Mia Donovan: Recovery Folklore

Mia Donovan is a filmmaker based in Montreal. Her films INSIDE LARA ROXX (2011) and DEPROGRAMMED (2015) have been presented worldwide at film festivals, on TV, distributed theatrically and via Netflix. In 2012 she was the recipient of Don Haig Award and in 2016 IDFA DocLab Award for Digital Storytelling.

_

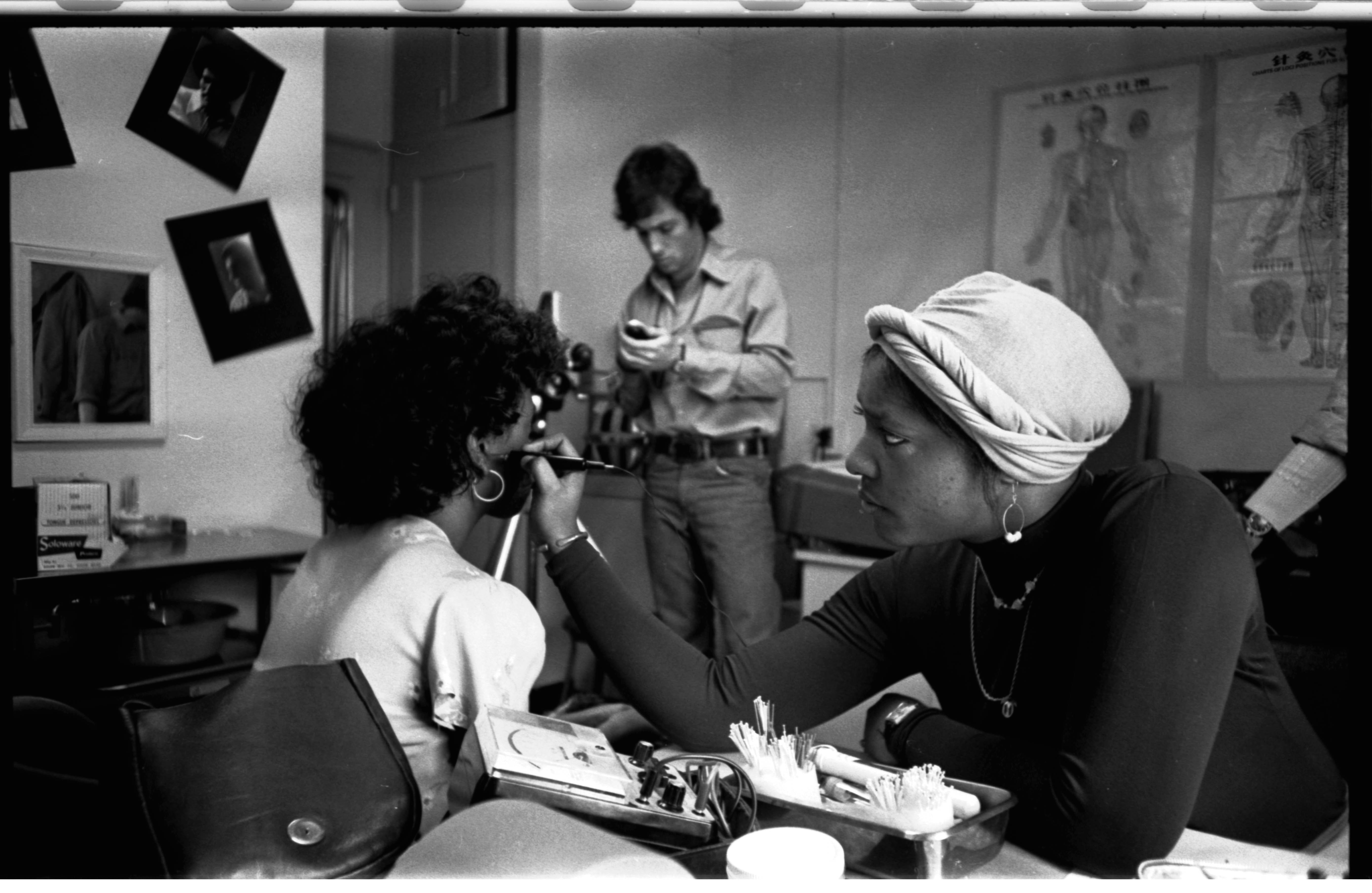

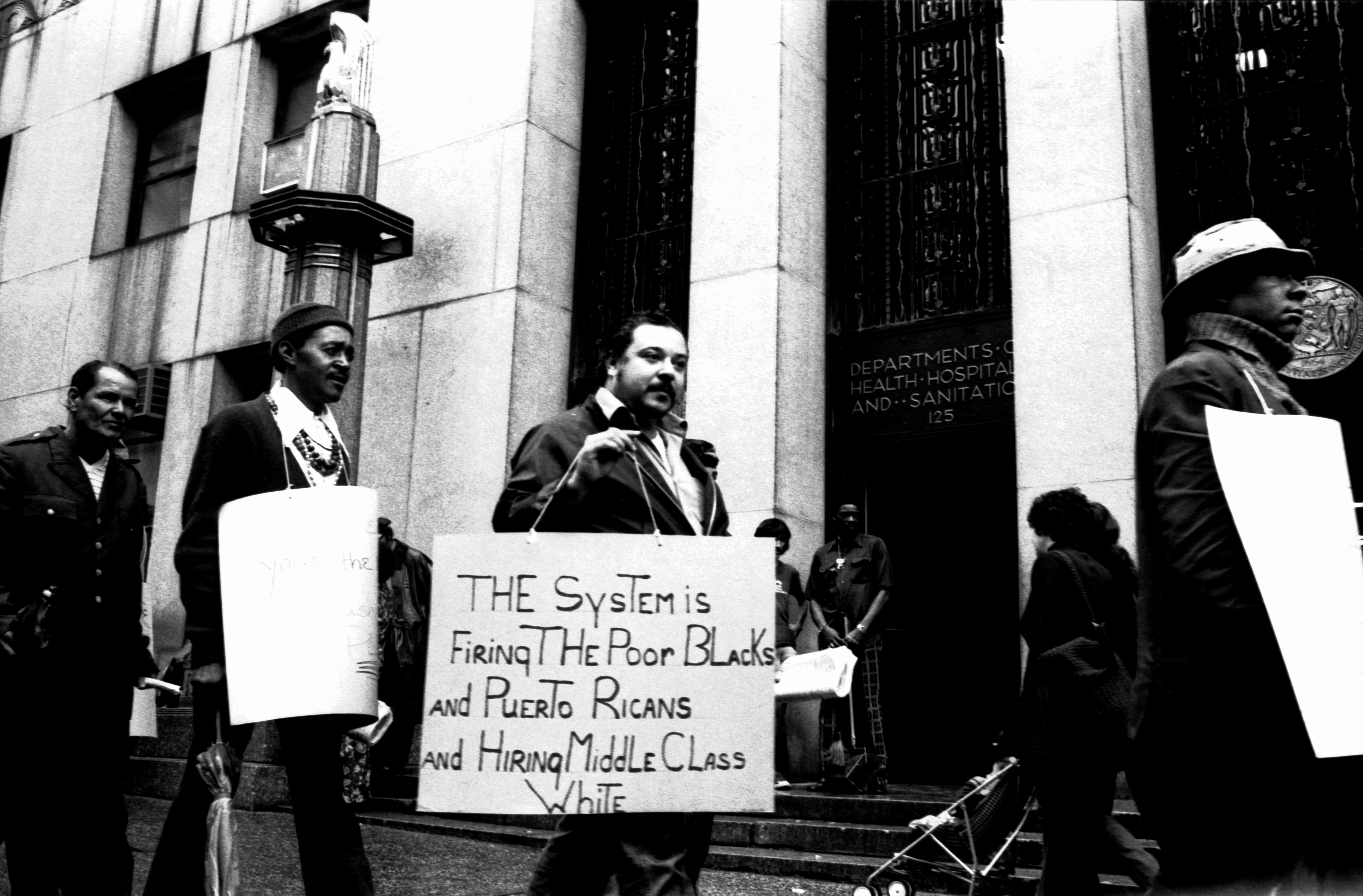

Berlin 7 PM- Montreal 1PM, Skype on desktop, interview conducted by Anastasia Kolas, from Issue 3—Hyggelig—Winter 2020 (Archive), all images: Carlos Ortiz

N: You are currently in production for DOPE IS DEATH (2020), your latest feature documentary on the history of the acupuncture clinic and addiction recovery center run by activists such as Black Panthers and Young Lords, in South Bronx in the 70’s. How are the finishing touches coming along?

M: It’s been a challenging project. I am dealing with history, or with a historical story, that hasn’t been told properly. And I am also trying to weave into it present day material, like some cinema verité with people who practice acupuncture protocol that they had developed. I’m also dealing with politically sensitive topics. One of the characters is a political prisoner, so it took a long time to get access to the right people, to have their trust, find things in archives. It was hard to grasp, or it was a lot of trial and error when trying to tell the story.

N: Was it trial and error with building the narrative, or trial and error related to the gathering of information, or to figuring out the level of involvement of the participants?

M: It’s been trial and error in that there’s been a few different editors I worked with. I wrote this film as a research project, and there are different ways to do a documentary. Some people will research and will say: this is my thesis, I’m going to interview these people, I know what they are going to say. But this project, I didn’t know what it will be. It hasn’t really been written about before, I didn’t know a lot of the content of the story. And I wanted it to be told from a first person point of view. So each person I would interview, and in a sense collaborated with, would steer the film in a new direction. Sometimes the editors will take footage and would just want to build cool scenes. And maybe that’s what you have in your heart or your mind, but it isn’t really in the footage and we have to get there, you know. I ended up editing it myself and having people come in at this late stage to finish, but it’s been really hard to find the right collaborators.

N: It can be. And you’re working with so much material.

M: Every project’s different, you know, but this project’s been very challenging. I think I learned a lot from the last two films that I didn’t want to repeat. Like compromising a little bit and then seeing it on the big screen and thinking I should’ve aired out this project more, I should have had more time to sit back and reflect on it. And then go back to finish it, instead of feeling rushed. So this time I was just really refusing to rush it and showing it to the right people for feedback. Because it’s a story centered around people who lived through the civil rights era, I’m learning from them. So I needed them to watch it and give me feedback.

N: Yeah that makes sense. So the reason why I wanted to talk to you is because this issue of the journal is called Hyggelig (in Swedish). It refers to cosy, comfortable or traditional, and I really wanted to take apart what that means. I have lived in Canada for the past year and was at a post office around Holidays and the stamps said Merry Christmas. There was no other option for stamps, which is odd because I would think this would not be happening in Canada. So I wanted to talk about comfort, in many ways. Your work a lot of the time I think it has to do with recovery, or various forms of recovery. Not necessarily about arriving at a sort of closure through the recovery, but about looking at situations that require recovery and how they happen, and at those who are in recovery or provide a recovery service. And it’s about whatever we call “alternative” recovery methods. In this case specifically, what you are working on is so interesting, because the film brings together the history of the civil rights movement and acupuncture.

M: Yeah, my work is about recovery and radical politics. Or — and revolution.

N: What happened since the last time we talked about the film? I think you were coming to New York to do some initial shooting, right? And then I moved out of New York and so I haven’t really talked to you about it after that.

M: That’s true that every time I’d been to New York recently, it has been to shoot, and every time I had about three interviews lined up. At first everybody approaches me with suspicion, and then… If people are on board, every single time they say, ok I’m gonna give you the number of this other person. So the film had grown that way. A lot of people I ended up interviewing I didn’t even know existed before I started shooting the core characters. It’s just this history that has received some, but not a lot of, attention. If you google "acupuncture to treat addiction" you will find out about a clinic founded in 1985 by Dr. Michael Smith from South Bronx, who is a white doctor, who sort of started this National Acupuncture Detox Association. And most people just think that’s the roots. In reality, the history of acupuncture to treat addiction started in 1970, with activists — Black Panthers, Young Lords. Dr. Michael Smith was there because they did it in a hospital in the South Bronx, and they needed a medical doctor to oversee the program. But then, because they were doing political education classes in addition to detoxing from heroin, they got red flagged and they got eventually shut down. Chuck Schumer, who was an assemblyman in the 70’s said that it was a rip-off drug treatment program that was indoctrinating political radicals, and that they had links to domestic terrorism, because of Black Liberation Movement. So they were shut down. And then a lot of the activists went on to become more militant in their activism, some got tied up in the 1981 Brink Armored Truck Robbery in Nanuet, NY. And a lot of them are in prison. So they have been labeled as criminals, and are not included in the proper history of acupuncture to treat addiction, or given the credit.

N: So everything’s been conflated into one thing, and only this doctor, was left to represent the whole history of it.

M: Yeah so the documentary is telling an untold story. And… it’s not just: here is the real story. It’s more like: this is the story. People modeled themselves after the Barefoot doctors in China because people of colour, and poor people didn’t have the same access to medical care in New York as others with money. So at the clinic they were teaching people so that they could provide basic healthcare to their respective community. Then they started detoxing addicts and then went on to learn more about full body acupuncture. The film is really about this movement and about those who brought acupuncture to the US, and made it into a legal practice without a need for a medical license. Before 91' you had to be a doctor to perform acupuncture. The people who started it: Mutulu Shakur, Walter Bosque and their students, were the ones who started the first western acupuncture school in the US.

N: Mhm, interesting, so… What you’re saying is, you had to be a western MD with a degree to practice acupuncture?

M: Until 1991 in New York, until 88’ in California, and 84’ in Quebec, you couldn’t practice acupuncture unless you worked under the direct supervision of a medical doctor, a western-trained MD. Acupuncture was considered an experimental treatment and it had to be done in a hospital. People did practice acupuncture in clinics, but they were getting raided by the police. There were of course acupuncturists in New York City, but we are not talking about Chinatown, because Chinatown is different. We are talking about western acupuncture.

N: So the New York’s Chinatown practitioners were able to offer acupuncture without MD supervision, even prior to the legal changes of 91’?…

M:… yeah the difference would be that it was really hard to learn acupuncture as a westerner, because you know the way that you would learn… I’ll just go to this a little separate subject.

First time acupuncture was introduced to the West was through a man called Jean Soulier de Morant, a Frenchman who grew up with Chinese nannies and who in the 20’s he went to Shanghai. He could speak the language and became obsessed with acupuncture. He translated all these acupuncture texts to French. The original Chinese text would say something like “the meeting of two dynasties” (points to chest), and he would call it — Lung I, you know. So he would translate the points into the language of Western anatomy too, so that Westerners could understand it. That took him 22 years. And then he brought it back to Paris. De Moran, who was also an amateur boxer coach, trained Oscar Wexu, a Romanian-Jewish boxer. He said to Oscar one day: you have the hands of a healer, you should become trained in this. Oscar learned Chinese massage and acupuncture, and brought it to Montreal in the 50ies. But he only practiced Chinese massage in public, not acupuncture, because he didn’t want to be shut down. Then in the 60’s, Mario, Oscar’s son, was doing massage with his dad for these lumberjacks, who were Jesuits, and Jesuits knew about Chinese healing practices. So they were sending lumberjacks to get Chinese massage. And Mario was like — Dad, can we just do acupuncture for his asthma, it’s gonna help him… So they started to secretly do it. And it just grew, people kept coming. This was during the Revolution Tranquille in Quebec, so people started to question the authority of the church and the medical system, so it became very popular here. Meanwhile in South Bronx they were trying to find a non-chemical solution to heroin and methadone. The Black Panthers and the Young Lords felt that both methadone and heroin were being used as part of a chemical warfare to pacify black and brown resistance. So they were really opposed to methadone. And they heard about acupuncture, about Montreal, that there was a school here, and they came up and learned acupuncture. They got back to New York, and the minute they stopped administering methadone at the clinic, they started to get monitored by the city, and eventually got shut down.

N: The Bronx clinic started getting monitored because they were not administering methadone?

M: Well. that’s what people say but we don’t know for sure. But also in conjunction with the fact that they were political… Or organizing people politically.

N: What is the current state of or lawsuits, or the results of the legal proceedings that happened with the people who led this clinic?

M: This is going back to 1978, there’s not really any lawsuits per se directly related to the clinic, the clinic was just shut down. But the clinic was shut down on the grounds that they were mismanaging funds, that they were not practicing real legitimate medicine. In the eyes of Health and Hospital corporation of New York that would be methadone and more traditional aftercare programs. The clinic did have an aftercare program: political education classes. They were going against the system and the city wanted them out. They blamed it on billing, mismanagement of funds, you know. It was said the clinic was defrauding the city. They were accused of all this stuff and shut down, but nothing happened. There was no lawsuits, no one was charged with fraud. Yeah… so, people just went on, and did their own thing after that.

N: What did the aftercare looked like before the change to acupuncture, like whats’ the traditional aftercare program?

M: There really wasn’t at the time, everything was new. In the 1970's, in the eyes of the city it was probably like: you go, you get your methadone, and you go to see a counselor who helps to get your life together…

N: … so therapy of some sorts…

M: It would be kind of more like AA type of thing. But the people who run the clinic were opposed to AA, they opposed it for the same reason they opposed methadone, because the framework of AA it’s all in the “I”, like “I have to take responsibility for my life”, but their framework was like, it’s the system, it’s the society that’s making us addicts. They don’t want us, they want us to be pacified, they don’t want us to take over. They don’t want us to revolt, they want to keep us here. They want to keep us poor, they want to keep us misfits, they want to make us criminals. So that was their outlook. They were going against all the research that was growing about addiction at that time, you know. The methadone maintenance was the standard. But the Bronx clinic wanted methadone detox: they wanted people off of all of the drugs, they didn’t want to replace one drug with another. There was this idea that heroin addiction wasn’t treatable, or there was no cure, and they said — they were — the cure.

N: And not to tell all of the upcoming film, I want to ask: how do you feel about the film now, besides the anxiety of editing, is it giving you thoughts for your next work?

M: I am doing something completely different for the next film. It’s a narrative doc, called THE TOUCH OF HER FLESH, about stripping. It’s about aging in a hypersexualized environment and in the wake of #metoo movement. The characters are: one very young woman, maybe 19, one in her 30’s and one 40+, and it will be about how they navigate their life, this world, and aging.

N: What does it mean when we say here: a narrative documentary?

M: It’s a good question because it’s different for everybody, there’s lots of different ways to fit into that category. Some people call it hybrid doc. There’s different ways to approach it and all these different terminologies for it. There’s a few films I really admire, that use this approach. One is called The Rider By Chloe Zhao, it’s a film about rodeo riders, cowboys at rodeo shows. She cast a real family of rodeo guys. Some of them had been injured… She sort of worked with them on a script where they’re basically telling their own story. But she writes it like they are acting, she shoots it like fiction, but on set they are playing themselves.

N: A re-ёnactment?

M: Yeah. It’s a really beautiful film. For my film too, I am hoping to cast real strippers. I am also opening out to the idea of having actors, but I’ll be shooting in real strip clubs and casting as many real people as I can, like bouncers, doormen, and I will be working closely with the people I cast to write a script in collaboration. I already have a general idea. I won’t shoot it like a documentary, I will shoot it like fiction: rent the club, shut it down, orchestrate or compose every shot, you know.

N: And it will it be set in Montreal? Do you have a specific place in mind?

M: Yeah, it will be in Montreal, I already have some places in mind, like places I spend time in, or used to work in, that I’d want to use. But there’s also so many options. There were like 300 places in Quebec at one point. It’s an industry that was very strong here, in this culture, that is disappearing, for different reasons. It’s still alive but it’s been fading because of the internet. So it will also work as a way of preserving a part of this very Quebec history.

N: It’s a complicated history, right? Because…

M: Quebec was a such a catholic place, you know Quebec was the last province in Canada where women couldn’t vote. Women couldn’t vote here until 1940. But it also had a history before that, before the 50’s when we had 400 Jazz clubs in town, you know where Place des Arts is? That was all jazz clubs, before they built that. All the burlesque! And imagine all the musicians that lived here! It’s kind of crazy. So that was in 30’s and 40’s and then it got more conservative in the 50’s, and then the Revolution Tranquille happened in the 60’s which was really the beginning of Quebec’s stripping culture.

N: But it’s also like a complicated history, because how do women feel about participating in this history? What is the history of that? It’s one thing that it is a historical fact, and then there is liberating and libertine aspects attached to it, but another is of complicated stories. Like I’m thinking it took me a long time to understand from watching it initially as a teenager in Belarus, why Jack Reno in Twin Peaks was based in Quebec, and they kept crossing the border. Until I moved to and lived in Canada, and got to know the history…

M: Yeah. I am also thinking about the #metoo movement here. I have so many friends on Facebook who are from that industry, so many strippers, former strippers, former sex workers, and none of them participated in #metoo movement, none told their stories. And I thought, oh that’s interesting, I wonder what it’s like right now. You know, like, for them. Like how do you explain your position to your friends when you are working in this industry, where you want guys to look at your tits, you know.

N: Yes you do want them to look, but there’s still boundaries. The thing we all want people to “look at our tits”, or to see us as desirable, beautiful beings or whatever, but you know… It’s interesting that it becomes this conundrum, or conflict of interest for some reason, in certain ways of rhetorical categorizing and cultural commentary, if one is a sex worker.

M: Yeah, you know, I always wanted to do something on this subject, and now I am ready to do it.

N: I’m sure it takes time to process your own experience.

M: Now that I am a middle-aged woman, and it’s all behind me (laughs).

N: How do you feel about middle-aged?

M: I kind of grapple with it. I feel like I should feel different but I don’t. I feel like I should enter a new mindset, I am still waiting for that to happen.

N: Because we were talking about all the people you plan work with, and how you are going to hire all these collaborators, like bouncers and so on, and this is for the next film, but even for this film, there’s been so many people you work with on a regular basis. How do you find that as part of the process?

M: …do you mean in terms of the participants?

N: I mean everyone, like there’s crew, and there’s also participants, and then there’s communication, preparation, over email, and so on. It’s a lotta people time, it’s not solitary work.

M: My favorite part is interviewing and meeting people, and talking… And the editing for me is always frustrating. For this film, I had a really hard time editing. I had always, but this film was really hard, I actually had three different editors and they all helped to advance the project. But this is first film where I had to edit myself. I didn’t really know what I was saying and I was trying to find that out through the material. Right now I am working with Sofi Langis, who’s the finishing editor. She’s heard me talk about this project for years, and she’s the first person to collaborate with who, it feels like, is really in my head. She’s really one of those trusted collaborated… In a way I haven’t trusted another editor with this project. Some stories tell themselves, but this one… Every person had their input: people from Puerto Rico Liberation movement, some people are from militant Black Liberation Movement, some are from the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, some are white activists from the 70’s.