A conversation that can happen at any moment (with you as well)

On February 24, 2022, russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The war has been going on for almost a year, during which, according to the UN report published on January 13, 2023, more than 7 thousand civilians were killed in Ukraine[1]. The war comes with the destruction of civil infrastructure, including power plants, which leads to regular power and heat outages that all residents of Ukraine experience.

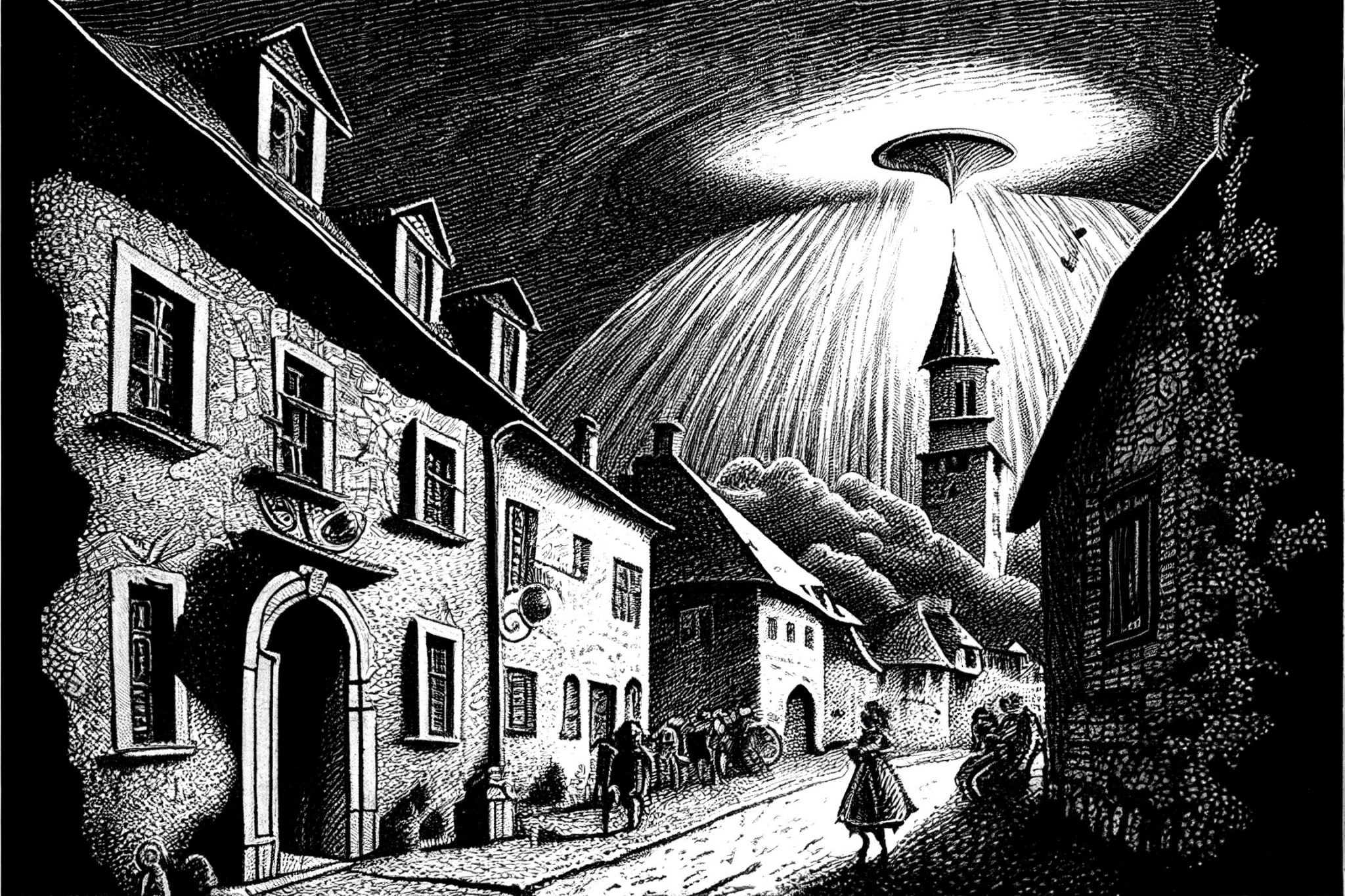

Researcher and artist Ruthia Jenrbekova turns to her friend, writer Galina Rymbu, who lives with her family in Lviv, to talk about nomadism, broken ties, and the work of the imagination during the war. Due to constant power outages, this conversation breaks off and takes on an imaginary form, where the conversations that took place are mixed with fragments of the texts of both participants.

The text was written in November—December 2022 and was first published on the typography-worldwide.org

Ruth: I’ve wanted to talk to you for a long time, but I don’t know how to. Even now, when this conversation is being supported and published, there’s no service. And if we managed to get through, what kind of conversation could we have? Here is my first (first?) question for you. Too bad you can’t hear it.

Galya: I can’t hear you! We have emergency shutdowns.

Ruth: Okay, what conversation could we not have?

Galya(silent)

Ruth: Do you agree that a failed conversation is also a conversation of a kind?

Galya: I’m so happy to hear you! Of course, I agree. It’s just a matter of understanding when and how (it did not take place). We are currently having emergency power outages, I think they will continue in the next couple of days. During this time, it will be impossible to predict when I will have electricity and the Internet and when not. Today the power got back on only a couple of hours ago. Write to me when you’re available to talk, the Ukrainian power lines and I will try to adjust 🙂 I have Zoom and Skype, and both work fine when there is Internet. But we can also talk through texts if it’s convenient.

Ruth: My thoughts are with all your heating and power lines, including your personal blood-vascular heating networks and neural electric grids! 🙂 Let’s set a day, and if it doesn’t work out, we’ll set another one? Let’s say December 3 or 4 — what do you think? And what time of day and night is best? Perhaps we will decide that one time is not enough, or on the contrary, too much. I’ll think about hearths — and about networks, networks connected to hearths! — and in the meantime, you can look at the Google doc. And then write to me as soon as possible! And I will write to you. Tomorrow!

Galya: Good!

Ruth: Look now, tomorrow has come, and with it, new missile attacks on the cities of Ukraine. A conversation that is interrupting, is it still a conversation? What may one (as in — what is appropriate, acceptable) talk about with those whose cities are now bombed by Russian missiles? How to ask about the feeling of being at Home when looking at photos of destroyed houses? What questions could I come up with, except: are you alive? Are your arms-legs-heads intact, is your neighborhood intact, do you have food, water, light, heat, medicines? How many degrees of heat are still in your house?

I don’t know where to start: you are now in a situation that is incomprehensible for people like me who have never experienced anything like this. Therefore, I feel all the words addressed to you as inappropriate, inadequate, and my second question would be: can we allow ourselves to speak as if disregarding reality, ignoring or actively pushing it out of sight? I feel like I’ve always tried to do it this way — hence the inescapable feeling of my own not-quite-adequacy. Like the Dutch artist Renzo Martens, who asked the victims of the war in Chechnya questions like “what do you think of me? how attractive am I?” etc[2]. Or that speleologist from Cortazar’s story, who, while making a dangerous descent into a cave in order to study it, for some reason focuses on studying the contents of his bag and makes an important discovery: instead of cheese sandwiches, they gave him ham[3]!

Galya: I write so that I can eat cheese.

Ruth: That’s right, you do that too — deny the reality the right to dictate us its terms — when you write cyberpunk texts about new species emerging from ruins and underground milk; about devices made of fire and the secret library of book beings; about queer human angels and butch-panda; about wandering street animal universities and thousand-year-old computers of the forest. Life’s circumstances try to make fantasies meaningless because circumstances are always stronger, but fantasies don’t give up easily! Creativity must be somehow linked with this stubborn unwillingness to submit to whatever is stronger than you, with a rebellion against reality “as it really is”. I wonder when this discrepancy with reality is no longer a cognitive defect, inadequacy, or a joke, but the only right decision — in a situation where it would seem that there can be no right decisions. However, sometimes fantasies refuse to work.

Like right now: I don’t understand where you are, I just can’t imagine. Am I talking to you or to myself? Our realities were similar but became so different. What kind of conversation would make sense to you now — where you are?

Galya: Not everything makes sense. War doesn’t make sense.

Ruth: Did you actually say that?

Galya(silent)

Ruth: Broken ties — a leitmotif that haunts me. Connections that were preserved so carefully and safely in childhood and began to slowly break in adolescence — but the further — the more, faster, more disastrous. Are you familiar with this? It’s a sobering experience — to discover one day that there’s nothing holding you back. This feeling is not so much of freedom as non-existence. In fact, there are no Creoles in Kazakhstan (refer to the population census, haha), there’s no person named Ruthia Jenrbekova either, and never has been. That’s the official version, confirmed by documents. I arose as an alternative to this version — as a fake or apocrypha. To somehow justify the right of this alternative to exist, you need textual documents, for example, poetry. I think, in this sense, your recent “Constitutions” are very important: they are the apocrypha of a new reality that takes on flesh following the logic of new texts. They confront the old constitutions that are still in effect, they even insult the old texts — this so-called canon, this weaving in the heads, firmware…

Galya: Of course, insulting the authority and undermining its foundations is our direct action, we — the ones who write, destroy…

Ruth: Exactly!

Galya: Especially in writing free from ideologies (as far as it is possible?)

Ruth: That’s why — in search of a firmware for my own existence — I once translated a chapter from a famous book by Édouard Glissant — a book that describes the Caribbean experience as if it was Central Asian or global. The chapter was called “Errantry, Exile” and began with the words: “Roots make the commonality of errantry and exile, for in both instances roots are lacking. We must begin with that.”[4] In other words, we must start with the fact that there is nothing to start with. Maybe it’s a good thing to start from this fundamental loss because it would mean that we would probably gain something in return towards the end? But what? What can a break in the connection, which was defining for you, give you?

Galya: The birth of a new being?

Ruth: Excuse me? What did you say?

Galya(silent)

Ruth: Galya, I know you’re here, although you’re obviously not. In physics, there is a concept — non-locality [5] which seems to reflect the inexplicable and, therefore, exhilarating properties of reality. After non-locality, I discovered a (also Creole, in fact) term “translocality” — a shibboleth of all migrants and nomads (I must say that with everything beginning with “trans-“, especially the names of transport companies, we find amusement in automatically including them in the virtual trans*community). I would also ask you about your transitions: from Omsk to Moscow, then to St. Petersburg, then to Lviv — how easy and hard were they?

Galya: And to you?

Ruth: I once considered myself such a nomad, I liked what Rosie Braidotti says about nomadic feminism — a nomad as an exile, a migrant, but at the same time a traveler, a discoverer of new spaces [6]. You know, nomadism can be real — like the Kazakhs, and can be from books, like in Deleuze. But historically (and this is reflected in the etymology of this ethnonym), Kazakh nomadism, just like Deleuzian nomadism, was also an attempt to get away from sovereign’s control, from vassal relations with the empire or khanate. That is why nomadism is always associated with the duality of exile-punishment and wandering-adventure and with the possibility of one turning into the other. All the worst (for example, someone locked you in a room) can always become the best (you embark on the most exciting of journeys — around your own room, like Xavier de Maistre). Or the same in Glissant: in the chapter “The Open Boat”, the slave ship, designed to transport slaves, is transformed into a boat of wandering, connecting humanity within one whole earthly world. Right now, I am reading about the same thing by Sergei Abashin: “… the word ‘ark’ […] indicates extreme danger, but it also indicates the way of salvation.” Travel can be anything: celebration and mundanity, work and slave labor; it can come out of both excessive wealth (I don’t know where to go: there’s a place for me everywhere) and extreme poverty (I don’t know where to go: there’s no place for me anywhere).

But my whole life, I have lived in Almaty and mostly journeyed to the edge of the world on the couch. It seems that my fascination with everything distant comes from this quiescence. When you’re not leaving the house for a long time (for example, because of fear), then the landscape outside your window begins to move slowly by itself. And suddenly you don’t know where you are anymore. Now, in every text, you insist on the importance of imaginary things because you want your sofa and yourself to be taken seriously. It may even come to conversations with imaginary confidants. When I write poetry…

Galya: … I am never alone: there are always communities around me, classes, even my friends, close people, their speech, it seems as if I answer them as if I speak “here and now”. But poetry is a place where one must constantly be disappointed in one’s own presence and in the presence of another in order to assure oneself of it, once again, on new grounds.

Ruth: I don’t know how it would be possible to assure oneself of anything at the moment — we are rather delving into the metaphysics of absence — into this strange attempt to equate what supposedly does not exist with what supposedly exists. Everything becomes unreliable here.

Galya: Life in a limited space: so any space is unreliable

Ruth: At the same time, the space of imagination seems to be unlimited! It is our only weapon in the battle with reality, as I think Jules de Gaultier has said. Don’t you agree? Take, for example, translocal nomadic feminism — isn’t it a rebellion against what actually exists?

But what actually exists? What do you have there now?

Galya: Us? We now have electricity eight hours a day, the rest of the time it is dark and cold, and the Internet also does not work without electricity (I have a router).

During these eight hours, I try to do everything possible: cook warm food for my son, give him treatment (he got sick from the cold in the house), clean up after cats and so on, run to the store and pharmacy… In short, all these eight hours with electricity are spent on taking care of the house (I now take care of everything alone since my partner’s depression has gotten worse, and it’s now difficult for him to move around). I don’t know how we could synchronize. It’s especially hard because we don’t know exactly when these hours in the day will come when there will be light; we might just be asleep at this time; they turn it on twice a day, each time for four hours. I can try to trace the pattern of switching on/off and arrange to call you tomorrow or the day after tomorrow. But I apologise in advance if my light is off at this time.

Ruth(silent)

Galya: Hi! Why are you silent? We’ve had electricity for almost a day now! Today I even managed to take my son to school. I want to write answers to your letters and remarks that you sent by email, we could at least talk like that, in letters. You asked about another messenger — I use Telegram, if you want, we can continue the conversation there. I like the idea of a collage. But let’s see what comes out of my answers to those first letters and from your answers to these answers. They’ll be ready before the end of the day. And you, of course, can take any answer or text and just comment, but then I also want to comment on your texts! If we support this format.

Ruth: Yes, yes, we support — mentally — all formats, as well as the ZSU [7], each other, and this conversation, which, in turn, supports us. I observe how things that were mute for the time being suddenly become our topics: they gain visibility, change shape, acquire, and then lose their meaning again. Words behave in exactly the same way — they acquire and lose their meanings because words are also things, just like things are also always signs for something else (this is an important point of the so-called material semiotics of Donna Haraway). I would like to choose for our topic something far from reality, hide from the danger of a direct collision with it, ask you questions about other worlds (matters of the future world, as you say), about some undiscovered creatures, about animals and plants and other persons, about how poetry, the Constitution and other literary genres are connected, ask about the borderlands of Gloria Anzaldúa and about the carrier bag theory of Ursula Le Guin, and about infinitely more other things. But I can’t. And you will not answer. And if you do, it will most likely be the answer to a completely different question. As Yevgenia Belorusets writes in her “War Diary”: “I asked him what he sees around him. I wanted to know how this lazy, slow, melancholic southern city deals with the constant rocket fire. He said, as if answering a completely different question, that war is terrible and not romantic, that no book he has ever read has described what is happening there now.”

Galya: But it is not enough to stand on the opposite river bank, shouting questions

Ruth: The side is always either this one or the other, it is absurd to talk about the third side of the river…

Galya: At some point, on our way to a new consciousness, we will have to leave the opposite bank, the split between the two mortal combatants somehow healed so that we are on both shores at once and, at once, see through serpent and eagle eyes. Or perhaps we will decide to disengage from the dominant culture, write it off altogether as a lost cause, and cross the border into a wholly new and separate territory. Or we might go another route.

Ruth: These are quotes from Gloria Anzaldúa! This is totally our Central Asian theme — the new consciousness of the mestiza. I didn’t know that you read her work too, why didn’t you write earlier…

Galya: I’m sorry I didn’t write earlier! I can’t meet this deadline. We still have problems with light, heat, and Internet. It’s cold at home, and I got very sick from hypothermia, my kidneys became inflamed, and I’m just now starting to recover under a shock dose of antibiotics after I managed to lower my body temperature a little. Maybe there is an opportunity to ask the organisers for a few more days for our dialogue, given the extreme circumstances that do not synchronise with the emergency deadlines? Do you think there is such a possibility?

Ruth: Wait, don’t disappear, I’ll find out now…

Galya: …I think we might have been living on some other planet’s orbit for a while now, and the whole Oktyabrsky district has moved there.

Ruth: Those were my words! I grew up there, in the “Orbita” micro-district! You see what I’m doing — I’m trying to talk with a sick friend who lives cut out from communication, light, and heat in a country attacked by the rashist army! — about what? Other planets. Is this the right way to show solidarity?

Galya: Each one will create their own life as they wish. Each one will create an Institute for Earth’s Conditions.

Ruth: I put these words into your mouth so that they sound like little prophecies.

Galya: Each of us speaks for herself — always just of herself. And always with somebody else’s words.

Ruth: I don’t know, it’s embarrassing to make you a character in my own play.

Galya: It’s okay. I allow — make a character out of me. What do you feel when you put words into my mouth?

Ruth: The feeling is shame. I am a woman who is ashamed to say “I”. Pansexual, a person with a high content of male hormones.

Galya: It looks like you’re quoting me!

Ruth: I’m really embarrassed, ashamed not only of myself but of the whole of Kazakhstan, the second largest republic of the former you know what. Today in the UN General Assembly, among all the countries of the South Caucasus and Central Asia, only ours voted against the resolution on human rights in Crimea and Sevastopol. [8] What a shame! I do not understand: so many peoples, nationalities, nations, and states are under the heel of this terrorist empire, but Ukraine is left to fight alone! Why does no one, no one else declare war on the rashists? We say we support the Ukrainian Forces, but where are our own Forces?

Galya: Imagine what it would be like if the Kazakh Forces also entered the fight against our common enemy.

Ruth: Ha, I can imagine — we would open the Eastern Front and pull over half of the most mobilized! I mean, we have the longest land border.

Galya: All words are linked with forces and bring them to life: the orders of the commander-in-chief are also “just” words.

Ruth: I can imagine that — the Kazakh Forces, united with the Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Tajik, and Turkmen Forces, with the direct participation of the Georgian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Moldovan, and Belarusian Forces!

Galya: No criminal regime could stand that!

Ruth (speaks slowly in a singsong voice): In this case, I close my eyes and evoke the Forces of subject peoples, bound by the age-old seal of silencу… Now I see them — subjects and subalterns of the empire — republics and people’s republics, krais, territories and regions, cities of republican subordination and autonomous regions within krais and territories of various subordination, autonomous districts within territories and regions — all, as it was predicted in antiquity by the Soviet Constitution…

Galya: There are much, much more of us than it seems, us — Russian-speaking Russophone non-russians!

Ruth: I conjure Tatar, Udmurt, Karelian, Mordovian, Chuvash, Bashkir, and Crimean Forces!

Galya: I appeal to you, Aruakhs [9] of Sakha, Tuva, Komi, Adygea, Khanty, Mansi, Mari El, Chuvashia, Ingushetia, Ossetia, and Altai!

Ruth: I conjure the Buryat, Kalmyk, Karachay-Cherkess, Dagestani, and Kabardino-Balkarian Forces!

Galya and Ruth(together): We call for help from the sleeping languages — Karaim, Luoravetlan, Krymchak, Yukagir, Rutul, Alyutor, Baraba, Gogul, Itelmen, Kurmanji, Talysh, Uyghur, Avar, Tsakhur, Kryts, Budukh, Khinalug, Abazin, Evenki, Telengit, Tofa, Shor, Nenets, Dörbet, Khongodor, Tubalar, Sagai, Kurykan, Yunshiebu, Selkup, Kyzyl, Uzon, Ui-Beigo, Nganasan, Ashaabagat, Nivkh, Andagay, Chulym, Tsakhur, Shahdagh, Abaza, Mator, Koryak, Soyot, Ket, Ulch, Oroch, Ku-Kozhi, Taz, and Mugat!

Ruth: Let the dream pass, the time of sadness arrive, the time to throw off the rings and dresses at the bloody feast…

Galya: The time of war has come.

List of texts cited:

Galina Rymbu, Life in space (en)

Galina Rymbu, Poems for Food (ru)

Galina Rymbu: “The purpose of political poetry is to undermine the false supra-class mentality” (ru)

Galina Rymbu, Life in space (ru)

Galina Rymbu, Cosmic Prospect (ru)

La conciencia de la mestiza. On the way to a new self-awareness (ru)

Galina Rymbu, Insulting the authorities (ru)

Galina Rymbu, The dream is over, Lesbia (en)

Notes:

[1] The UN emphasises that these are only the documented cases, and the real number is bigger because many cases on the temporarily occupied territories cannot be documented

[2] Episode 1. Director Renzo Martens. 2003, 40 min. More about the film

[3] Julio Cortazar. Historias de cronopios y de famas

[4] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. by Betsy Wing. Available at link

[5] Ruth is talking about quantum entanglement, which has several name variations in Russian language, including non-locality

[6] For example, Rosi Braidotti on ‘nomadic feminism’.

[7] ZSU or AFU — Ukrainian Armed Forces

[8] More information about the resolution at the link.

[9] Aruakhs means ‘Ancestor Spirits’

***

Galina Rymbu is a poet, literary critic, feminist, anarchist. She was born in 1990 in Siberia (Omsk). Since 2018 lives in Ukraine (Lviv). Teaches philosophy of literature, gender literary theory, as well as original courses on contemporary ecopoetics and experimental and feminist writing in independent educational institutions. Founder and editor of “F Letter” — an online journal dedicated to feminist literature and theory, and (micro)media about contemporary art “Greza”.

Ruthia Jenrbekova was born in Almaty at the time of socialism. Participates in various enlightening and darkening projects since the start of the century. Considers herself an artist of a postmedial kind. Writes texts, gives lectures, studies, and appears before the public as a performance artist. She is one of the employees of Kreolex center. Lives and works in Vienna and Almaty.

The publication is made with the support of The Magic Closet and the Dream Machine: Post-Soviet Queerness, Archiving, and the Art of Resistance.