Slavs and Tatars: Interview

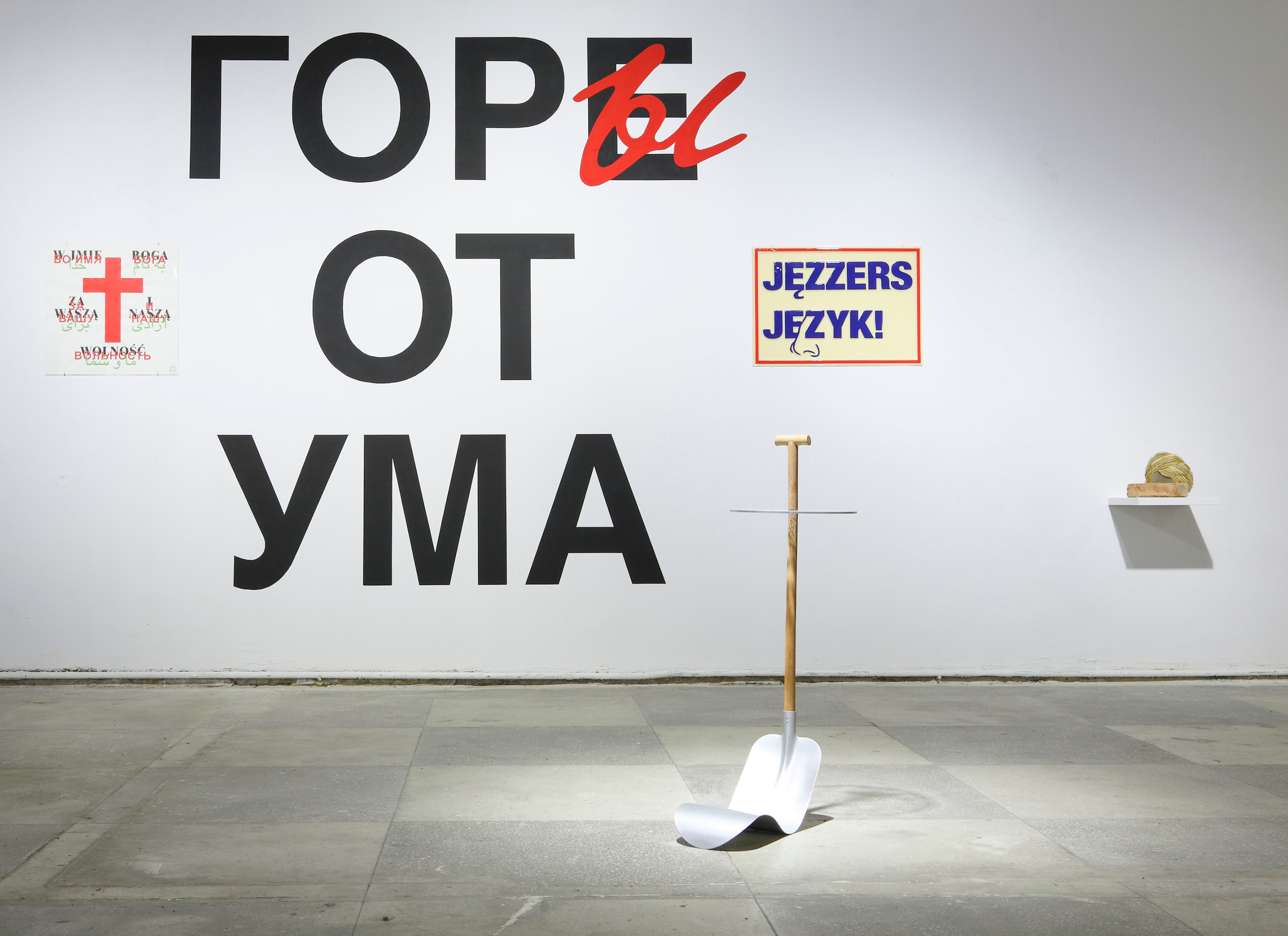

Slavs and Tatars’ exhibition "Movaland" opened at Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art in Minsk on February 21, 2019. Organized with the support of Goethe Institute, the exhibition came on the heels of a residency program for Belarusian artists at Slavs and Tatars’ studio in Berlin. The collective’s work can be divided into three main activities — publishing, exhibitions and lectures, with a focus on the cultural, historical, social and heterogeneous space east of the Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China. We sat down for a talk with one of the members of the group. The day before the opening, Slavs and Tatars presented a lecture “Transliterative Tease”, about phonemes, graphemes, transliteration and how language becomes a political tool.

From Issue 2—Acid Reflux—Summer 2019 (Archive)

The interview was conducted by Katherine Rutkevich and an earlier version in Russian was published in The Village, it was translated for Nacre Journal by Anastasia Kolas with some editorial adjustment by Slavs and Tatars.

Slavs and Tatars started as a book club, please tell me what books you discussed and why?

It started in 2006, and yes, we started by discussing books, for example, Aleksander Herzen’s “My Past and Thoughts”. The choice of books was not accidental. We started Slavs and Tatars books to fill in the holes in our the education. Despite the fact that we had the privilege of studying in great institutions in New York, Paris, London, we realized there were systemic shortages. Take Herzen for example. No one really teaches Herzen. Nobody even knows him outside of Russia. Even in Russia, Herzen is not read right now because during communism it was obligatory reading. But Herzen is arguably the most important memoirist of the last two hundred years. In fact, this is a common problem regardless where you are: in Jakarta in Moscow, in Tehran or in Berlin — the canons are roughly the same. For some reason, it is widely believed that the West is more enlightened, so we need to import the Western system of knowledge everywhere else. Maybe it’s a form of academic laziness? I find it strange. But there are many other sources of knowledge that do not fit this standard.

For example?

For example, take Suhrawardi’s Ishraq, a very sophisticated Islamic philosophy of illumination, of light, as important to the history of philosophy as any of the Greek philosophy. Another item of additional knowledge that we did not find at our universities and in our education is an alternative to secularism. In the West we have come to believe that religion is for commoners, and that we, intellectuals, are somehow above it. Surely, there are other forms of knowledge beyond the rational. Incidentally, this is a very sensitive and urgent issue for contemporary France. Even my close French friends can’t imagine that a person can be an intellectual and at the same time assume that not everything is within the realm of the rational. And furthermore, that the two positions do not need to be in opposition or to exclude one another. There are different forms of knowledge: mystical, metaphysical, affective, digestive. When you read a medieval text (be it Jewish, Christian or Muslim), you can’t just read it in gloves, in a disinterested clinical manner. The text needs to be both analyzed and lived. Few French scholars are capable of this, they habitually look from afar. But the Germans, historically, were more prone to such an approach.

Have you heard of the philosopher Solomon Maimon? Originally from Belarus, he studied various philosophical texts and amongst them the Torah and was known for criticizing Kant.

Of course, I do know him. Exactly, there are more people like that beyond the Western Canon. One of our latest "discoveries" is the philosopher Johann Georg Hamann, a frenemy of Kant. He was an interesting personality. He criticized Kant and the Enlightenment, but used a very particular methodology: a strange brew of Lutheran theology and highly sexualized language. He argued for example that Reason does not exist and is a man-made abstraction. And we asked ourselves: why have we never heard of him? Most educated Germans don’t know about him either. Sometimes such figures challenge you: isn’t that the aim of education, to challenge the foundations of one’s thought?

Then, in 2006, almost simultaneously with the start of Slavs and Tatars as a collective, we realized that if we move in the same direction, we’ll end up in the same dead-end of diminishing returns, insular thought, and a certain cosmopolitan parochialism. We will read Deleuze, Foucault, Agamben, ad nauseum. In the books we publish you will never see these names. Not that we don’t read them. But rather, if we mention names, they should be those outside the canon. It is always important to face what you don’t know. Especially today with the silos of social networks, we are less and less confronted with ideas or thoughts antithetical to our own. But in fact knowledge arises when you encounter the opposite of one’s self.

And then you started publishing books.

We started very modestly. We read and translated what wasn’t available in English. And sometimes we re-published what had been published earlier and since out of print. For example, we found a small 1933 Soviet Academia edition of Safar-name (Travel Book), written by poet and philosopher Naser Khosrow. It contained 10th century miniature maps from the Middle East made by Abu al-Istakhri. They had nothing to do with the text of Naser Khosrow. And we published these cartographies and translated the legends text that accompanied the maps for Baghdad, Baku, or the Persian Gulf.

And at what point did you come to consider yourself as artists?

Initially we had no intention of becoming an art collective. Everything we did in the first three years was on paper. If people wanted to see our work, they had no choice but to read. The first time we successfully worked with 3-dimensional space was our contribution to the 10th Sharjah Biennale in 2011. In retrospect, perhaps one of the reasons for the success of that project was the following: when the public comes to our exhibitions, they don’t have a sense of being spoken at, talked down to or a hierarchy of knowledge, despite the extensive research and discourse present. Very much akin to a book club, we are sharing our research and interests and hope others can join in the particular pursuit. Yesterday, after the lecture, two people approached me, Sergey Kharevsky and his colleague Hussein Nailevich, they are more knowledgeable on the topic of Tatars in Belarus than we could ever dream of and we look forward to corresponding with them in the future.

So the audience or listeners become equal participants.

Often in art, people concentrate on representing what is close and familiar to them. From the very start we decided that we would focus on those things we don’t agree with, or don’t understand. Unlike in science, in art it is quite rare that someone spends several years on what they disagree with. What is prioritized is whatever is “ours.” As an example, in 2011 we published and translated excerpts from the Azerbaijani satirical magazine Mollah Nasreddin, which I mentioned at the lecture. During the process there was a very delicate moment when we realized we were publishing rather harsh critique of Islam, in a satirical publication, during the scandal about the Danish cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad. We were afraid that by publishing at that time we could inadvertently add further fuel to the fires of Islamophobia.

We had to really consider whether it was worth going ahead with the project and what the repercussions could be. In fact, the original publishers of “Mollah Nasreddin” at the beginning of the 20th century were in some sense our opposite. Products of their time, they believed there is only one type of modernity: Western modernity and it needs to be imported to the Muslim world.

Can you tell us how your work is organized?

We work according to cycles of research and each cycle takes three to four years. These cycles never close entirely: we return to them, revise, add to them. Generally, the first two years are spent doing research or, let’s call it, a two-tiered research. We often begin with proper academic research. I work with a researcher who spends time at the library collecting material which she compiles and sends to us, which we then read. At this point the second part of research begins, the field work. We travel to the area or region relevant to the academic research to understand the lived component of the scholarly work. For example, when we did the Language Arts cycle we went to China’s Xinjiang region, where the Uighurs live, the only Turkic-speaking people to officially use the Arabic script. We explored how the language and writing of Uighurs intersected and interacted with Chinese state policy. In the early 1980s the Uyghur alphabet was changed yet again, from Latin to Arabic. There is an apocryphal theory that this happened because the People’s Republic of China foresaw the collapse of the USSR and understood that several new nations in Central Asia would exist for the first time as the result of that. China was afraid that if Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan gained independence, the Chinese Uighurs would also demand their independence. Finally, the most difficult stage in each cycle is how to translate this body of knowledge into art: whether sculptures, installations, objects, or lectures.

And you have a PDF version of each of your books available for free download on your site.

Yes, it’s a political decision. We work with different publishers and they are almost always against it. They plead with us "Please don’t put the free version on your site! Give us time to sell the book" and we simply answer: "Look, until we’re paid for our work for writing, designing, etc — we will decide how we make the book available …". We don’t make any money producing these books, have never received royalties for sales, why wouldn’t we give them away for free? A year after the publication of “Molla Nasreddin, ” it was selling for 600 or 1000 Euros online: this is very painful for us because books by nature should be affordable, especially vis-a-vis art.

You, I mean your collective, are a great example of a successful international community. Though, unfortunately, I can’t say that your case is a common story. Here, I would like to talk about the history of binaries: a person conditioned in the West looking to the East using schemes of Orientalism, and on the other hand a person of the East looking at the West through a system of stereotypes too. As the world is changing, information is now more easily available to everyone. Do we continue to live within these biases or is it no longer the case in your opinion?

Good question. Yes, I am afraid that we do still live in the midst of stereotypes, but as you yourself noticed in the last 5-10 years, some significant shifts of paradigms are taking place. But this requires a rethinking of our terminologis as well: left and right are increasingly inept to describe the scrambled political spectra. When we worked on the project “Made in Germany” we noticed a certain similarity between Russian and German orientalist studies. German Oriental studies were largely separated from politics and political decision-making, especially when compared to the French and English schools. The Germans studied ancient languages, for example Demotic, and tried to understand them through a theological context.

But, how, for example, did the policy of the Russian Empire and the USSR differ from other countries? This territory has both colonial and anti-colonial history. The Bolsheviks could not have been pure colonialists, this was contrary to their anti-imperialist ideology, but they still employed expansionist policies. England had to travel very far–say to India–to seize territory but Russia simply colonized their neighbors. The Turkic-speaking peoples, and peoples of the Caucasus region, they lived nearby. On the other hand, there is the history of Golden Horde and their colonial expansion as far as what is now broadly called Eastern Europe. Try to imagine India conquering of England in, say, the 14th century, and then 300 years later, they switch places and England colonized India. It deflates the so-called civilizing mission of the colonizer.

The oriental studies that interest us are ideas and people who used the teachings of the east to criticize their own system, without idealizing the East, or orientalizing it, as Edward Said eloquently argued. Speaking about the Muslim world, Vasily Bartold argued that in the 11-12 century, the peoples of Turkestan were more educated than the whole of the Christian world. How can we then consider them to be retrograde or depraved? In Islam there exists an idea of expatriation or self-exile. We must emigrate far, to another country, to another culture, language, in order to understand our own culture, our language, and this is very important. At present, the basic postulate of Western psychology is self-centered: to look inward, to go towards yourself, but this is complete nonsense! You can never understand yourself when you are next to yourself. Conversely, Eastern people could look more to the West, not to imitate or copy, but to understand themselves better. Unfortunately, today there is another danger and risk, an unexpected legacy of identity politics mixing with Said’s Orientalism and postcolonial studies: it is believed that a white person has no legitimacy studying Muslim culture, since they have no right to comment. And that kind of auto-centrism is very dangerous. So instead of a nuanced, critical field of studies, we have less and less work translating, distributing and expanding hitherto unknown thinkers, authors, texts, etc,

We seem to understand this, but when confronted with reality we yet again encounter boundaries. It seems that every kind of people diligently protect their personal space, or their statehood, fearing that it will be broken or taken away, fearing the expansion of other knowledge or language. Why does language play such an important role and why do language games become political games?

This is too big of a question, we would have to talk about it for several hours if not years. WIn our work we’re particularly focused on those things which are overlooked: namely, how alphabets accompany the empire. The Latin alphabet — Christianity, and then the secularism, the Cyrillic alphabet — Orthodox Christianity, then several centuries later communism, and the Arabic script — Islam. It’s like a vehicle. Why did we talk about letters yesterday? Nobody thinks about transcription, it is not considered something intellectual or as worthy as translation, which has university departments, esteemed scholars devoted to it. No one pays attention to the transcriptions.

And what is the problem here?

Signs are like advertising on the street, never simple or innocent.

Then let me repeat here a quote by Marshall McLuhan from yesterday’s lecture: “The Greek myth about the alphabet was that Cadmus, reputedly the king who introduced the phonetic letters into Greece, sowed the dragon’s teeth, and they sprang up as armed men. [. . .] Languages are filled with testimony to the grasping, devouring power and precision of teeth. That the power of letters as agents of aggressive order and precision should be expressed as extensions of the dragon’s teeth is natural and fitting. Teeth are emphatically visual in their lineal order. Letters are not only like teeth visually, but their power to put teeth into the business of empire building is manifest in our Western history.” In your project Friendship of Nations you work with the theme of the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran and the Solidarity movement in Poland 1989. On February 11 2019 it was 40 years since the end of the Islamic Revolution. Was revolution in Iran inevitable?

Perhaps it could have been avoided if the Americans had not interfered in Iran in 1953, when they organized the 1953 coup d’etat against Prime Minister Mossadegh and re-installed the Shah. The Iranian revolution was one of the most important events of the 20th century, as was the 1917 revolution. It was the first time someone had opposed American imperialism outside of Cold War proxies, that is without any help from Soviet Union, and was able to resist them. Since then, the United States has been obsessed with Iran.

So then how do you relate the revolution in Iran to the 1989 events in Poland?

1917 was the date that defined the 20th century, and the year 1989 of the Solidarity movement in Poland, was the end of what started in 1917. They are two book-ends. 1979 is the opening book-end of political Islam but we don’t have any idea when the closing book-end will be.

How important is it to look back in order to understand the present? The transcription of the past is also changing. The politics of memory and historical politics confirm this very well.

That’s exactly why it’s so important to acknowledge the unreliability of the past: how we feel about the past tells us a lot more about modern history than we think. To look into the future is pure speculation, and not of much interest to us. No one can tell me anything of real substance about the future. Not even Stephen Hawking had much to say about it. But with the past, I get to hear both your own or a collective opinion, because it has to do both with the personal and with a collective experience.