mobile crematoriums

версия на русском

mobile crematoriums

mothers giving birth in basements

open burial pits

death from starvation and dehydration in besieged Mariupol

blocked humanitarian corridors

shelling of evacuees

deliberately destroyed residential areas

officials who lie about dead conscript soldiers

stampede and panic at the borders

provocations in Donetsk fabricated by the military

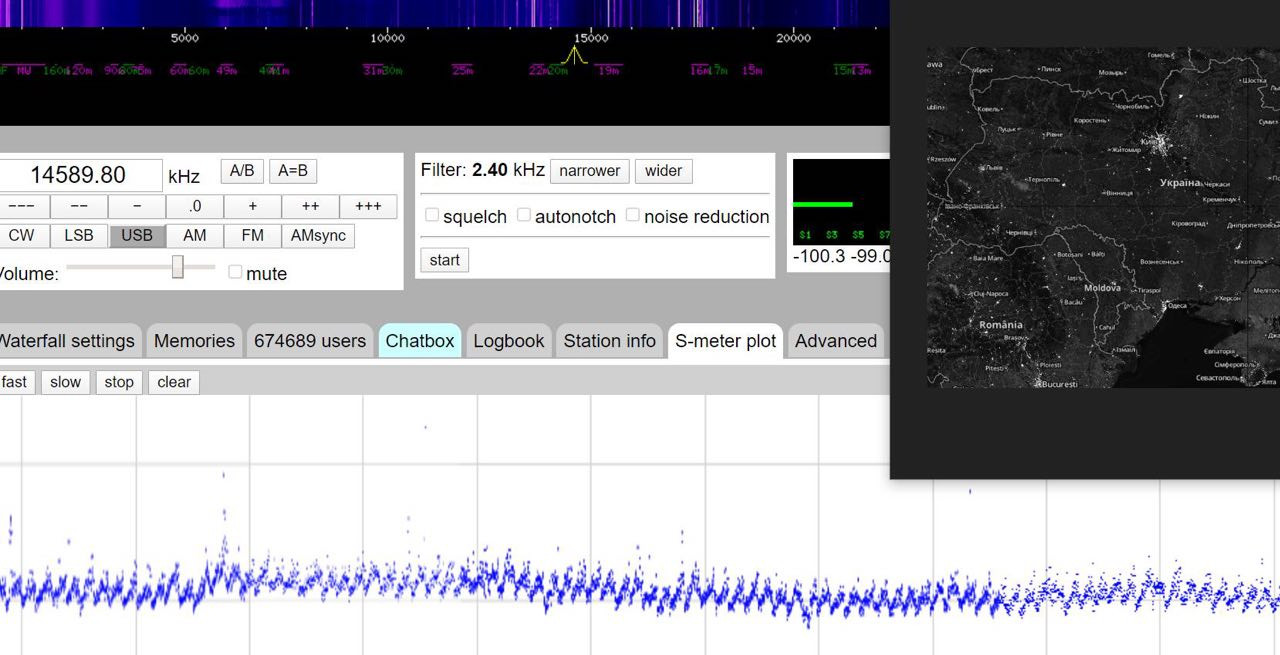

over-regulated Internet

refusal to return dead bodies to their homes

war crimes committed with cluster and vacuum bombs

playing with nuclear threats — the grin of madness and powerlessness

How did this even become possible? During the years of Putin’s regime the political space has been narrowed by repressions, total censorship and the military-style rule exercised by the security apparatus. The entire opposition has been liquidated by contract killers shooting in plain sight, political persecution, trumped-up criminal cases and imprisonment of activists.

Currently, any opinion that differs from the official view of the state amounts to treason and is punishable by fines and imprisonment for up to 15 years. In order to be prosecuted, it is sufficient to draw a “NO WAR” banner or post a tweet.

In the first week of the war, the Russian censoring agent Roskomnadzor shut down almost all opposition media outlets. Аfter a series of searches, direct threats, pressure and arrests their employees were forced to leave the country. Many independent media have suspended their work because their right to public speech has been crippled. Students are expelled from the universities and employees are illegally fired for articulating an anti-war position.

For those who have left Russia and continue to talk about the war and cover the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Armed Forces, it will be impossible to return home under Putin’s current government. Certainly this is not the first mass exodus from the country during his rule, but probably the last and devastating one.

I am writing about this while in Georgia with my 12-year-old son, where we stay in limbo between the impossibility of returning back and the lack of prospects for the present. This position allows me to write from a safe place. Same cannot be said about the people of Ukrainian cities, those who shudder at explosions, refugees waiting their turn at the border or the morally and physically repressed activists in Russia — all those who for various reasons needed but haven’t been able to leave.

I want to think that the invasion of Ukraine by Russian Armed Forces, mass repressions in Belarus, bloody suppression of the protests in Kazakhstan are the final convulsions of the outdated clinical patriarchal politics, which will soon become impossible.

Veneration of dictatorship and Tsarism ingrained in the minds of the Russian majority cannot exist in modern society. Nowadays it is not enough to shut down the radio station “Ekho Moskvy” and think that one controls the mindset of the country. Digital capabilities are precisely the capabilities rather than means of control. If we use them strategically, we all have the capacity to organize and mobilize resistance.

Passivity, hegemony, universalism and authoritarianism are not our only problems, of course. The reactions of a number of NATO countries and the US also leave a lot to be desired; it repeats the same outdated scoreline: mutual deterrence and subsequent payoff.

If feminist politicians dominated the field of public policy, the majority would not think in terms of the conflicting interests of states. Imperialism, war crimes, fascism and discriminatory logic would be directly criticised. (By the way, what is the strange coincidence that so many captive soldiers of the Russian Armed Forces turn out to be from the peripheral Russian geographies, from sub-proletariat classes but not from wealthy families of Moscow or St.Petersburg?) Why are we now pinning the hope of resistance on the women’s mobilization against the conscription of their children into the army? Because it is the mothers who are aware of the reproductive care work and social responsibility. The latter are of no value to the Russian state apparatus with its low social security provision and shimmering health care.

For the Russian extractivist war machine, nineteen-year-old children from the periphery are just another kind of resource for maintaining colonial authority, so that the Russian government can further back other oppressive regimes in Belarus, Kazakhstan and Syria. Providing social securities or life prospects is not important for the regime which foments pseudo-patriotism in schools and suppresses the individual’s ability to criticize and question.

Russia’s contemporary imperialism became possible through perpetuation of political irresponsibility and normalization of violence against the racialised subjects, migrant laborers, political and LGBTQI activists. Nothing will change without changing education policies and the parameters of access to knowledge and public speech. We need institutions to develop political subjectivity from an early age.

Today we see borders of states being redrawn before our eyes: by missile strikes, blown up bridges, captured infrastructures. The borderlines are bleeding. Bodies mutilated by explosions manifest these borderlines. The wounds left on the body of earth by the funeral ditches and forcibly occupied territories will be turned by the authorities into shining pictures of recent history in school textbooks. No one shall learn to live with the pain of war and to become patient about their grief. So, the stories of war must be retold in tongues of fear, despair, impossibility and sorrow. The patriarchal optics is to blame for glorification and aestheticization of war narratives.