Encapsulating internal agony: Trauma in modern experimental horror movies

Thinking about history and epistemology, art mediums convey properties of current context, obviously, beginning with ancient theater, medieval iconography, and ultimately, with the development of visual arts and their transformation beyond the boundaries of painting and graphics, it continues in cinema and photography. So, what can be said about art tendencies right now, since the state of the world is confused even when it comes to terminology amongst big researchers [1]? Nevertheless, postmodernism, as being a major dominium of the unconscious collective personality for a long time, creates a (historical) materialistic link with global trends that encompass all aspects of life and which exist at a primordial level and is instilled in a person from birth a priori.

Terry Eagleton, in "Illusions of Postmodernism," sets the parameters of internality and externality as total deconstruction of meaning and the post-structuralist ideology of destruction [2]. From this, constant negation emerges — the denial of lived experience, reducing it to irony. However, recently, new works of art and mass entertainment have shifted in the opposite direction — replacing postmodern irony with the deconstruction of the meaning of deconstruction itself. In other words, in the realm of art, there is a revival of an attempt to find meaning, but in a new, altered form of collective consciousness that has experienced the twentieth century, an analog of which had not occurred in history before.

When it comes to the horror genre in the classical sense, the audience is familiar with different subgenres — slashers, gore, monster movies, psychological thrillers. However, in recent years, the experimental side of the genre has acquired new properties, which would be addressed as a "trauma-exploring subgenre" that actively develops and is passed from film to film. This phenomenon does not have a clear definition; it is more of an affective state in which this cinema is created and perceived: through the prism of the analysis of trauma.

It is important to determine how "horror movies exploring trauma," which form a separate trend within experimental films, are classified. Firstly, they are distinguished by a particular narrative structure — usually presented in a fragmented manner, often with an open ending (below, it will be explained why this subgenre more frequently employs open endings compared to other subgenres in horror films, including contemporary ones). The goal of experimental trauma horror movies, in one way or another, is to open up a dialogue with the viewer by projecting the characteristics of the main characters onto them. Unlike classical and mainstream horror films, this subgenre does not seek to "distance" the viewer to a safe distance by employing established horror archetypes (for example, "the last girl" in slashers), creating "faceless" protagonists, and highly atypical circumstances. On the contrary, trauma exploring horrors strive to bring the viewer closer to the narrative, literally "incorporating" their identity into the framework of the plot: "this could have happened to me." Therefore, it is not enough to solely focus on the narrative elements of such experimental horror films and analyze the plot, but rather examine the phenomenon of new tendencies within experimental cinema as a whole — why did such movies emerge? Why are there so many? What are the main motives, leitmotifs and traditions that are starting to emerge and gain a foothold in this young subgenre?

Kabalek, Elm and Kohne write about the phenomenon of trauma in contemporary sociology as follows: "Thus, history is reformulated as traumatic non-representability — in other words, postmodern historiography is replaced by traumatology. [3]" Here we return to the phenomenon of complete postmodern reconstruction. In horror films that explore the theme of trauma and the experience of affect, historiography is sublimated into a clinical context. Classic (and simply following traditions) horror films frighten with veiled allusions in the imagery of monsters, maniacs, serial killers, and "perverted creatures" in any form they may take — thus, these films exist due to a) consumerist tendencies set by society at the time: serial killers become interesting characters in the horror films of the 60s-70s because of the emergence of "great" serial killers who entered history, and b) initially unreadable criticism of social phenomena — as seen in the films "The Fly" or "The Thing." Talking about viewers’ interest in particular themes, it is also crucial to mention popular economy as one of the factors by which different subgenres and approaches within them started being enshrined in the tradition: “if people want to see something particular, they will, thus we shall create more and more.” At the same time, the viewer feels a distance from what is happening on the screen — these monstrous creations, in whatever forms they may be presented, still remain something unattainable and incomprehensible.

Trauma itself is an unattainable, irrational property: Jeffrey Alexander, referenced by Julia Koch and Michael Elm in the book "Violence Void Visualization," writes in "Trauma in a Social Theory" about the clinical-sociological phenomenon of trauma as a change in consciousness, not related to the event itself, but to a radical upheaval (collective or individual) that initiates the process of representation through the imaginary. “Imagination is intrinsic to the very process of representation. It seizes upon an inchoate experience from life, and forms it, through association, condensation, and aesthetic creation, into some specific shape.”; “The psychoanalytic version of lay trauma theory goes beyond the Enlightenment one: “Trauma is not locatable in the simple violent or original event in an individual’s past, but rather in the way it’s very unassimilated nature — the way it was precisely not known in the first instance. [4]”

Horror movies that depict and explore trauma go beyond just collective guilt or the analysis of historical events, as conventional horror movies do. They transcend the collective and narrow down to the individual, yet still remain collective in nature. "(…) The collective trauma works its way slowly and even insidiously into the awareness of those who suffer from it, so it does not have the quality of suddenness normally associated with "trauma." But it is a form of shock all the same, a gradual realization that the community no longer exists as an effective source of support (…). [5]" In order to explain the thesis of the transition from collective trauma to individual and then back to collective, it is desirable to consider several experimental films made in recent years and only then elaborate.

Subgenre that touches upon the topic of trauma often address: dysfunctional families (Hereditary (2018); Pearl (2023); Nitram (2021)); hidden problems of nuclear families (Raw (2016); The killing of a sacred deer (2017)); serious childhood traumas (rape, death of a close relative, abduction, etc.) (Possum (2018); The Boogeyman (2023); Smile (2022)); motherhood (Lamb, (2021)); queer discourse (They / them (2022)); criticism of capitalism and consumerism industries (Us, (2019); X (2023)); fem discourse and desexualization, gender (Midsommar (2019); VVitch (2015); Men (2022); Under the skin (2013)); race (Get out, (2017)); occupational trauma (Suspiria (2018); It Follows (2014)); collective trauma of the first level through the individual (for instance, wars) (A field in England (2013)); the feeling of worthlessness (Ritual (2017); Enemy (2013)).

So, "trauma horror movies" explore specific situations that fall into broader categories of collective experiences with distinctive characteristics. Jeffrey Alexander writes that the imprint of trauma breaks through the comfortable environment of bystanders who are not part of the specific group under consideration. For example, the collective experience of women in abusive relationships is expressed through the subject of the protagonist in Ari Aster’s movie "Midsommar," narrowing down to an individual but remaining collective, personified, and outwardly prevalent. The experience of "unloved children" can be easily read in one of the protagonists of Ari Aster’s movie "Hereditary" — the teenage boy Peter. "Get Out" by Jordan Peele captures the collective (internally psychological) experience of black people, narrowing it down to one hero, and through this narrowing, it presents a new semantic — the processed trauma encapsulated in time and visual form. «Imagination is intrinsic to the very process of representation. It seizes upon an inchoate experience from life, and forms it, through association, condensation, and aesthetic creation, into some specific shape. [6]»

When considering films in this subgenre, we can almost speak of Barthesian levels (sign — symbol — myth)[7] and structuralist systems:

1. The broad collective trauma of a specific group.

2. A specific hero or heroine personifying the trauma.

3. The "processing" of trauma and the emergence of a visual form that refers to collectivity.

Referring back to Alexander, it is worth noting that from the moment an event is represented within the imagination, an algorithm takes place in one’s head, which he calls the "trauma process": "(…) can be described by the triad: stabilization, confrontation, and integration of denied parts of the traumatic memory."

Horror movies of this subgenre serve the same function as Gestalt therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) since the 1980s: as a viewer, you exist in a constant state of possessing trauma while watching a horror movie that depicts the experience. It is precisely because of this maximum approximation that bystanders are included in the group by proxy. "While film does not provide an absolute decoding of the traumatic experience, this medium comes, in a way, close to this goal if only as a depiction of that which defies representation”. — Kabalek, Kohne and Elm.

Thus, in movies of this subgenre, a loop is created to represent traumatic events — "film thereby repeats and reenacts the experienced event, causing or actuating 'trauma' again and again on a cultural level — albeit in a transformed, mediatized manner. [8]" This same thesis resonates with Hannah Arendt’s theory of collective guilt and collective trauma, who writes about genocides and the Holocaust [9]: the constant repetition of traumatic events turns trauma into a characteristic marker within the consciousness of the entire group (in the cases mentioned above: the female experience, the experience of the "unloved child", the experience of people of color). Mimesis and diegesis (image + text in a broad Barthesian sense) create metaphors that change the epistemological foundation through which the event is perceived (reference). The philosophy of horror in Kierkegaard [10], based on the thesis that self-actualization requires facing death itself, i.e., one’s greatest phobia, the nightmare, already becomes a trauma that is postulated in principle in all horror films. It becomes maximally objective and relevant in the context of the aforementioned films — it is not just a confrontation with horror, but also a path, an escape from it.

In addition to this analytical foundation, of course, modern trauma horror movies use new codes that differ from "mainstream" and "classical" established traditions: a new type of work with sound, image, mise-en-scène, and scriptwriting of characters emerges. It is necessary to analyze several films of this subgenre to take a closer look at how trauma appears and manifests itself in the medium and with what means. Unfortunately, it will not be possible to touch upon every aspect and narrative variation in this work, and the analysis will be clearly incomplete, but it should be sufficient to understand the tools that directors use for "depicting undepictable."

Three horror movies will be analyzed and studied below: Hereditary and Midsommar by Ari Aster (2018), Men (2022) by Alex Garland; Additionally, mentioning A field in England (2013) by Ben Wheatley and Possum (2018) by Matthew Holness. Every analysis will be separated onto two small sub-chapters: hermeneutic ideological level of analysis + poetics as syntaxis of the text (in the sense of mise-en-scène).

“OUR FAMILY IS NORMAL”

Depiction of inherited traumas and an unloved child

Ideological level

Hereditary by Ari Aster is one of the first experimental horror films that delves into the theme of dysfunctional families and captures the psychological complexities and characters upon which they are built.

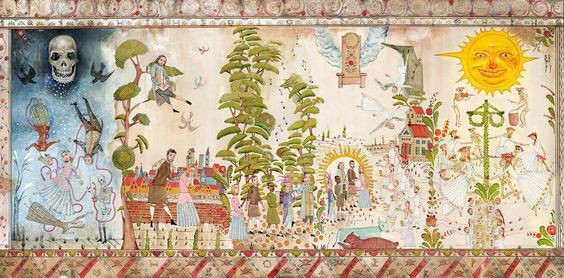

Annie is a talented artist who creates dollhouses. The very first shot from a distance frames her son Peter’s room as part of a dollhouse. In experimental trauma horrors, visual elements are always more important than in typical horror films. They help to construct the narrative piece by piece, gradually revealing an open ending that can be understood on a subjective and emotional level.

Subjectivity and open interpretation are crucial freedoms that the genre offers. There is no single correct explanation for any film, which is why the "experience" becomes personal, constructed from the viewer’s own interpretations and lived experiences that resonate with the characters. In Hereditary, many scenes serve as foreshadowing for the subsequent plot developments. From the beginning of the film, we see frames of children’s drawings depicting decapitated figures and shortly after, Annie’s daughter Charlie picks up a dead dove and decapitates it to make a doll. These visual elements immediately contribute to the conclusion, appearing right from the first shot: the dollhouse, everyone as puppets in the hands of the master artist, trapped in an endless cycle of reincarnation, their fates predetermined. In one scene, Peter is sitting in a literature class at school, discussing ancient Greek tragedies and the stories of Iphigenia and Oedipus, whose fates were predetermined from the very beginning.

By addressing these themes and incorporating symbolic visuals, Hereditary explores the deep-rooted traumas that shape individuals and families, ultimately delivering a haunting and thought-provoking horror experience.

The same thing is happening not only on a narrative level but also on an ideological level: the endless repetition of familial trauma, passed down from generation to generation. Annie’s mother suffered from mental illness, and Annie herself carries mentally unstable patterns of behavior. She has also experienced the trauma of her brother’s suicide and recently buried her mother. This hereditary mental characteristic is further passed on to both of her children. There seems to be no way out of this cycle, and, drawing on the occult leitmotivs present throughout the film, the ideological level expands not only to the thesis of trauma inheritance, but to the thesis of eternal repetition in reincarnations.

Psychological trauma becomes a twisted action — literally a loop, as mentioned earlier in the introduction [11]. The process becomes cyclical not only because of the plot or mise-en-scène, but thanks to the core of the movie — the main ideological dominant. If we break down "Hereditary" into hermeneutical analysis, the following overlapping of meanings emerges:

1. The story of a family in which a child dies; the experience of the trauma of a child’s death.

2. The story of a family in which mental illness is passed down from generation to generation.

3. The story of a family that is not only included in the endless transmission of "bad" heredity but also in the cycle of reincarnation through occult symbolism.

Moreover, "Hereditary" is certainly not only about objectively expressed trauma. One of the leading figures is the "disappointing child" or the revolting child, as Andrew Scahill [12] called it. The film has two child characters: Annie’s daughter, Charlie, who inherits supernatural abilities from her grandmother ("the alien kid"), and her son, Peter, who is a regular teenager going through a difficult stage of adolescence ("the revolting kid") — the eldest child in the family, whom the mother practically ignores because she gives all her love to her younger daughter.

The phenomenon of demonizing a child who does not conform to socially established norms of a "good child" typically occurs during adolescence, as hormonal imbalances and the beginning of self-actualization and separation as individuals take place. The "bad child" — the demonized child — poses a threat to the hetero-nuclear (nuclear) family, where it is expected that the child inherits all the best from the parents, including habits and character traits. In this sense, Peter is a demonized child, on whom the mother projects all the blame. The well-known scene with the dialogue "I am your mother" [13] demonstrates the truly horrific relationship in the film, excluding all paranormal phenomena: the boy almost starts crying, while the mother screams at him at the peak of a nervous breakdown.

There is a split in the plot element: the younger child, Charlie, who literally becomes the carrier of a demonic entity, is deified by the mother, while Peter becomes the "demonized child". The tradition of depicting a "special child" in horror films is reversed — the "special" child dies and is replaced by a completely ordinary teenager, onto whom this role is literally transferred. "As with "revolting children," a consideration of "consuming futurity" recalls both the threatening object (a future that consumes the present) and the act that attempts to negate that threat (controlling children as a means of determining the future)." — here, another rift occurs: in her attempt to control the older child, Annie only gets deeper into the inevitability of fate — a predetermined future in a parental understanding cannot exist from the beginning.

The child troubles the family with their troubling incompatibility, but there is no outside the family.

Poetics

Trauma horror films work with space differently from classic horror films: firstly, sound is almost always handled without the use of "trigger sounds" — loud vibrations, screams, slamming doors, etc. There is still work with uncanny sounds that trigger the mind, but now these sounds are mostly presented in the musical background, specifically tailored to the film’s motifs. Colin Stetson composed the music for "Hereditary," building the compositions almost entirely based on wind instruments and vocals — resulting in an arrangement that enhances the viewer’s perception of the film’s conceptual level through associations with occult and spiritual sounds: “Cinematic sound often operates on our subconscious. [14]”

At the same time, there is a play of light: abrupt changes between day and night, the emergence of "demonic light" in the shots, transitions from extremely bright tones to extremely dark tones (the scene with the severed head on the road). Ari Aster uses several main shots in "Hereditary": the long shot — the room — a dollhouse; the close-up — the face — the emotion, the psychology of the character; the medium shot — dialogue. Camera angles vary from scene to scene, but towards the end of the film, almost all the shots are taken from a "Hitchcockian" perspective — the camera is positioned below the actor and captures everything above their head (in the case of this particular movie — the ceiling and attic). The synesthesia of sound and visual elements shapes the entire chronotope of the house, but it is not a pleasant, prosperous dwelling, but an eerie space.

Crucial worth-mentioning interior detail in "Hereditary" — a model of a dollhouse made according to the prototype of Annie’s own house: it goes deep underground, connected to the scene of her mother’s funeral; the house is multi-layered, tuning floors to floors, creating continuity even in the space itself. The characters in the film constantly move between two floors, and closer to the end, a third attic floor is revealed to them: it is not just a physical, but a psychological and spiritual "elevation". In the final scene, Peter climbs up the stairs to the treehouse where Charlie used to play — a spiritual ascent is carried out solely with the help of demonic, otherworldly forces that reside in both of Annie’s children. The last scene is theatricality of wax figures [15].

“I AM SAFE WITH THEM. AM I?”

Female fears and insecurities as a trauma threshold

Ideological level

When it comes to discussing traumatic collective experiences, the discourse always turns to the fact that society still upholds the image of a Kantian man from the Enlightenment era — a white heterosexual man, well-established and educated, at the top of the financial ladder. People of color, queer individuals, and politically repressed groups are not taken into account — just like women.

Aster’s "Midsommar" and Garland’s "Men" are psychological portraits of experiencing collective trauma from a female perspective through the individualized experiences of the main heroines. Of course, to explore such a topic, it would be desirable to consider the female gaze and a feminist optic in filmmaking, but here we will focus only on these two A24 films due to their mass circulation and greater recognition compared to those of "underground" female horror directors with a feminist perspective.

A woman living in a phallocentric society [16] inevitably experiences some form of violence, whether physical or psychological. This can be related to abusive relationships, demands for childbirth, difficult family situations arising from nonconformity (such as in cases of strong religious beliefs), and the infringement of personal identity and dignity. On a physical level, this includes beatings, rape, painful menstruation, and psychologically and physically traumatic childbirth. Men hold the power and control over women’s bodies, implementing a repressive mechanism, including the political subjugation [17] of women.

The main heroine of "Midsommar" — Dani — experiences the death of her parents and seeks support from her boyfriend, Christian, with whom she is in a psychologically repressive and abusive relationship that completely ignores her as a human individual. The protagonist in "Men" witnesses the death of her own husband, who jumps out of a window (it is unclear whether intentionally or by accident) after a serious conflict with her. He emotionally manipulated her by saying that he would commit suicide by jumping.

Both heroines find themselves in isolated environments, far away from society — to put it bluntly, both end up in rural areas far from the city, in unfamiliar territory — a "no man’s land" surrounded by "wrong" people.

"Midsommar" explores the theme of female repression not only within abusive relationships with men (the main character’s boyfriend ignores her emotional state, disregards her as a person, and fails to provide any support, while also wanting to break up for a long time), but also the overall existence of the female subject in a phallocentric world, ignored by others. Dani (Florence Pugh) is not the most conventionally attractive girl, and throughout the first half of the film, men ignore her, leave the room when she appears, and don’t even remember her name when they meet. The main heroine ends up in a Swedish community together with her boyfriend and his classmates, who have come there to gather material for their anthropology PhD dissertations. The traditional old religion-based community, built on Scandinavian totemism and sacrifices, is immediately perceived by the viewer as a cult, first of all, due to the musical and visual design, which will be discussed below; the extraordinary, disturbing friendliness of some characters towards Dani, contrasting with the general attitude towards her; and the unconscious connection of the setting with early folk horror films — the cult-like aesthetics and rituals are felt even if the viewer is not familiar with "The Wicker Man" (1973).

The community accepts the main character as the new May Queen, surrounding her with care and warmth — becoming her new family, replacing her deceased parents and overshadowing the negative effects of her interactions with Christian. It’s not just Dani becoming a part of the community, but the community becoming a part of her — on a collective level: the refrain of crying, embedded in the chorus at the beginning of the film (Dani mourns her deceased parents) and closer to the end (Dani mourns her boyfriend’s cheating) — these are the culminating points that shape the narrative. The "liberation" from male influence happens right after the second act of crying — the closure of the refrain / chorus: at the beginning of the film, Dani cried on her knees with Christian, who was unable to support her, and in the second part of the chorus — in a huge group of girls, merging their voices into an exhausted scream.

The final scenes of the film — the burning of the yellow ritual pyre and the mass sacrifice, in which the main character’s will plays a role — represent a total experience of trauma through the destruction of its origin. Dani becomes the "queen" in a floral costume, while her past burns, and the members of the community bid farewell to it in catharsis. The individual traumatic experience of the heroine, which goes beyond the death of her parents, becomes encapsulated in a myth of female liberation. The woman at the end of the film is portrayed not as a passive patient, but as an active agent — she makes a decision that brings her happiness [18]. Here, of course, the discourse of the cult’s influence on a person’s consciousness unfolds, but the basic level of analyzing trauma in "Midsommar" is precisely the burning of the past: subsequent films in the subgenre will adopt the same narrative structure ("Smile" 2022 — the main character burns down her house, leaving trauma from her experience with her mother’s death behind).

"Men" is also a film about the disruption of the gestalt due to emotional manipulation by a partner, as in "Midsommar". Harper, the main character (Jessie Buckley), travels to a remote village, renting a small cottage to spend time alone and psychologically recover from what she has experienced: her partner, in a fit of anger during a conflict with her, vows to end his life by jumping out of a window, leaving Harper unsure whether it was intentional or a coincidence. Finding herself in the enclosed space of the forest, Harper begins to be pursued by strange men — in the opening scene of the film, a naked unknown man follows her through the woods and doesn’t relent until she runs back into the house [19]. The pursuit then becomes psychological — she is afraid to be in a place where only men live, of different ages and social classes: a teenager, a middle-aged priest, overly friendly supporting characters from the tavern.

The forest is an archetype of the unconscious in world culture, necessary to overcome boundaries (see Dante and the roots of jungian psychoanalysis relying on cultural codes): in the forest, one can easily get lost; the forest is a battlefield between reason and the irrational, in this case, fears and dreams [20]. Several times throughout the film, the chronotope is disrupted, and Harper is retrospectively brought back to the moment of her partner’s fall — she enters the cyclical confinement of her consciousness, literally into the "forest" of her mind, from which she needs to escape in order to experience the trauma in its most primal sense — the feeling of vulnerability and constant vigilance of a lone woman in the group of men.

Poetics

Analyzing these two movies, attention should be paid to the color palette, the painting of the images, and the synesthesia of sound and color, first and foremost.

In "Midsommar," all the landscapes become eerie precisely because they shouldn’t be inherently frightening: the sky is clear and bright, greenery abounds. The cinematographer works with wide shots and depth of field to capture people merging with nature on a communal level. The sense of "midday horror" emerges for the viewer closer to the middle of the film when the extremely vibrant and contrasted color palette starts to dilute the white-green tones while merging with synesthetic musical accompaniment that emphasizes soprano voices and ritualistic chants. The hallucinogenic effects of the mushrooms consumed by the commune, subtly incorporated into the landscape backgrounds and likely to go unnoticed during a casual first viewing, create an even more absurd and non-rational field.

"Men" plays with extreme tonalities, abruptly shifting to dominant red hues in retrospective scenes, simple color associations ("red — blood"), becoming emerald green in natural scenes, and white-gray in the church. Towards the end of the film, practically all of the color design is reduced to black tones. The only exception is the main character’s cottage, which becomes a "refuge" and a shelter from the aggressive invasion of excessive light.

Additional: Individual traumatic experience: war and childhood trauma

A very small number of horror films explore the theme of collective-individual military trauma. Usually, this task falls upon psychological thrillers ("Jacob’s Ladder" (1990)) or dramas. "A Field in England" (2013) by Ben Wheatley appears to be almost the only experimental horror film on this topic. Moreover, both the narrative and the film’s form are compositionally constructed according to unconventional measures of classic horror films.

A group of English soldiers find themselves in an infinite field that becomes a "purgatory" for them. They cannot escape this space, time twists and stretches, and the chronotope disintegrates with each new scene. "A Field in England", unlike all the other mentioned films, is filled with postmodern expressions and is generally built on theatrical principles. The characters seem like a single "troupe" performing endless funny sketches, slowly transforming into absurd horror. The occult symbolism of the "black sun" from the world Kabbalistic tradition, the framing of shots with a dichotomy between earth and sky, the blurring of the boundary between life and death [21] — it all becomes a representation of the internal post-traumatic stress syndrome that emerges in a person after war, something incomprehensible. An event that once "did not exist" but, through its act, destroyed the imaginary and created trauma as such, as Jeffrey Alexander puts it [22].

The experience of a childhood trauma of abduction in the film "Possum" (2018) is predominantly resolved visually rather than narratively. The film lacks a conventional plot, but there is a storyline that is deciphered not through an explicit ending, as experimental films of the genre often do, but through the overall openness of the plot and symbolism for interpretation. The enormous spider [23] becomes the embodiment of childhood horror (a similarly large spider appears in the movie "Enemy" (2013)). "Game-like" space with almost complete absence of dialogue, where the plot is built through hooks and allusions, constant movement of the hero through an empty house and outside, deconstructs narrative lines, leaving only elements.

***

“The aim is to restore collective psychological health by lifting societal repression and restoring memory. (…) Some collective means for undoing repression and allowing the pent-up emotions of loss and mourning to be expressed.” — Cathy Caruth is quoted by Jeffrey Alexander in the context of examining the sociological phenomenon of trauma.

So, within experimental contemporary horror films, one can identify a separate subgenre, not yet fully substantiated and named, namely the aesthetics of "liberating" films that capture psychological traumas, that can be traced back to the emergence of the catharsis tradition in Ancient Greek theater. For the films discussed above, as well as for all the mentioned ones, which would be useful to consider in a more comprehensive work, "catharsis" can be seen as the primary impression. But, beyond that, it is not just a cathartic expression of emotion, but an experience ("experience" as the infinite repetition of a single piece of the past and "experience" as an emotion) in which the viewer involuntarily becomes involved.

Through a specific construction of visual syntax — compositions of frames, camera angles, literary-cinematic tropes (refrains, catachresis, metaphorical and allegorical leitmotifs), color schemes, soundtracks, synesthesia of all the aforementioned elements, as well as the narrative canvas, which only complements the ideational level but doesn’t fully constitute it (as is the case in classical horrors) — the maximum connection between the individual subjectivity of the viewer and the individual subjectivity of the hero or heroine is achieved, thus resulting in the collectivization of consciousness. "I am very much like you, and it makes me feel bad."

NOTES

[1] Robin Van den Akker, Metamodermism: historicity, affect, and depth (2019)

[2] “ [It is] a style of thought which is suspicious of classical notions of truth, reason, identity and objectivity, of the idea of universal progress or emancipation, of single frameworks, grand narratives or ultimate grounds of explanation.” — Terry Eagleton, The Illusion of Postmodernism, 1996

[3] The horrors of trauma in cinema: Violence Void Visualization, Michael Elm, Kobi Kabalek and Julia B. Köhne (2014)

[4] Jeffrey Alexander, Trauma: A social Theory (2012)

[5] Elm, Kabalek, Kohne

[6] Jeffrey Alexander, as mentioned above

[7] Rolan Barthes, Mythologies, 1957

[8] Kabalek, Elm, Kohne

[9] On Violence, Hannah Arendt, 1970

[10] Fear and trembling, Søren Kierkegaard, 1843

[11] Hannah Arendt

[12] Youth Rebellion and Queer Spectatorship, Andrew Scahill, 2015

[13]www.youtube.com/watch? v=dUdi3×2vGLo& pp=ygUdaSBhbSB5b3VyIG1vdGhlciAgaGVyZWRpdGFyeSA%3D

[14] Blumstein, Daniel T., Gregory A. Bryant, Peter Kaye “The sound of arousal in music is context-dependent.” Biology letters 2012

[15] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z317bw_0zdI&pp=ygUXaGVyZWRpdGFyeSBmaW5hbCBzY2VuZSA%3D

[16] New Blood in Contemporary Cinema: Women directors and poetics of horror, Patricia Pisters, 2020

[17] Manifesto contrasexual, Paul B. Preciado, (2000)

[18] www.youtube.com/watch? v=x2ABJAyfVpw& pp=ygUZbWlkc29tbWFyIHRoZSBsYXN0IHNjZW5lIA%3D%3D

[19] www.youtube.com/watch? v=Vr8yotBSWbg& pp=ygUhZm9sbG93aW5nIGluIHRoZSBtZW4gbW92aWUgc2NlbmUg

[20] Carl Jung, Archetypes of the unconsciousness + A dictionary of Symbols, Juan E. Cirlot 1958

[21] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bvHc5KYwRO0&pp=ygUZYSBmaWVsZCBpbiBlbmdsYW5kIHNjZW5lIA%3D%3D

[22] “Imagination is intrinsic to the very process of representation. It seizes upon an inchoate experience from life, and forms it, through association, condensation, and aesthetic creation, into some specific shape.” J. A. Trauma A social Theory

[23] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YlAlDLHF4Q8&pp=ygUUcG9zc3VtIHNwaWRlciBzY2VuZSA%3D