Sentences on Jasper Johns

••••

If Jasper Johns is a philosopher-king of modern art, he is one in seclusion — an archetype of a statesman who, upon retirement, leaves for the countryside, tends to the garden and works the plow. Nauman is similar, and it’s telling that the two are almost of the same generation.

••••

All art that is heavy with references makes the viewer ask themselves what is it exactly they need to know before they approach it. It’s a ghost that haunts those hesitant to pick up Joyce, missing out on the self-sufficiency of the work. Similarly, Johns is most approachable at the exact level you already have on your first encounter.

••••

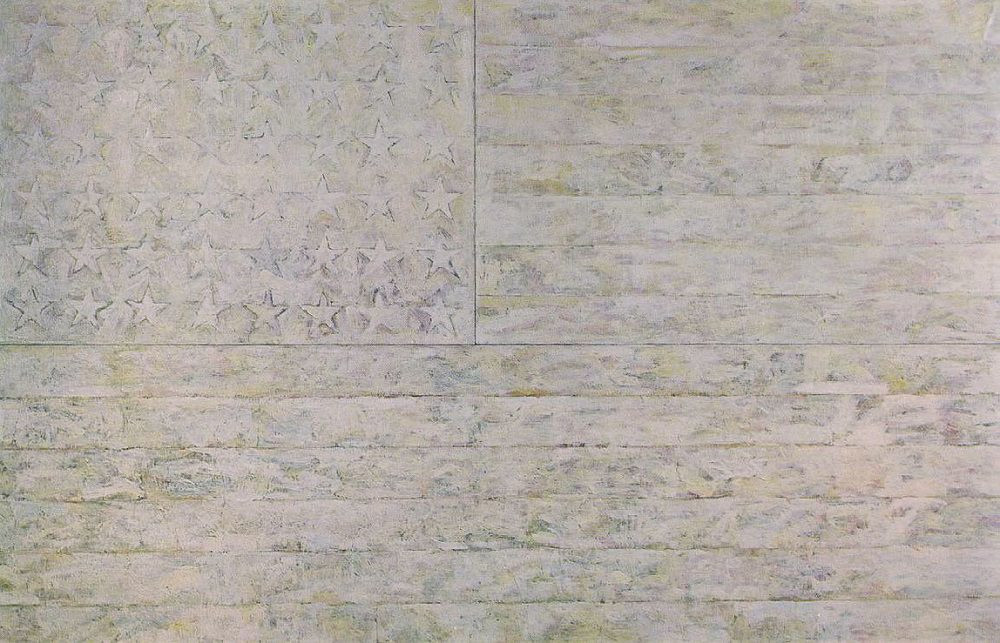

Johns being known as the flag painter, one of the bronze-cast flags even gifted to Kennedy on the Flag day, no less — only shows how popularity is inseparable from instrumentalizing: it contains little to nothing of the work itself.

••••

Drawing numbers for 50 years must induce some sort of relationship with them, at the very least from all the failures and successes. But how does he actually go about it? “I should probably do a 3, it’s been months.”

••••

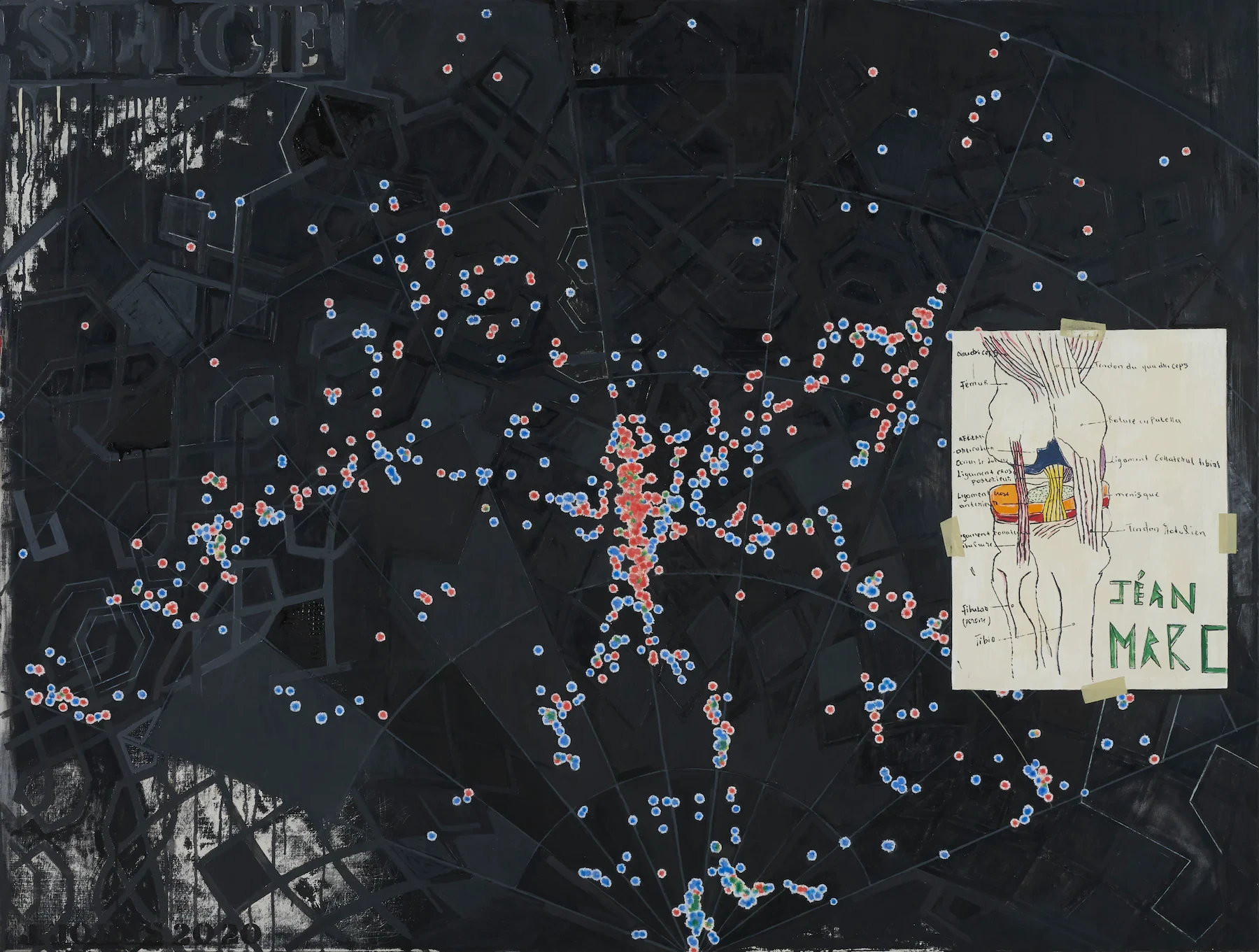

So much of late Johns’ work is genre: memento mori, the seasons, the still life, and, I suppose, cartography here is landscape.

••••

At the Philadelphia museum, Johns’ show is accompanied by a locked storage section, right there in the exhibition hallway, providing a quick rotation of prints in the next room, each, oddly, having an inventory tag on the wall beside it, last-night-before-auction-style, sort of. The sheer volume of repetition is problematic.

••••

Encaustic means that paintings can never be in direct sunlight. It allows one to work fast and deliberately, but dooms the work to be eternally fragile, a conservator’s nightmare similar to Cy Twombly’s crayon works or Matisse’s glued paper. Unlike them, Johns has little to excuse himself with, the habit probably at least partly born of impatience, and only turned into a systemic approach over time. A weakness persistent until it’s style.

••••

‘Metaphysics’ is probably a good word to describe Johns when he is not dabbling in symbolism. In a literal sense — study after the study of matter, where matter is just whatever the things are made of.

••••

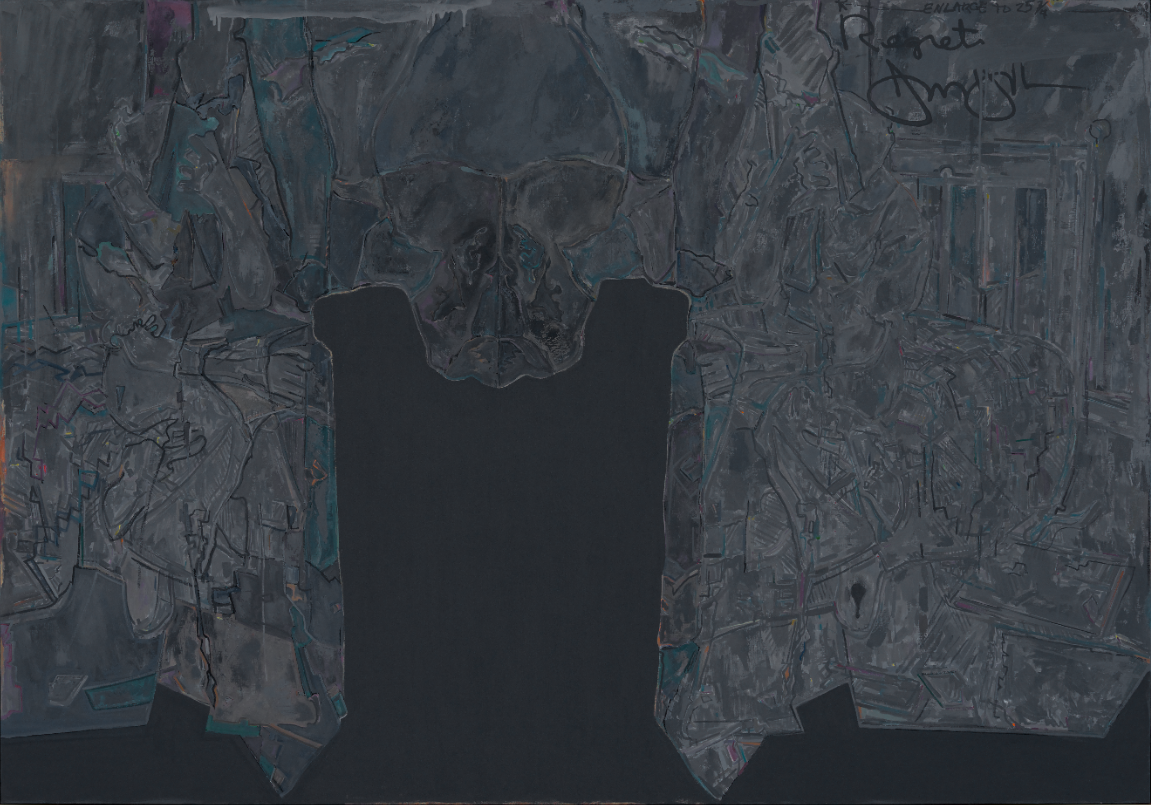

The human is most multifaceted in Johns’ work: a stick figure, a fashionable skeleton, a bunch of wax-cast disemboweled limbs, an outline of his own shadow, a Mona Lisa. Compared to all the ways of the human, the M101 galaxy, also recurring, enjoys an enviable stability.

••••

Johns is not completely detached from his sources, but seems to hold them at a great distance. When one finds a repeating pattern, it may be tempting to hunt down the original and perhaps the piece where it was used first — but one also acknowledges it is not an essential task; it will not really solve the work. Nothing will happen if you find out.

••••

Johns uses the preexistent, but only once it’s internalized. In the raw, a preexistent is not even a potential future part, it’s not anything at all.

••••

Cecily Brown says Johns was miscast as a mysterious artist. It’s true in the sense that we often seek mystery in the wrong place. The true gap is the fact that we too don’t really know how skulls, galaxies and floorplans come together in the grand scheme of things.

••••

Savarin Monotypes are just bad. They’re not pop art — although they are about liking things.

••••

On the classificatory note — nothing about Johns is pop art. His need for reworking is born of curiosity and maybe some lack of foresight, not the theme of mechanical reproduction. The flag and the targets are born of conceptualism and the Wittgenstein fever of the 1960s', coupled heavily with abstract expressionism as, in this case, a native tongue.

••••

Rothko reportedly disdained Johns’ use of symbols. “We worked for years to get rid of all that.” One can sympathize, but also note how Johns did not step back into the representational as much as carried these things over into the abstract-expressionist fold.

••••

Johns is probably not interested in the topics his objects usually stand for. The duck-rabbit illusion is at home here: once you see the other half, it’s no longer either/or.

••••

Johns’ sculpture feels like something he couldn’t quite fit into the 2.5 dimensions mounted on the wall, many objects eventually reborn as their own outlines (including the man himself). Coupled with the monochromatic, painterly treatments of the sculptures, the place of objects in this corpus is telling: they are better off as images.

••••

When it comes to “biography”, Johns sort of met Leo Castelli in ‘58, and now lives in Connecticut in a large estate that will apparently serve as an artists’ retreat after his death. Things happened in between, but as far as the common narrative goes, they might as well have not. Before the double retrospective opened in 2021, it was normal for people to be surprised he was still alive.

••••

Unsurprisingly, Johns and Rauschenberg make for a great comparative study. It is through Rauschenberg and his use of images in showing a changing world that we see that Johns’ world isn’t changing.

••••

Thematic accumulation is the one thing that’s very hard to relate to in Johns’ work — it runs counterintuitive to what we’re used to in personal growth. For everyone else, themes from twenty years back may enter once more by way of a self-allusion, or not at all. With Johns, it’s almost like they are objects of a higher order, imperishable from the world.

••••

Nauman did take a lot from Johns: typography and body parts and doubling, among other things. The way, unlike Rauschenberg, the two don’t feel like a great comparative study, is itself something worthy of exploration.

••••

Dream series can be appreciated just for how wacky it is. It’s important for an otherwise stark, intellectual and elegiac artist to have the wacky somewhere in there as a great balancing act.

••••

It’s odd for an intellectual artist, known to have plainly stated his work does not represent his feelings, to be essentially private. One can’t imagine John Cage sitting at home, playing 4’33” to himself. Perhaps Johns’ work is sensual in some way that just doesn’t really overlap with how ‘sensual’ works in others.

••••

Johns—Munch connection is curious. Both have spent much of their lives working away from art capitals, in the seclusion of rural homes. Johns shows Munch’s influence, both in his renditions of space and the brushwork. Museum staff even found Munch’s bedspread that gave Johns the crosshatch motif. Still, it is strange that Johns would be preoccupied with Munch, who was probably most preoccupied with himself.

••••

Given the above, it is entirely possible to read Johns’ work as sensual, and why not.

••••

There exists, undoubtedly, a surface interpretation of Johns: of images either flowing or stagnant in shallow waters, of linkages meaningless and unfulfilling. Importantly, there exists just that reading of the cosmos as well.

••••

Johns will turn 92 this year. I am glad he lived long enough to produce so much work. I am glad he witnessed his double retrospective, regardless of how much it means for him exactly. With him, a significant personal observation will be gone from the world.