of the Pacific War. It means that the Japanese government abandoned Japanese Americans. And the main point of my anger is against the “war” itself, which always creates dire situations.

GE: The camp experience formed the basis of the work of many artists and photographers who went through them. I especially remember Henry Sugimoto, Chiura Obata, Mine Okubo, Toyo Miyatake, as well as a number of drawings and handicrafts made by ordinary people, the art of gaman. However, there were those who escaped a similar fate and took a prominent place in anti-propaganda art, like Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Ishigaki Eitaro. Where did Isamu Noguchi fit in all this? Again with a reference to your joint artist project with Taro Furukata.

AK: A collaborative project with Taro Furukata in 2016 focused on Isamu Noguchi’s unrealized plan to build a memorial at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Isamu Noguchi lived in New York at the start of the Pacific War and was not sent to the Camp. By that time, he was already a well-known artist, and he had a desire to conduct a public art project for the internees at the Poston War Relocation Center, which was located in Arizona. He asked the United States government to intern him at a camp. After spending about four months there, the project never came to fruition, and it looks like he had to put in a lot of effort to get out of this Camp.

GE: How important is it for your relatives, how do they feel about your project?

AK: I think that my relatives are looking forward to the results of my project. It was important for me to learn the history of my family and see how the wars of the past destroyed the daily lives of people, and how those living abroad had to rethink themselves. I was very interested in the history of my great-grandfather.

GE: And what can you tell about the phenomenon of post-camp silence, when any evidence and experience of what has been experienced is usually hushed up and hidden until the heirs themselves find some things?

AK: As for the history of the detention of 120,000 Japanese Americans, the US government at the time didn’t have a ban on discussing this topic. After the war, many Japanese Americans, first and second generations (Issei and Nisei), spoke little of their Camp experiences. However, about the Internment of Japanese Peruvians and several issues, enough time passed before these facts became public knowledge. By the 1960s, the third generation (Sansei) became actively involved in the student movement and gradually started a public campaign aimed at revising history and demanding compensation.

“The Past in the Present in SF” (2017). Courtesy: Aisuke Kondo

GE: Don’t you think that these events: the destruction of the usual way of life, staying in the Internment Camp, and trying to get back on their feet after it — took years of life from those who dreamed of building their lives in the United States and even being useful for this state. How long did the stigmatization of people last after the camp experience?

AK: I was told that after the war the level of discrimination was very high. For this reason, many Japanese Americans tried to assimilate into American society, to become a “Model minority”. The word stigma is very difficult. It is different between the first generation (Issei), a Japanese, and second generation (Nisei), an American, and I think it will change considerably depending on what perspective you see it. On the social side, it was a big event that the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was enacted by the compensation movement from the 1970s and paid $ 20,000 in compensation to former inmates.

It is difficult for me to elaborate on this as I didn’t grow up in this society, but the experience of internment was associated not only with the loss of work and property but also with identity, dignity, and freedom. I think it was a negative legacy that a lot of people didn’t want to talk about because they were robbed, in every way. At least for my great-grandfather, it was a humiliating experience when he traveled to the United States as an immigrant dreaming of success and was deprived of his self-dignity and freedom by detention. I think that the detention of Japanese Americans has a strong aspect of racist reasons, so I may have felt embarrassed to talk about it.

GE: What would you say to those who are saying: “well, maybe not all of the Japanese were dangerous, but they could be dangerous at some point”? How do you feel about this “possibility”, which most often creates all these troubles and causes suffering?

AK: Even on the West Coast at the time, there were far more German Americans and Italian Americans than there were Japanese Americans. However, in the case of Japanese emigrants, if they had any roots in Japan, they were kept in 10 Internment Camps throughout the United States. It follows that there is a strong racist aspect behind the detentions of Japanese Americans. First of all, because of what was seen as an Asian threat to the United States from the second half of the 19th century to the first half of the 20th century. The “yellow peril” theory was constantly fueled, there were movements advocating the extermination of immigrants from Asia, and some restrictive laws were introduced against Chinese and Japanese immigrants.

GE: In your opinion, is it possible to somehow combine the camp experience and the stories of the Japanese in the USA and Siberia, the Koreans and the Chinese in Japan, just to talk about how war is always destructive for all parties involved? Or will the different nature of the circumstances not make this conversation possible?

AK: War destroys everything and leaves wounds in the hearts of people for generations to come. And I think that the number one reason for this “destruction” is the wrong decisions of the stupid authorities, accompanied by the idea of imperialism and racism. Once upon a time, Japan invaded and colonized other peoples through its imperialism, inflicting unhealed wounds on people. And the racism was from the United States, which put Japanese Americans in Camps and thoughtlessly dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And even now, in 2022, there is still destruction and war in this world, and this hurts my heart very much.

GE: While working on this project and discovering this topic, have you begun to wonder what it means to you to be Japanese? What role does nationality play in the present?

AK: Ethnic and national identities are very complex, and while researching Japanese-American history, I feel that Japanese-Americans have always been swaying between these two identities. And I think we must always consider the fact that they are easy to use in politics. For example, what is Japanese? In response to the question, I think that there is nothing but the meaning of nationality in the present society, but people tend to want more spiritual attribution, and sometimes politicians try to manipulate that emotion of people.

GE: What is our common responsibility to preserve the personal histories of those who went through the hardest trials caused by the course of history and war? What is the place of memory and communication between generations?

AK: When we learn history, we tend to only focus on a main story which is normally passed down by the majority. However, in that story, surely the daily lives of countless people are included. And at the same time, the daily lives of countless people have been destroyed by numerous wars. We must not forget that there are numerous personal stories in history. If we lose that perspective, I think people start to modify history and believe in their convenient history. I think it is really important to inherit and preserve personal history.

“here where you stood” (2017). Courtesy: Aisuke Kondo