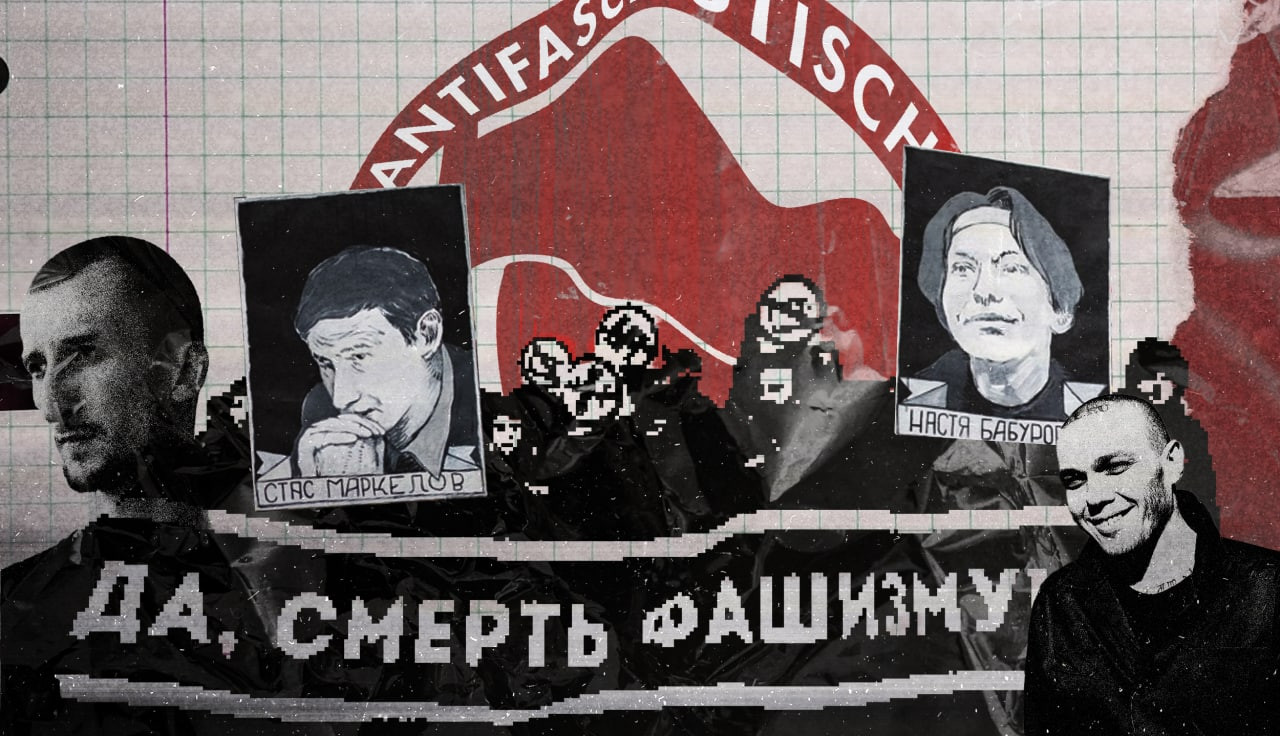

Being an Antifa: On Anti-Fascist Activism and Its Fate

Having unleashed a war on Ukraine under the pretext of “denazification,” the Russian state stakes its claim on yet another monopoly — this time, on anti-fascism. And yet a grassroots anti-authoritarian anti-fascist movement had existed all this while in the post-Soviet space. What was the movement like and what can today’s anti-war activists learn from it?

Below is a selection of contributions made by activists who took part in the anti-war conference CO/ACTION, which was held in Tbilisi in June 2022: on the Antifa movement, its fates and fortunes, and how to contend with the right-wing turn we face today.

Independent Researcher (preferred to remain anonymous)

With the onset of the war, dreams of the collapse of the Russian regime, long-cherished by politically active citizens, began to be shared by a growing number of people. Since February 24, I’ve been reading through quite a few social media posts in this vein. You can broadly group people’s prognoses for the future into two scenarios, one positive and one negative.

The negative scenario goes as follows: the current regime will endure, repressions will intensify, the gradual “fascization” of the country will continue, culminating in an open military dictatorship. The positive scenario proposes one or another collapse of the political system (be it as a result of a palace coup or mass protests), after which Russia will embark on a path of liberalization. I tend to share this positive outlook and think that we will see a radical transformation of the entire system of power. Yet I also think that a third scenario is plausible. Statistics can help to bring its contours into view.

Many would agree that, for all the costs and circumstances, Alexei Navalny is the most successful opposition politician in today’s Russia. Currently, his Telegram channel has over 270,000 subscribers and the total number of views for one of his posts is on average around 180,000. Those are pretty good numbers, especially if you take into account that Navalny is currently in prison and only posts rarely. Now, turning to the far-right — for example, to Igor Girkin (aka Strelkov), who, in his own words, “was the one who pulled the trigger of [the] war” in 2014. His Telegram channel has over 410,000 subscribers and an average post hits 349,000 views. So, his numbers are double those of Navalny’s.

The number of Strelkov’s subscribers has continued to grow since February. While supporting the war in principle, he, unlike other pro-war bloggers, has been very critical of the way it’s been conducted. Those who are interested in this kind of [militarist] critique typically either themselves come from the military or security forces, or are simply “fellow travelers.” We can even assume that these people have some access to weapons, as well as a certain experience of organized violence. The number of such people, evidently, is not insignificant in Russia.

In my view, too little attention is paid to right-wing activists, as compared with other opposition figures. It seems that people consider them to be part and parcel of the existing regime, its mere extension. I think this is a mistake. Yes, they do interact closely with the government but nonetheless, they have their own political agenda and goals. It’s enough to read through Strelkov’s programmatic article from this spring, “How We Should Set Up Ukraine,” in order to grasp how these people think — those we can designate the contemporary Russian right. Strelkov’s article is essentially a classically fascist pamphlet, based on the idea of society as an organic unity, whose body is threatened by nefarious elements that are alien to it — in this case, the liberal elites. He dubs their culture “bacterial” and among them, he pays particularly close attention to so-called “ethnic liberals” — well-known people of Jewish origin. The patriot’s task, in Strelkov’s view, is to cleanse the state body of these parasites, for which war provides the perfect opportunity. Victory in the war would enable not only the erasure of Ukraine from the face of the earth, the conversion of Ukrainians into Russians, but would also put an end to the disintegration of “Historical Russia.” Now let’s imagine a revolutionary scenario: suddenly, a government airplane crashes, or some other accident decapitates the power vertical. We see protests in the streets and tumult in the corridors of the state. Personally, I highly doubt that in this case, people like Strelkov would take the subsequent liberalization of the regime lightly. It’s much more likely that the far-right would take advantage of the situation and use its support base to seize power and impose its political program. This, in my opinion, would be our third scenario. To put it in other words, I think we need to take into account the probability not only of a liberal revolution but of a conservative one. In this regard, we need to work out possible counter-strategies in advance and form tactical alliances that would represent a counter-force. I think that in the face of a military junta, only a broad [anti-fascist] front would enable us to steer the situation in another direction.

Dmitry Okrest, journalist, editor of Being a Skinhead: The Life of Socrates, the Anti-Fascist

What in the experience of Russian anti-fascists could be useful for the contemporary anti-war movement? To answer this question, we should look at the history of anti-fascist activism. Alexey “Socrates” Sutuga, an anarchist and anti-fascist, died on September 1, 2020. He took part in ecological campaigns and street battles with the far-right. He was someone who, in the wake of the murders of several anti-fascists, began to guard punk concerts and anti-fascist rallies. He did two stints in prison on political grounds. He took odd jobs in construction, acted in a theater, and was working on a book [Prison Dialogues] about his prison experience. The book [Being a Skinhead: The Life of Socrates, the Anti-Fascist] that I later edited was an endeavor to keep his memory alive, relying on the testimonies of his comrades. It was equally an attempt to tell the story of the anti-fascist movement in Russia; to show what the “fat noughties” were really like.

The anti-fascism of the early 2000s united people from different subcultures (most often from the punk and hardcore scenes), political movements (above all, anarchists), and various ethnicities. After the revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine, the Russian authorities apparently made their wager on the far-right, seeing it as a potential weapon in their fight against the opposition. The end of the noughties was bloody: 15 anti-fascist activists were killed, there were pitched battles, and we saw the advent of the so-called “white car” — a moniker for the far-right’s practice of searching subway cars for “non-Russian” faces and beating them up. There were mine-strewn nightclubs and shootings from car windows. At the same time, many of the leaders of “football firms” were backed by officials and so managed to evade criminal sentences for their part in the violence. At first, anti-fascists simply protected each other; they later adopted a more proactive approach to self-defense. Everyone got into sports — it was a question of survival. The city parks were full of trainings in knife fighting and boxing.

Undoubtedly, the murders and repressions weakened the anti-fascist movement. Towards the end of the 2010s, anti-fascists began drifting towards media jobs and NGOs, IT and merch production, the vegan food and kraft beer industries. Former anti-fascist and anarchist activists began to have families and focus on their own affairs. Plus, they were faced with a choice: after the Khimki case, between subculture and activism; after Bolotnaya Square, between imprisonment and emigration; after Maidan, either staying above the fray or picking a side. Besides, there started to be fights among activists, ideological doublethink, skirmishes with random bystanders, internal squabbles and drug abuse. There was a belief that bygone feats would be enough to write all this off.

The old problems were still there and still relevant but the old solutions pointed to ever more danger. Today, many activists of that time are in exile, in prison or no longer alive. Some have grown up and simply withdrew [from the movement]. In the war between nazis and anti-fascists, nationalists and anarchists, it seems the state was the winner who took it all.

Moreover, the development of advanced surveillance systems and internet traffic analyses have rendered almost all anti-fascist resistance and its organization impossible. Nonetheless, in recent years you could spot the occasional headline about new cells of the national socialist underground, their attacks on LGBTQ+ and migrants and their fights with anti-fascists. That’s exactly why today I wanted to get back to this issue.

“Violence is an endless cesspit that traps everyone in its vortex” — as one of the book’s characters puts it. When I began talking with Sutuga’s comrades, it became clear how difficult it is for many people to remember that period. Some tried to repress their memories of detentions, fights and murdered friends — many refused to talk, even for the sake of this book. Yet, that very violence, at some point, saved those people. As veterans of the anti-fascist movement recall, violence is not something you should engage in and yet you have to be prepared for the possibility that all these stimulating discussions and debates will be followed by something else. Street politics will, one way or another, resume in Russia and we will need to be ready for it.

Vera, anti-fascist activist

I will share my perspective on the anti-fascist movement in Ukraine. Before finally moving to Kyiv in 2014, I used to travel there pretty often. There was a real sense of freedom in the air: you could talk freely, thrash out arguments, put forward your point of view. At the same time, there was always the threat from the far-right. Before Maidan, anti-fascist activists in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine held relatively common views about what to say and how to act. Various groups cooperated and co-organized their actions. For example, fans of Arsenal Kyiv undertook joint actions with Partizan Minsk fans, both clubs well-known for their anti-fascist stance.

The situation began to change with the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity, Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the formation of the ATO. The country was split into two camps: many anarchists joined the revolution, later signing up for volunteer battalions and fighting as part of the ATO forces; yet there were those who disagreed, calling the revolution “right-wing” and considering participation in ATO to be nothing other than cooperation with the state. During Maidan and the war in the east of the country, there was a ceasefire between anti-fascists and the far-right, though the right continued its sporadic attacks on those who held anarcho-communist views. In Russia, there was a small minority of anti-fascists who supported recognition of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) and the annexation of Crimea, and called all this “the people’s right to self-determination.”

I don’t think that what Ukrainian activists went through between early 2014 and February 2022 should be seen as a “right-wing turn.” Russia throughout this period was much more terrifying than the right-wing activists. Repressions in Crimea (among them, the anarchists Alexander Kolchenko and Evgeny Karakashev were targeted) offered stark proof that all civil and political rights had been eliminated on the peninsula. So in the fight for freedom against Russia’s dictatorship and terror in the occupied territories, anarchists’ goals coincided with those of the Ukrainian state and the nationalists. Today you can find libertarian activists in units of Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Forces. The LGBTQ+ community participated in the ATO and there was even a convoy of veterans as part of Pride in 2019.

There’s actually an interesting example of a “left-wing turn” by the erstwhile far-right. Avtonomniy Opir [Autonomous Resistance, or AO] is an organization established in 2009, formed by people who initially self-identified as fascists, national socialists and racists. In 2013, they adopted a national-anarchist agenda and began cooperating with other anarchists (becoming involved in campaigns to support political prisoners in Belarus and taking part in actions to free political prisoners, including Alexander Kolchenko and Oleg Sentsov). Feminists from AO were the first women to join in the armed defense of Ukraine. They took part in “Invisible Battalion,” a global advocacy project reporting on the challenges faced by women in the ATO. They also secured a statutory right to hold certain positions in the army and took part in combat operations, without being formally enlisted in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Bryan Gigantino, historian, writes for Jacobin and other journals

I’m from California but I’ve spent a lot of time in the post-Soviet space. To speak of the U.S., the anti-fascist movement there has a number of specific characteristics: it emerged not only as part of the ongoing struggle against capitalism but also in the context of the struggle against racism and in opposition to white nationalism. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the anti-fascist movement was aligned with the New Left, which was against structural fascism, racism and capitalism; against the oppression of the poor, African Americans, immigrants and the LGBTQ+ community — all at once. You could say that anti-fascism became a form of self-defense for discriminated communities: women, trans, queer people, immigrants, and so on. Within this movement, all these people — all of us — build solidarity with each other.

I was involved in the Antifa movement in Northern California in 2015-17, when the street presence of the alt-right and white supremacists, who murdered people in broad daylight, was growing ever stronger. At the time, American liberals said we should ignore the alt-right because any radical counter-action would only make things more difficult and erode public support for progressives. That’s why, at first, they refused to come out with us to protest against the fascists. Only when they grasped that the threat was real — when Heather Heyer was killed during the protest against the far-right rally in Charlottesville — did they finally take to the streets. Liberals, even here [in the U.S.], are not keen to associate with the left — nor are they ready to take action.

***

This text was first published in posle.media.