Rossen Djagalov. The Afro-Asian Writers Association and Its Literary Field

Rossen Djagalov is an Assistant Professor of Russian at New York University. We published a part of the second chapter of his book: “From Internationalism to Postcolonialism: Literature and Cinema Between the Second and the Third Worlds” as part of the publishing project «Tashkent-Tbilisi».

This part is about the history of Afro-Asian Writers Association, its literary field, crises it went through and the four major structures around which the Association constituted itself: international writers’ congresses, a permanent bureau, a multilingual literary magazine, and an international literary prize.

The Afro-Asian Writers Association as a Field

The Afro-Asian Writers’ movement founded in Tashkent (the Afro-Asian Writers Association would be formally inaugurated at the Second Congress in Cairo in February 1962) was thus part of a larger ecology of competing internationalisms in which the literatures of these continents were becoming integrated. But what was that Association itself? Shridharani’s article points to the two very different perspectives from which it could be studied. On the one hand, it functioned as a site of South-South solidarities, of forging unpredictable but fruitful connections among writers and readers otherwise separated by geography, language, and national culture. Any examination of the literary texts published in the Association magazine, Lotus, or of the writers’ accounts of meeting at the Association’s congresses lends itself to frameworks such as imagined community or transnational public sphere. On the other hand, the Association, like previous Soviet-affiliated literary formations, could be viewed as a Cold War front structure meant to give Soviet cultural bureaucracies a measure of influence over Afro-Asian letters. Indeed, should a researcher limit her study of the Afro-Asian Writers Association to the transcripts of the Soviet Preparatory Committee or the Association’s official resolutions, she would only confirm her suspicion of the Association as a propaganda vehicle for Soviet, Chinese, Egyptian, and even Indian foreign policy.

Referenced earlier, Bourdieu’s notion of a field productively synthesizes these two divergent perspectives and avoids their attendant normativities [1]. Like any field, Afro-Asian literature operated as an arena of struggle for authority by its most powerful member-states (the USSR, China until the mid-1960s, Egypt until 1978, India). However, its existence cannot be reduced to the quest for domination. To exist as a field in the first place, it had to achieve a degree of internal cohesion and boundedness with respect to the outside. The outside, in this case, was Western literature, which dominated the bookshelves of African and Asian bookstores and libraries. The diverse agents of the Afro-Asian literary field — writers, cultural bureaucrats, publishers, critics, and readers — intuitively shared with contemporary dependency theorists such as Samir Amin, Raul Prebisch, and Walter Rodney an understanding of how they could escape their peripheral position within world literature: by delinking from the larger (literary) world-system, which kept them in a subordinate position; by developing their (literary) resources through interconnections; and by setting the terms of their own presence on the world (literary) stage. The Afro-Asian Writers Association represented just such an attempt to gain some autonomy from Paris and London and their interpretative authority.

For these reasons, what distinguishes the Afro-Asian Writers Association from previous Soviet-affiliated writers’ associations is its geographical boundedness. The internationalism of those formations such as MORP, the Writers for the Defence of Culture, or the Intellectuals for the Defence of Peace was, technically at least, a worldwide internationalism. By contrast, Afro-Asia was explicitly inscribed into the title of this writers’ formation. The inclusion of the Soviet Union — a state straddling Europe and Asia, but with a mostly white population and an uncomfortable imperial history — posed particular challenges: while most of the Soviet writers who participated in the Association came from Central Asia, two of the chief Soviet representatives at the Association — Anatoly Sofronov and Aleksei Chugunov — were decidedly European.

Occasionally, the question of including Latin America would be raised at some of the meetings of the Association [2]. That never happened, most likely because of Latin America’s combination of right-wing pro-American governments and radical (but not Moscow-oriented communist) writers, which was deemed potentially too disruptive for the fragile equilibrium that held the Association together. As a result, the enormously popular Latin American boom remained decoupled from the Afro-Asian Writers movement. The Soviet participation opened the door to other delegates from Eastern Europe — as observers, to be sure — further stretching the definition of the Afro-Asian writer [3]. At the same time, because of the Israeli occupation of Palestine, the Egyptian delegation made sure that Israel would never be invited. Similarly, at the insistence of the Chinese writers, their Taiwanese colleagues could not qualify for Afro-Asian status. As long as China remained part of the movement, the latter never received an invitation to any of the Congresses. In the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s, the China Writers’ Association, one of the founding and most authoritative participants, boycotted the Afro-Asian Writers movement (or more precisely, as we shall see, founded its own, parallel one), creating a major white spot on its bicontinental map.

That the Association was organized in a national framework and many countries’ delegates acted as state representatives tied its fortunes to the vicissitudes of interstate relations. Every international political conflict was reflected in the works of the Afro-Asian Writers Association and its definition of Afro-Asian literature. Even the Soviet side, notorious for making its own local agenda part of the general discussion, would often complain about local squabbles, such as the Arab writers’ conflict with their Egyptian counterparts in the aftermath of the Camp David Accords, which threatened to derail any other agenda [4]. Indeed, a significant portion of every political statement at the conference addressed the struggles of the Palestinian people. Reflecting the political make-up of the Association’s organizing committees, a lengthy list of concrete political causes defines the Afro-Asian writer in most of its declarations such as the following one from 1976:

"We, the writers of Africa and Asia… represent 23 Afro-Asian countries, 10 East European countries [italics are mine — RLD] and cultural, regional and international organization…

We now witness in Asia the prominent historical victory of the peoples of Indo-China over the aggression of American imperialism…

We, the writers of Asia and Africa, greet our militant brethren in the People’s Republic of Angola, under the leadership of our great poet, President Neto, and his comrades in the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola…

We, the Afro-Asian writers, declare our unreserved support for the movement of the valiant Palestinian Resistance…

We, the writers of Asia and Africa, join our voice to the voice of the whole civilized world, which has condemned Zionism as a racist theory and movement.

We, the Afro-Asian Writers, hail the prominent role played by socialist countries, foremost among which is the Soviet Union, in consolidating the national liberation movement in Africa and Asia. We affirm the necessity of strengthening the strategic alliances between socialist forces, world national liberation forces as well as democratic forces in the capitalist world with a view to reshaping the face of the world for liberation, independence, democracy, and social progress. [5]"

Thus defined, via concrete geopolitical struggles, the Afro-Asian literary field became a function of the Third-Worldist political project and largely reflected the latter’s fortunes. Moreover, while the above quotation does not reproduce the 1976 Declaration in its entirety, there is no particular item from that lengthy list that references any particular aesthetic the Association championed. A broadly defined realism, nevertheless, remained the most likely candidate for the Association’s common aesthetic horizon, as Soviet delegates would occasionally assert [6].

At its purest, the Soviet effort to gain political influence among foreign writers comes out in the transcripts of the Foreign Section of the Soviet Writers Union and the Soviet Committee for Solidarity with Africa and Asia. With the Afro-Asian Writers Association, the Soviet side, in particular, lacked the kind of unquestionable authority — moral and organizational — it had enjoyed over previous associations, especially the World Peace Council. At a time when the self-confidence of the writers of these two continents as a new and emerging formation ran so high, the Soviet side took care not to appear as if it were co- opting the Association. Indeed, throughout the existence of the Association, Soviet representatives faced complex and constant choices whether to co-opt or confront, to humbly swallow speeches against white domination or challenge them. As a successor of an empire and as a mostly white society, the Soviet side continually needed to justify its place at the table.

The writers from the other three founding member-states, China, Egypt, and to a lesser extent, India, also acted as extensions of their national diplomacies. As a result, every political tension or crisis in Third Word geopolitics was replicated in the history of the Association. Heterogeneous though they were in their views, Indian writers for the most part observed the Indian Congress Party’s reserved stance in geopolitical matters, thus at various congresses proving the greatest obstacle to the efforts of the Soviet, Chinese, and Egyptian delegations to politicize the Association’s initiatives and vision of literature.

A much more severe, in fact, near-fatal crisis, in the life of the Association was caused by the Sino-Soviet split of 1960, which initially blocked its activity and eventually resulted in two competing organizations — a pro-Chinese Afro-Asian Writers Bureau and a pro-Soviet Afro-Asian Writers Association. Beyond fiery denunciatory speeches and conspiratorial committee meetings, the struggle between them took multiple forms such as the Chinese writers furtively waiting in the corridors of the 1967 Beirut Afro-Asian Writers Congress, handing out their anti-Soviet leaflets and inviting a bemused Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o for a conversation [7].

The Egyptian centrality to the Association, at least in the decade-long period when Cairo hosted both the Permanent Bureau and Lotus’s editorial offices, occasionally aggravated Soviet cultural bureaucrats. Expressing a common sentiment, the Chukchi writer and member of the Preparatory Committee for 1973 Alma-Ata Congress Yuri Rytkheu stated: “Lotus is situated outside of our influence — this is perfectly clear. Maybe we should pose the question of the physical presence of one of our representatives [in the Cairo editorial offices] so that we could steer it our way.” The Moscow-Cairo axis continued to be central to the Association’s work until the late 1970s, when Egypt’s President Sadat, who succeeded General Nasser in 1970, practically switched his country’s allegiance from the USSR to its Cold War adversary and made peace with Israel, angering most Arab intellectuals and writers [8]. If the Association managed to recover from its major crisis (the Sino-Soviet split), Egypt’s withdrawal plunged it into a state of permanent instability.

And while Arab writers (especially those united around the cause of Palestinian liberation) remained central to the Association even after the Camp David Accords, sub- Saharan Africa’s role grew increasingly prominent, as reflected by the election of its new general secretary, the South African writer Alex La Guma, and, in 1979, the setting of its Sixth Congress in Luanda, the capital of the newly liberated Angola. The president of that country, the Lotus-prize recipient Agostinho Neto, played the role of the Congress’s symbolic host. The Soviet Preparatory Committee’s discussion of La Guma’s choice on the eve of that Congress speaks volumes about the Soviet organizers’ patronizing perspective on the Association:

[Sofronov:] "I remember La Guma. I had to meet him on quite a few occasions. He gets carried away sometimes and says that he hates it when other people dictate to him what to do

… But La Guma is our kid [nashe ditia]. We proposed him at the Alma-Ata Conference against al-Sibai’s and Mukherjee’s wishes. Mukherjee [the other candidate for the position] — is a wild man while he [La Guma] grew up in the communist underground, 11 years in prison and house arrest, and so on. And by the way, he is a good writer. That’s nice [9]".

Secondarily, the by-the-way quality with which Sofronov brings up La Guma’s literary talent is revealing of the role aesthetics played in the eyes of the Soviet organizers. The language of control and “usefulness,” combined with some apprehension of La Guma’s independence emerges in E.A. Kryvitsky’s response to Sofronov:

“We knew that La Guma would be no sugar. We were not confused in this respect. But at the same time we knew that there are particular ways of approaching him, which would make him very useful for us. This is obvious. Considering his weaknesses, let us use his strongest side. [10]”

Whatever measure of influence Soviet cultural bureaucracies sought and obtained in supporting the work of the Association, it certainly did not translate into literary practice. The mechanisms of control they had over Soviet writers — censorship, membership into the Writers Union, with all its available carrots and sticks — were poorly applicable abroad. Even such African and Asian graduates of Moscow’s Gorky Literary Institute (the leading creative writing program in the USSR) as Maithripala Sirisena (future president of Sri Lanka), the above-mentioned Atukwei (John) Okai, and scores of Arab writers could hardly be thought of as orthodox socialist realists and conduits of Soviet influence abroad. By contrast, attraction from afar — the circulation of Russian or Soviet literary texts and their novel interpretations — among Afro-Asian audiences proved much more influential, and not in a way the Soviet state could have controlled. [11]

The Structures of the Afro-Asian Literary Field

Arguably, the main form that Soviet influence took was not in the struggles over geopolitical orientation but in the structures of the Afro-Asian literary field, which derived from earlier iterations of Soviet literary internationalism, such as the International Union of Revolutionary Writers (MORP) of the early 1930s, the Popular-Front-era Association of Writers for the Defence of Culture, and the early Cold War World Peace Council. The following section will identify and reconstruct the lineage of the four major structures around which the Afro-Asian Writers Association constituted itself: international writers’ congresses, a permanent bureau, a multilingual literary magazine, and an international literary prize.

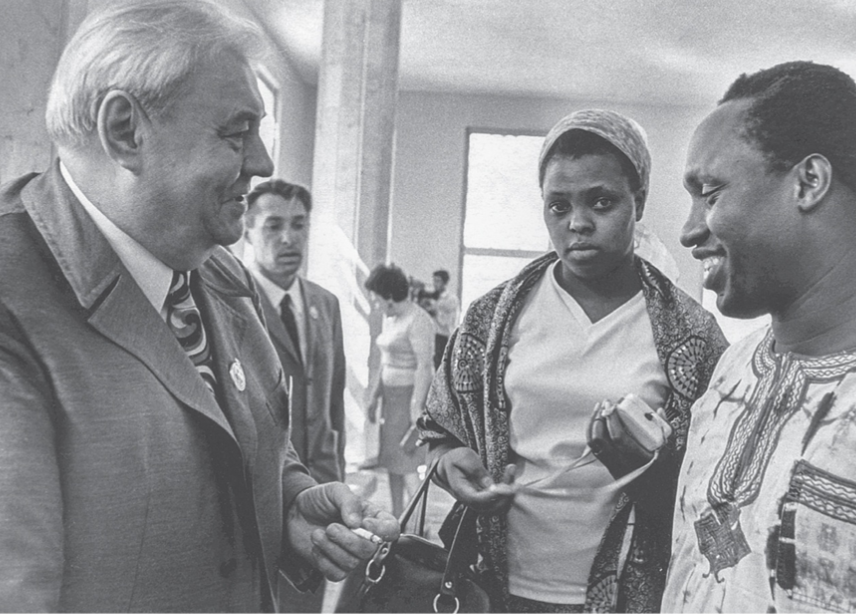

The most visible of these were the Afro-Asian Writers congresses at which writers from the two continents would descend upon a city for a week, providing what we would nowadays call a media event as well as an opportunity for them to announce themselves as a movement and determine its direction. In practice, congresses would be divided into official proceedings, a cultural program organized by the hosts in the city and beyond, and a less structured time for informal get-togethers with other writers or sightseeing, which of course could always be expanded at the expense of the official proceedings. The official proceedings were usually the least memorable part, but sometimes they would feature heated debates such as those that occurred during the Second Congress, held in Cairo, when the Sino-Soviet rivalry was played out in the open. As a whole, the congresses gave visibility to what were largely two imagined communities of Afro-Asian writers, on the one hand, and their readerships, on the other. Indeed, the local organizers of those congresses emphasized their guests’ relations with reading publics from their country by facilitating formal and informal meetings between the two and showcasing local translations of the visitors’ works. Illustrating the writers’ commitment to progressive causes, at the end of each Congress, resolutions were passed on political issues such as ongoing independence struggles, military invasions, and disarmament.

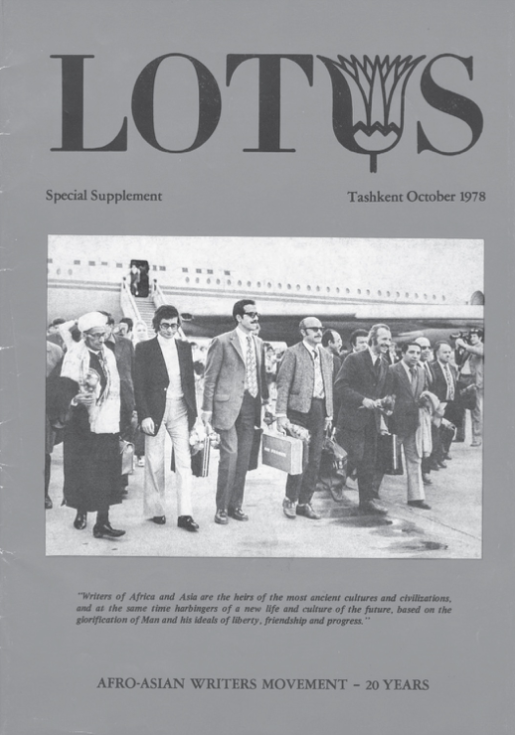

Not unlike the gatherings of previous, Soviet-affiliated international writers’ formations — MORP’s Moscow (1927) and Kharkov (1930) conferences, the Association of Writers for the Defence of Culture Paris (1935) and Valencia-Madrid-Barcelona-Paris (1937) congresses, and the World Peace Council’s Wroclaw (1947), Paris/Prague (1949), Sheffield/Warsaw (1950) assemblies — writers’ congresses would be the main feature of the Afro-Asian Writers Association. Starting with the 1958 Tashkent Congress, Afro-Asian writers would similarly come together at seven other congresses: held in Cairo (1962), Beirut (1967), Delhi (1970), Alma-Ata (1973), Luanda (1979), again in Tashkent (1983), and finally in Tunis (1988). In between the larger congresses, the Association would hold regular meetings of the Lotus editorial board, and conferences, such as a poet’s gathering in September 1973 in Yerevan, a young writers’ meeting in Tashkent in the fall of 1976, and smaller anniversary conferences, also in Tashkent, held in 1968 and 1978.

The Soviet organizers published (in Russian) the transcripts of the first five congresses. It is difficult to evaluate the overall significance of the official proceedings, between the excerpting of the speeches, which smoothed conflicts or rough edges, and the nature of such formal events. For many participants, as Shridharani’s coverage of the Tashkent Congress makes abundantly clear, it was not the formal resolutions passed by the congress or the individual speeches that left the most powerful impressions but rather the encounters and conversations outside of the conference hall, with locals or fellow visiting writers, some of which, as Shridharani’s, were recorded in articles or other autobiographical writing [12]. Each of these tells us as much about its author’s perspective as it does about the congress. Nevertheless, many of the motifs of Shridharani’s article recur twenty years later, in the travel notes of the radical feminist Afro-American poet Audre Lorde, an invited American observer to the 1976 Young Writers Conference in Tashkent [13]. A not unsympathetic commentator, she is less taken by Soviet modernity (unlike the other delegates, she is, after all, visiting from New York) but does admire the bread, the free healthcare, and education, which the Soviet state — unlike the United States — guaranteed for its citizens. Reading her notes, one can sense the difference between her more distanced interactions with Russians in Moscow, where she visited the Soviet Writers Union, which had formally invited her, and the warmth and engagement she feels for the people of Uzbekistan:

"As we descended the plane in Tashkent, it was deliciously hot and smelled like Accra, Ghana… I felt genuinely welcomed… I had the distinct feeling here, that for the first time in Russia, I was meeting warm-blooded people; in the sense of contact unavoided, desires and emotions possible, the sense that there was something hauntingly, personally familiar — not in the way the town looks because it looked like nothing I’d ever seen before, night and the minarets — but the tempo of life felt quicker than Moscow; and in place of Moscow’s determined pleasantness, the people displayed a kind of warmth that was very engaging. They are an Asian people in Tashkent. Uzbeki…

If Moscow is New York, Tashkent is Accra. It is African in so many ways — the stalls, the mix of the old and the new, the corrugated tin roofs on top of adobe houses. The corn smell in the plaza, although plazas were more modern than in West Africa…

And it’s not that there are no individuals who are nationalists or racists, but that the taking of a state position against nationalism, against racism is what makes possible for a society like this to function. I remember the Moslem woman who came up to me in the market place, asking Fikre [a Patrice Lumumba University student from Ethiopia accompanying Lorde — RLD] if I had a boy also. She said that she had never seen a Black woman before, that she had seen black men, but she had never seen a Black woman, and that she so much liked the way I looked that she wanted to bring her little boy and find out if I had a little boy, too. Then we blessed each other and spoke good words and then she passed on. [13] "

The actual Afro-Asian conference takes much less space in Lorde’s travel notes. She is disappointed to find “only four sisters in this whole conference,” unclear about her “observer” status as an African-American, and unhappy about the absence of a meeting for oppressed peoples of Black America given the abundance of “meeting[s] of solidarity for the oppressed people of Somewhere.” [14] The strict geographical demarcations of Afro-Asian solidarity left little space for her.

In between congresses — periods that could last a long time because of the Afro-Asian Writers Association’s multiple crises and the inertia of its last decade — day-to-day decisions about the Association’s running were made by a headquarters, an international bureau not unlike those previously coordinating the national sections of MORP and the Association of Writers for the Defence of Culture. Initially located in Colombo, Sri Lanka, as a neutral location equidistant between the great powers of the Association, it was presided over by the chairman of the Sri Lankan Union of Writers, Ratne D. Senanayake. The latter’s decision to side with China during the Sino-Soviet split caused the first and nearly fatal crisis in the life of the Association [15]. That period of internal strife was reflected in the five-year gap between the 1962 Cairo and the 1967 Beirut Congresses during which much of the Association’s activity was paralyzed. As the Bureau was the main decision-making organ of the Association between congresses and those were not taking place, the Soviet side even contemplated abandoning the Afro-Asian format and devoting their energies to a new, African Writers Association, which would be free of Chinese influence [16]. Eventually, the Soviet and the Egyptian sides organized an emergency meeting in 1965 at which it was decided to move the Permanent Bureau to Cairo and replace Senanayake with the Egyptian novelist Yusuf al-Sibai (1917–1978), the general secretary of the Afro-Asian Solidarity Organization [17].

In the face of this decision, the Colombo-based Afro-Asian Writers Bureau did not back down and fold but continued to function as the focal point of Maoist literary internationalism, publishing a number of volumes of Afro-Asian poetry, model Peking operas, Maoist propaganda, and even a short-lived and nearly unfindable English-language literary journal, The Call. This effort to compete internationally with the pro-Soviet Association came to an end with the purges of the Cultural Revolution and the general solipsism into which the Chinese cultural policy of the late 1960s collapsed. While, as Duncan Yoon has shown, literary Maoism may have commanded the sympathies of individual Afro-Asian writers, it was a brief phenomenon and hardly a match for the cultural capital and material investments of the Soviet-Egyptian-Indian literary alliance [18].

The decade during which Cairo hosted the Permanent Bureau of Afro-Asian Writers was a period of stability and growth. It ended abruptly in 1978 with the Camp David Accords, and al-Sibai’s assassination earlier that year by Palestinian militants upset with his personal support for the peace treaty with Israel. This dual loss — both of a founding member-state of the Association (Egypt) and of somebody who had been by all accounts a capable, committed, and well-connected organizer (al-Sibai) — initiated a period of uncertainty and homelessness, which was never fully resolved until the very end of the Association ca. 1991 [19]. In this last decade or so, the Bureau’s fortunes became intimately tied with those of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), which first hosted it in Beirut until 1982, when the start of the Lebanese Civil War and Israeli bombing drove the PLO out of town, and then in Tunis. At the same time, al-Sibai’s successor as the Association’s general secretary for most of this period, the South African writer Alex La Guma (1925–1985), lived in Cuba, as a representative of the African National Congress, and could not follow the day-to-day running of the Permanent Bureau.

The Bureau (at least during its Cairo phase) hosted the Association’s literary quarterly, Lotus (1967–91), which offered the most tangible proof of the existence of an Afro-Asian literary field [20]. While the idea of a journal was broached as early as the 1958 Tashkent Congress, a detailed plan for a magazine with a circulation of about 5,000 copies and length of about 150 pages (Lotus’s eventual parameters) had to wait until 1963, when Faiz Ahmad Faiz submitted his proposal to the Soviet Writers Union [21]. It was based on multiple conversations with writers, editors, and politicians in Beirut, Cairo, Paris, and Geneva, and was made weightier by Faiz’s recent receipt of a Lenin Peace Prize. In a lengthy preamble, he explains the need to counter several already existing hostile publications: on the one hand, the jewel in the crown of the CIA-sponsored Congress for Cultural Freedom, the Anglo-American Encounter, which, over the course of the 1960s, under the editorship of Stephen Spender and Melvin Lasky, had increasingly turned its sights to (formerly) colonial literatures, and its allied publications in Asia; on the other, against two English-language Maoist magazines, the Hong-Kong-based Eastern Horizons and the Geneva-based Revolutions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America [22]. As the ideal location for such a magazine, Faiz proposes Beirut: in his view, the city combines an excellent geographical location with an abundance of local writers and politicians supporting the cause, good publishing and distribution facilities, and a relative paucity of censorship restrictions, which he feared might cripple the magazine if it were to be founded in Cairo [23]. Faiz’s initial project was not realized untill 1967 when Afro-Asian Writings began publishing prose and poetry, literary criticism, and book reviews by writers from all over the two continents. (At Mulk Raj Anand’s instigation, the international editorial board decided to change the title to Lotus during a 1969 meeting in Moscow.) [24]

Faiz, however, had proposed an English-language magazine explicitly modelled after Encounter. Just like Encounter, he insisted, it should be prepared to publish major writers without “clear political views” and even material hostile to its agenda (as long as it is effectively countered). [25] His efforts to broaden the ideological parameters of the magazine ran against the model Soviet cultural bureaucracies had in mind: International Literature, the Moscow-based literary organ of the worldwide Popular Front. Indeed, as Faiz would discover later, during his five years at the helm of Lotus, it resembled International Literature in it unswerving loyalty to its hosts and sponsors — the USSR, Egypt, the PLO [26]. Another — more striking — commonality of the two magazines was that they simultaneously published issues in several languages: French, English, and Arabic in the case of Lotus; Russian, German, French, English, and, occasionally, Spanish and Chinese, in the case of International Literature [26]. Through translation, they sought to overcome the national and regional boundaries dividing their intended readership and to forge a truly international reading public, spanning Africa and Asia.

With only 5,000 of each issue printed in each language, Lotus could hardly reach numerically significant readerships in Africa or Asia, but a consistent effort was made to send it to libraries and writers’ organizations in the two continents and beyond. For its distribution, it relied on its own transnational networks as well as on foreign publishing companies such as the French Maspero or the British London Publishers [27]. Practically, every aspect of the journal was international: not only the contributors and the readers but also its peripatetic editorial offices (Cairo, and after the Egyptian “defection,” Beirut, and Tunis) and the location of its printing press (Egypt, for the Arab version; East Berlin for the English and French ones). The international editorial committee was spread among Algeria (Malek Haddad), Angola (Fernando da Costa Andrade), Iraq (Fouad al-Takerly), Japan (Hiroshi Noma), Lebanon (Michel Soleiman), Mongolia (Sonomyn Udval), the USSR (Anatoly Sofronov), India (Mulk Raj Anand), Pakistan (Faiz Ahmad Faiz) and Senegal (Doudou Gueye). After al-Sibai’s assassination, Lotus’s helm passed on to Faiz, who edited it out of Beirut until 1982. In the last and probably least documented part of its history, when publication and distribution grew increasingly irregular, Lotus was first briefly run by Faiz’s deputy, the Palestinian poet Muin Bseiso, and later, after his death, by the PLO’s chief press officer, Ziad Abdel Fattah.

Lotus’s pages also reflected this imperative to cover as many national literatures in as many different genres as possible. The limited number of pages available meant that, unlike International Literature, it could not easily lend them to novels, so the main genres represented were short stories and selections of poetry. The magazine did not limit itself to literature but included neighbouring arts as well. In addition to the occasional play or folklore, most issues included several pages of images, whether of paintings or art objects, accompanied by a detailed explanation. The articles in the Studies section, prepared especially for the magazine, exhibited a certain regional or (bi)continental focus: “The Role of Translation for Rapprochement between the Afro-Asian Peoples,” “The Popular Hero in the Arabic Play,” “Where does African Literature go from here?” Occasionally a single author or national literature would be showcased, for example, “Ghalib and Progressive Urdu Literature.”[28] Rounding out each issue were book reviews as well as a chronicle of current events of Afro-Asian literature. Such chronicles helped foster a sense of simultaneity and coherence of the whole among the bicontinental readers. Not unlike Benedict Anderson’s newspaper, which helped its readers imagine the nation by placing next to each other articles on a natural disaster in province X and on a major cultural event in the capital, such chronicles or book reviews constructed the category of an Afro-Asian literature by placing its geographically dispersed manifestations alongside each other [29].

The fourth and last structure through which the Afro-Asian Writers Association sought to consolidate Afro-Asian literature as a coherent field was the Lotus Prize. Awarded between 1969 to 1988 to leading Afro-Asian writers, it was modelled after the World Peace Council’s Stalin Peace Prize given to writers, artists, and scientists who had contributed to the cause of world peace. The World Peace Council established its award at the hottest moment of the Cold War, as a more political and less Western alternative to the Nobel Prizes for Literature and Peace. By the same token, the Lotus Prize acquired the reputation of an Afro-Asian Nobel for literature, at a time when very few African and Asian writers were awarded an actual Nobel. In the process, it contributed to the production of an Afro-Asian literary canon. The success of this prize is reflected in the continued fame of its recipients: the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish and the South African prose writer Alex La Guma (the 1969 awards); the Angolan poet-president Agostinho Neto (1970) and the Senegalese novelist Sembène Ousmane; the Algerian Kateb Yasin and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (both in 1972); Chinua Achebe and Faiz Ahmad Faiz (the 1975 awards) are still among the best-known Afro-Asian writers. Some of them, like Mahmoud Darwish and Alex La Guma, received the award well before they reached the peak of their fame in the West [30] There is no uniform aesthetic unifying the diverse writing of its recipients: the modernism of the older Egyptian novelist Taha Hussein, the militant anti- colonial verse of the Mozambican militant poet-independence-fighter Marcelino dos Santos, Aziz Nesin’s biting satire of Turkish state and society, and Chinghiz Aitmatov’s unique synthesis of socialist and magical realism.

Judging by the transcript of the discussion of the first batch of Lotus awards, its principles were not particularly well-codified, giving the prize committee a good deal of flexibility [31]. The award could be given not only for individual work but also for overall contributions to the Afro-Asian Writers Association; it would be desirable if at least one award (out of the six awarded for 1969–70) would go to a writer from a country fighting for independence. Palestinian literature was the major beneficiary of this last principle: in the first ten years of the award’s existence, Palestinian writers won five Lotuses, making them the absolute leader in this regard. (By the time the last Lotus was given in 1988, Soviet prize-winners had overtaken them.) By the same token, as literatures fighting a foreign occupation, Vietnam and Lusophone Africa (Angola and Mozambique) were given four prizes each, making them a joint third. The Lotus Prize was only one of the ways through which the Association facilitated the Palestinian and other anti-colonial struggles for international cultural recognition. Otherwise, the Lotus Prize committees sought the widest geographical representation of its awards. The non-inclusion of a francophone African writer among the first six recipients became the main source of contention during the inaugural meeting of the Lotus Prize Committee in 1970, when the Senegalese representative Doudou Gueye asked that his protest be officially registered in the proceedings [32].

While geography seems to have been a major consideration in selecting Lotus Prize winners, gender balance does not seem to have been a factor. In fact, of the fifty-nine awards that were given, only two went to women: the Uzbek poet Zul’fia and the Mongolian prose writer Sonomyn Udval. This poor representation of women was hardly limited to Lotus Prizes but extended to all other aspects of the Afro-Asian Writers Association: the awards were made by the nearly all-male Lotus editorial board, which in turn published mostly male writers.

Gradually, the award experienced a Brezhnevization of sorts. In a discussion of its workings in the Soviet Writers Union following the Association’s last conference in Tunis (December 1988), one perestroika-minded Writers Union official, Yevgeny Sidorov, revealed what the main criterion for the Lotus awards over the previous decade had become: if you were a literary official heading your national section of the Afro-Asian Writers Association, sooner or later you would receive your Lotus [33].

The congresses, the permanent bureau, the literary quarterly, and the Lotus Prize were only the most visible structures of the Afro-Asian Writers Association. Underneath them lay a whole network of nation-based committees, publishing houses, magazines, and translators located within different African and Asian countries, who were performing the much less visible work of bringing foreign literature produced within the two continents to their national readerships. Lydia Liu has called this engagement the Great Translation Movement [34].