Future Presence: Documentation and Archival Material from the Exhibition

Editor’s note: syg.ma is launching a new section focused on spaces. It will highlight the current projects of our community of authors, self-organized initiatives, and institutions. In this series we will feature materials related to the history and theory of architecture, cultural geography, and visual research into landscapes and infrastructure. Regional scope will be one of the primary curatorial principles for this section — we want to limit ourselves to the so-called post-socialist countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Materials covering other parts of the world will only be included when this juxtaposition brings new nuances to the understanding of the aforementioned areas, highlighting their commonalities, distinct paths, and stories. This series was made possible thanks to the support of the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia.

As part of the inaugural material for this section, the curator Ana Chorgolashvili speaks about her background as an art historian, the renewed interest in later-period Soviet architecture, and a recent, three-part exhibition focused on the uncertain fate and potential futures of these structures.

Tbilisi Architecture Archive

Mariam Gegidze, Nino Chachkhiani, Natia Abasashvili

As an art historian, my research has been focused on post-Soviet architecture in Georgia, particularly in Tbilisi, where I was born at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Underlying my genuine interest in this architectural heritage and its social value, I have always wanted to better understand the legacies and evolutions of the material environments that have surrounded me through each phase of my life.

My fascination with this topic has been mirrored by a growing interest from the general, international public starting in the early 2000s, as publications and exhibitions centered on the subject have become more and more common. Notable titles, such as CCCP: Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed (2011) and the exhibition Soviet Modernism 1955–1991. Unknown Stories (2012) by Architekturzentrum Wien brought the subject to the forefront, as less academic mediums, such as instagram accounts and other forms of social media, illustrated the genuine enthusiasm that new generations and audiences held for these buildings.

For many, these concrete structures served as defining evidence of genuinely emphatic and humanizing projects. The revival of architectural movements such as Brutalism and the appeal of the socialist notions of equality have worked in combination, allowing for a renewed discovery of Soviet Post-War Modernist architecture. One might say that the growing interest in such architecture in post-soviet countries is motivated by the “sentimental” values that these buildings embody. However, due to the loss of many masterpieces from the Soviet period, it appears essential to “validate” those sentiments by providing not just an ideological argument for their preservation, but a coherent historical and architectural analysis.

The post-war political, economic, and systemic changes in the Soviet Union encouraged the abundant production of libraries, culture houses, sports complexes, and other, similar buildings that served public functions — all oriented around the concept of the common good. However, in Tbilisi as in many post-Soviet cities, a large number of public buildings from that period have remained without a function, are privately owned, and face destruction or brutal alterations. The system that gave birth to this architecture has collapsed. The new political, economic, and social systems of the modern day do not allow for the preservation of these large-scale, public good-oriented, heritage buildings, and so they are subsequently, successively destroyed. Nevertheless, these Brutalist buildings, often made of reinforced concrete, are still standing in Tbilisi’s city center and its suburbs, usually abandoned, radically altered to take on other functions and unsystematically absorbed by individual practices.

The condition of this heritage is complex, and the future is uncertain. How should this architecture be returned to the city? How can it respond to the challenges of modernity and remain at the service of the common good? If we deny our past identities, what are we creating instead? Do we have little control over the processes that form our living environment? To consider these questions is to realize the present condition with which we are presented: what kind of city we are living in and what might our collective future be?

Organizer: Czech Centres

Chief Curators: Henrieta Moravčíková (SK), Petr Vorlík (CZ)

Curators: Anna Cymmer (PL), Ábel Mészáros (HU)

The exhibition Future Presence addressed these questions and was aimed at underlining the social importance of the still-existing public buildings from this era. It was conceived as an opportunity to create a stronger feeling of identification towards the city and its recent past, to recall and actualize the memories of the broader society that have benefited from socially oriented processes.

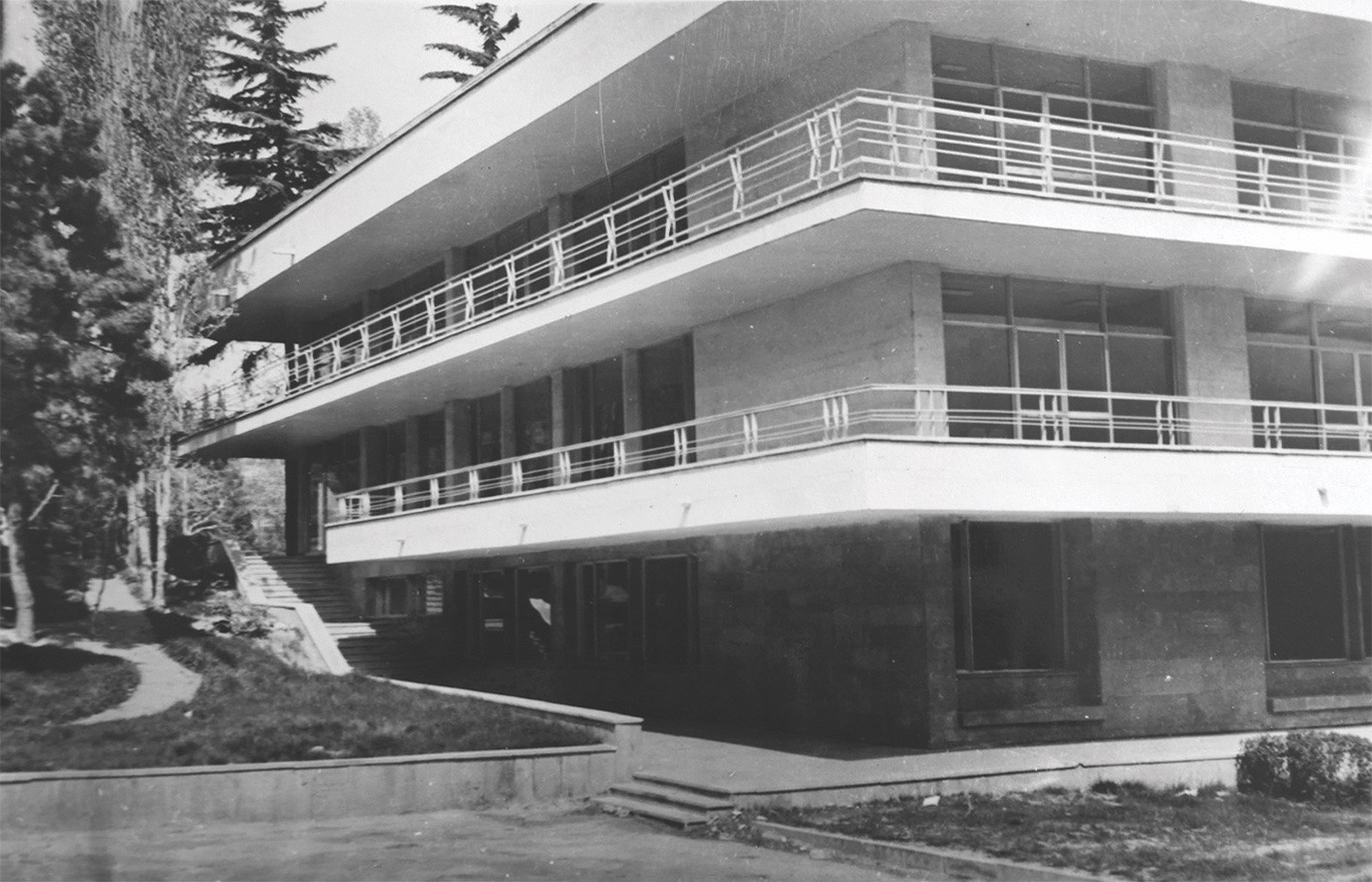

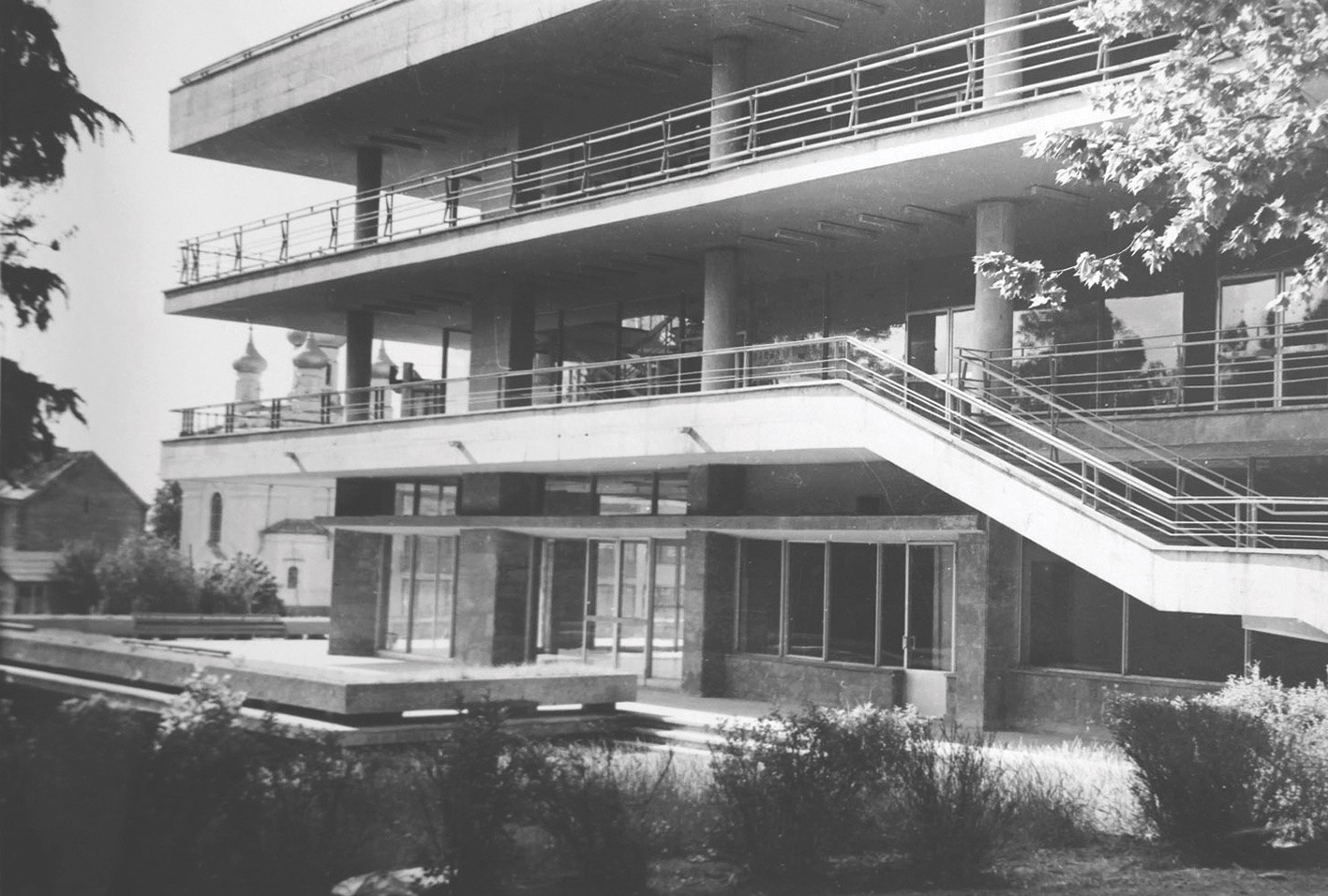

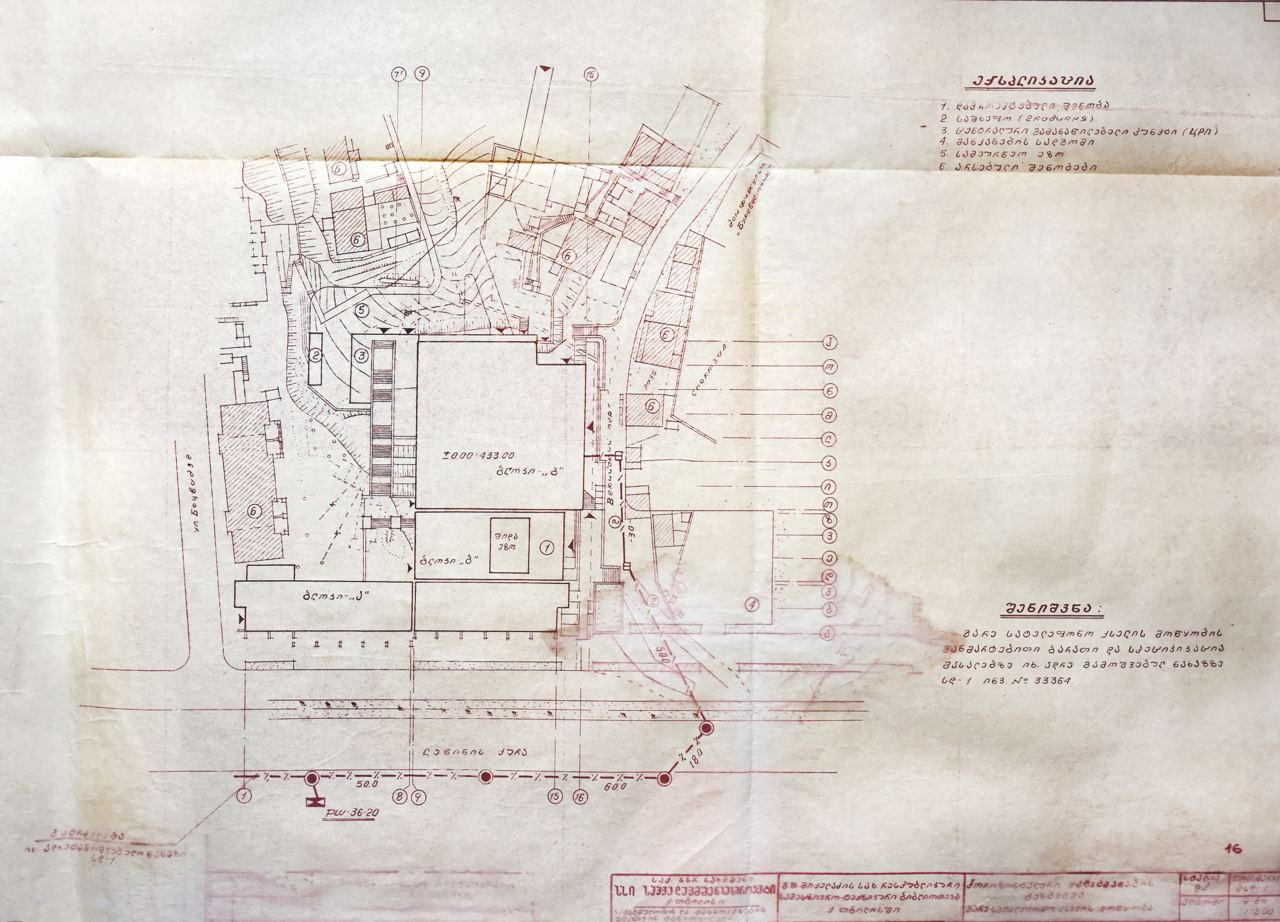

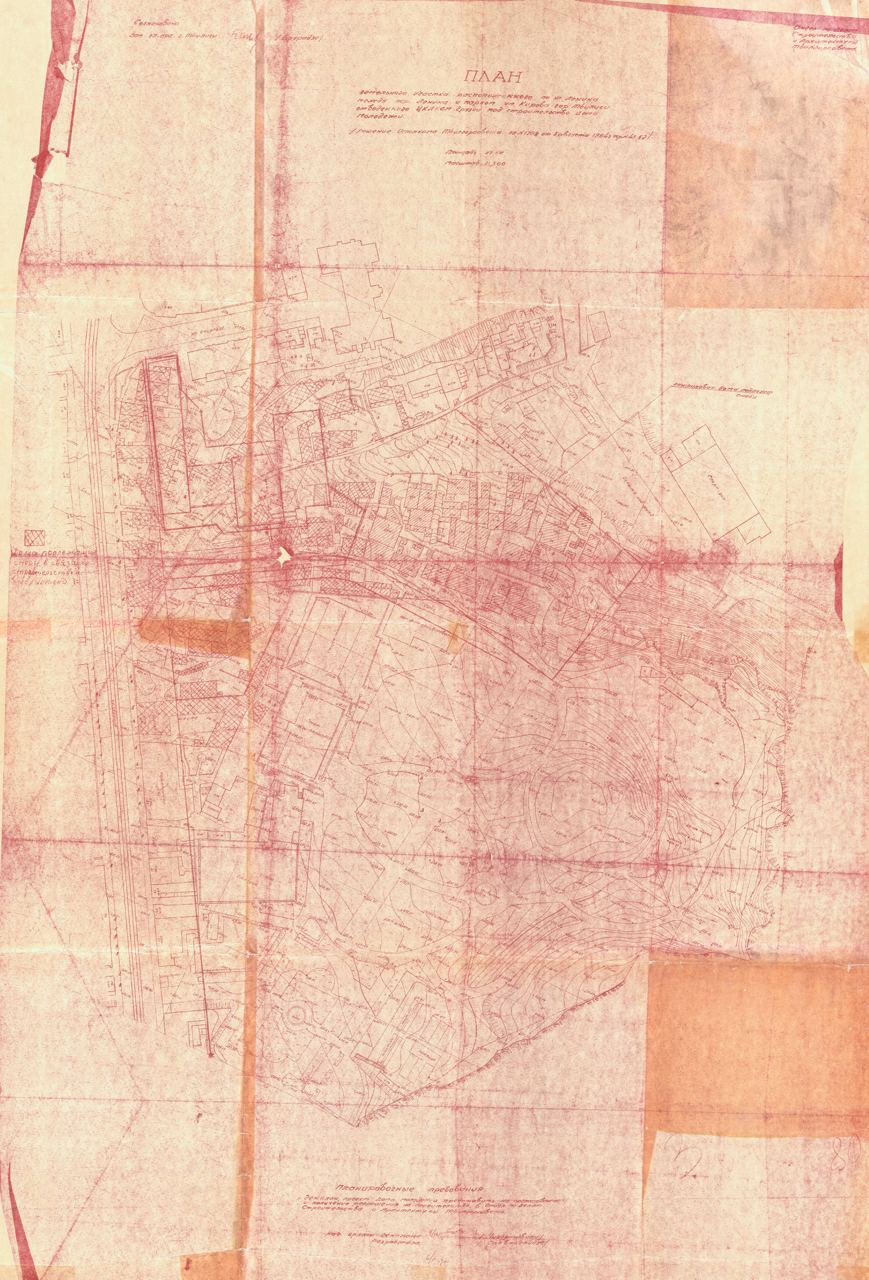

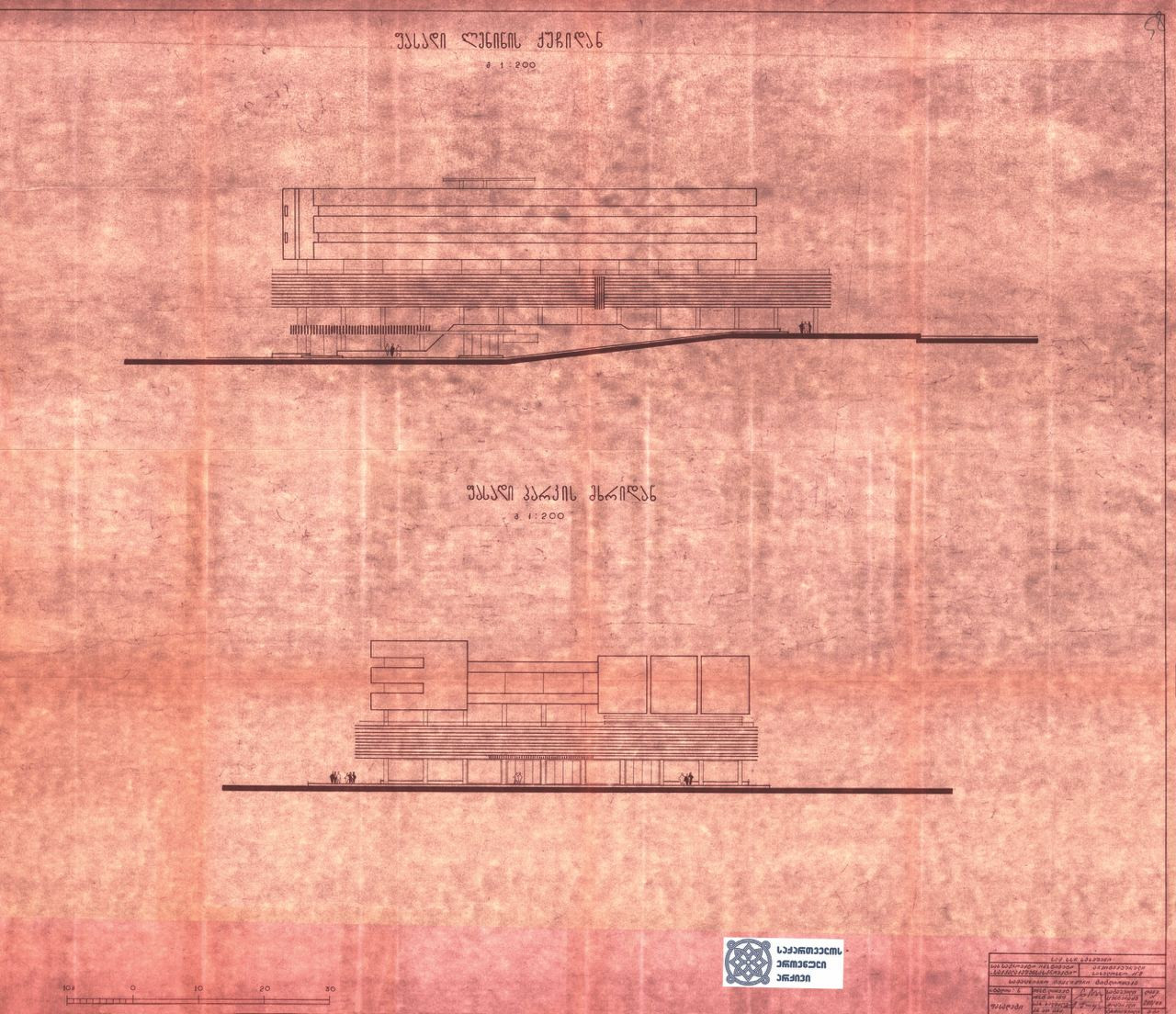

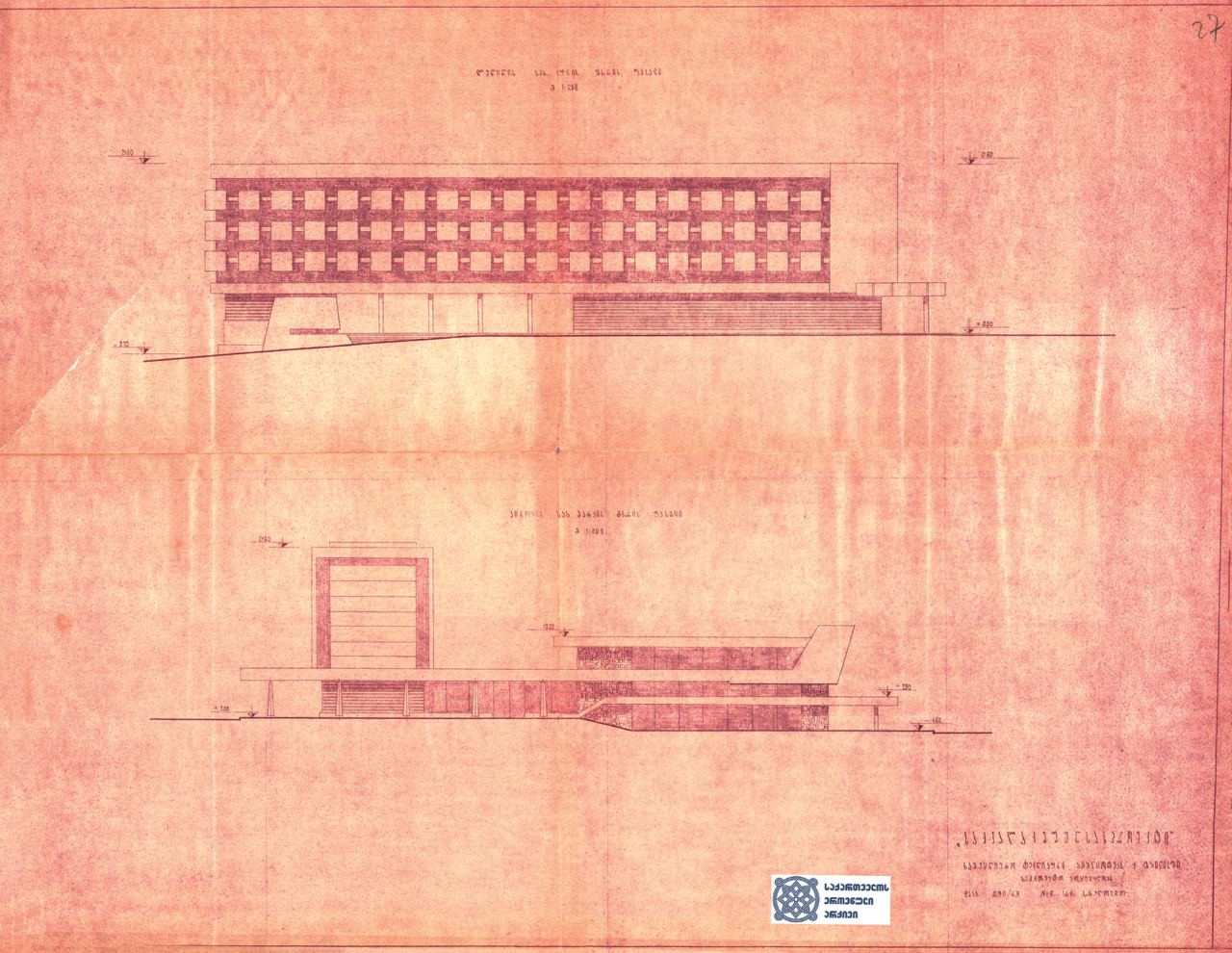

The exhibition combined three independent expositions. The show, presented by the Tbilisi Architecture Archive about the aquatic sports complex Laguna Vere, addressed an architectural perspective and highlighted the socio-cultural significance of this structure. The exhibition ICONIC RUINS? revealed the parallels in the architecture of the four Visegrad countries' shared state-Socialist past and initiated a broader discussion of the immediate future of the critically at-risk cultural heritage of late Modernism. Finally, the exhibition Future Presence presented the results of a workshop conducted with 2nd-year students from the Architecture program in the Visual Arts, Architecture, and Design School of the Free University of Tbilisi. The buildings in Tbilisi that were selected for research and observation are still operating (partly) as public buildings. Unfortunately, the Laguna Vere complex has been fully privatized and is on the verge of destruction.

All these independent expositions were linked through the study of post-war socialist architecture and served to deepen discourse on the future of this heritage. Here, on the one hand, there was the task of dividing the exhibition space into three independent parts and simultaneously combining it with repetitive design elements and creating a visual line following the conceptual narrative of the exhibition. On the other hand, the exhibition also hosted a public program with the participation of local and foreign experts. The program included discussions and presentations about the past and future of the post-war Socialist Architecture of Tbilisi and Visegrad countries.

![INDUSTRIAL-PEDAGOGICAL TECHNICUM, SCIENTIFIC-TECHNICAL LIBRARY, CHESS PALACE, AND ALPINE CLUB VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/_W2WXQqui3ma-0dz1U-QmrtmwJQr-8YddkhamZNc2P8/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzNjODU3MGIwOWQyNzg5YjhkZmYxOGY3ZWMzNGIzODdkYjczYjdmZjkvc3RvcmUvNGEzZWZiZTYzYTgxNjFkMDQ0ZTMzMTNjMzhlZDYzMjFiYWYzNzk0OGJiYzQ0ZWQ0MmJhYmRkMWMwZmY2L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

![INDUSTRIAL-PEDAGOGICAL TECHNICUM, SCIENTIFIC-TECHNICAL LIBRARY, CHESS PALACE, AND ALPINE CLUB VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/8AFtaaWs3zKHFnBdkgtYoab6B9x3qv5CZ6e1X29A7j4/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2UwNDc1YmJmZjZhZmZiNDViZTQ2MjE2NGMxMTZmZTgwYzNjNmZlNGQvc3RvcmUvODNkMTUxMTNmMTU2ZDMyODA3ZTJlNGUzZTE3NGJhNjYxYzQ0OWIyOGY5NTg5YmQ5OWM5YTkyMWEyNzQ1L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

![INDUSTRIAL-PEDAGOGICAL TECHNICUM, SCIENTIFIC-TECHNICAL LIBRARY, CHESS PALACE, AND ALPINE CLUB VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/DqiwZJ_VZhNuGKxTFex3rlFNOaqOYWeH-XPdrrkIgUc/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzU5YzQ0Yjg5NDBlNDc3NmVlZTQwYzE0ZWZiNmU5MTIwZjNlMDc3NTEvc3RvcmUvNjE3MmYwMThhMzU0YTk0YzNmZTEyNDU1MTE3M2I3YTg0NzA5ZTBmY2RkMzkwZWZjNmIwYTMxM2EzZjQ5L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

![INDUSTRIAL-PEDAGOGICAL TECHNICUM, SCIENTIFIC-TECHNICAL LIBRARY, CHESS PALACE, AND ALPINE CLUB VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/fbgK8JWY6_oYgKPpgG4Fsz44rKZ66t3fqWBe3YTsmbs/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzk2YTkzMGQ2ZTQwYTIyMTBjNWVmMzQ3YmM2OGQ2OTgyZDU2Y2Q0ZTAvc3RvcmUvNzdkZjYzYjgzZDczYThjYWI0MWQ1NWMyOGE3MmQ1NzE0ZGJhNWE1NjMyYTk2MDAzZTY4YmU0NTAyMWJiL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

![INDUSTRIAL-PEDAGOGICAL TECHNICUM, SCIENTIFIC-TECHNICAL LIBRARY, CHESS PALACE, AND ALPINE CLUB VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/bXRIX65BbCN3rHwIaMV3e-UETVWeGBpgOq6rKcjWDjg/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2Q3ZDhjNzA0YjBjYjcxN2Q0NzlkYjgyODc1M2YyNDQ5OTgzNTZiYzAvc3RvcmUvN2MxZDU3Zjk0ZjU2YzY0NTVmZWRiNzY1MzVmMjdiOTRjZDlmNGJkNjhmYjIwMjVhYmMxYjBjMjVjNWJlL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

![INDUSTRIAL-PEDAGOGICAL TECHNICUM, SCIENTIFIC-TECHNICAL LIBRARY, CHESS PALACE, AND ALPINE CLUB VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/WdSXBTBtd3BiIMsYQQ2FkOtjFoEKSmFYglkbjiK-_Kw/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzk4ODlmYTY4YzIwODJiMGE0NjRhZDNiOWJhZjRhZjQ4ZTFjYTdmYWQvc3RvcmUvNjAzNDZlZTEwZjNkMDgwMTY2ZTJlOWRiMTk2MWM3ZTE5N2RiZWIyZjgyNDBiOGJiYmYyOGNmMTU1YThiL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi

As mentioned above, the recent increase in interest and affection for Soviet architecture is evidenced by a number of exhibitions and publications. On the scale of the local Georgian context, there have been multiple publications and exhibitions dedicated to Georgian Soviet Architecture. These include the exhibitions Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili, Architect on The Edge of Epochs, 2022, Hotel Iveria, The City, and The Tower, 2022, Dynastien, 2018, Georgian Modernist Architecture 1955 — 1990, 2014 and the publications Building Socialist Georgia, 2022, Art for Architecture Georgia: Soviet Modernist Mosaics from 1960 to 1990, 2019, Soviet Bus Stops In Georgia, 2018, among others. This activity, along with the international attention given to Soviet architectural heritage in general, gives us hope that the irreversible process of destruction will slow down in the future, and the tendency to forget will be replaced by a tendency to observe.

Curator: Ana Chorgolashvili (GE)

Design of the exhibition: David Brodsky (GE); Assistant: Nikoloz Tsagareishvili (GE)

VA[A]DS: Visual Art, Architecture & Design School. Free University of Tbilisi (GE)

Tbilisi Architecture Archive (GE)

Iconic Ruins?

Chief Curators: Henrieta Moravčíková (SK), Petr Vorlík (CZ); Curators: Anna Cymmer (PL), Ábel Mészáros (HU)

Public Program: David Bostanashvili (Georgia) Lado Vardosanidze (Georgia), Tamar Khoshtaria (Georgia), Nikoloz Lekveishvili (Georgia), Peter Szalay (Slovenia), Petr Vorlík (Czech Republic), Dániel Kovacs (Hungary), Ania Cymer (Poland), Michal Murawski (Poland)

The project is sponsored by Visegrad Fund and Co-funded by the Creative Europe program of the European Union. The project is realized in the frames of the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial, 2022.

Additional Materials

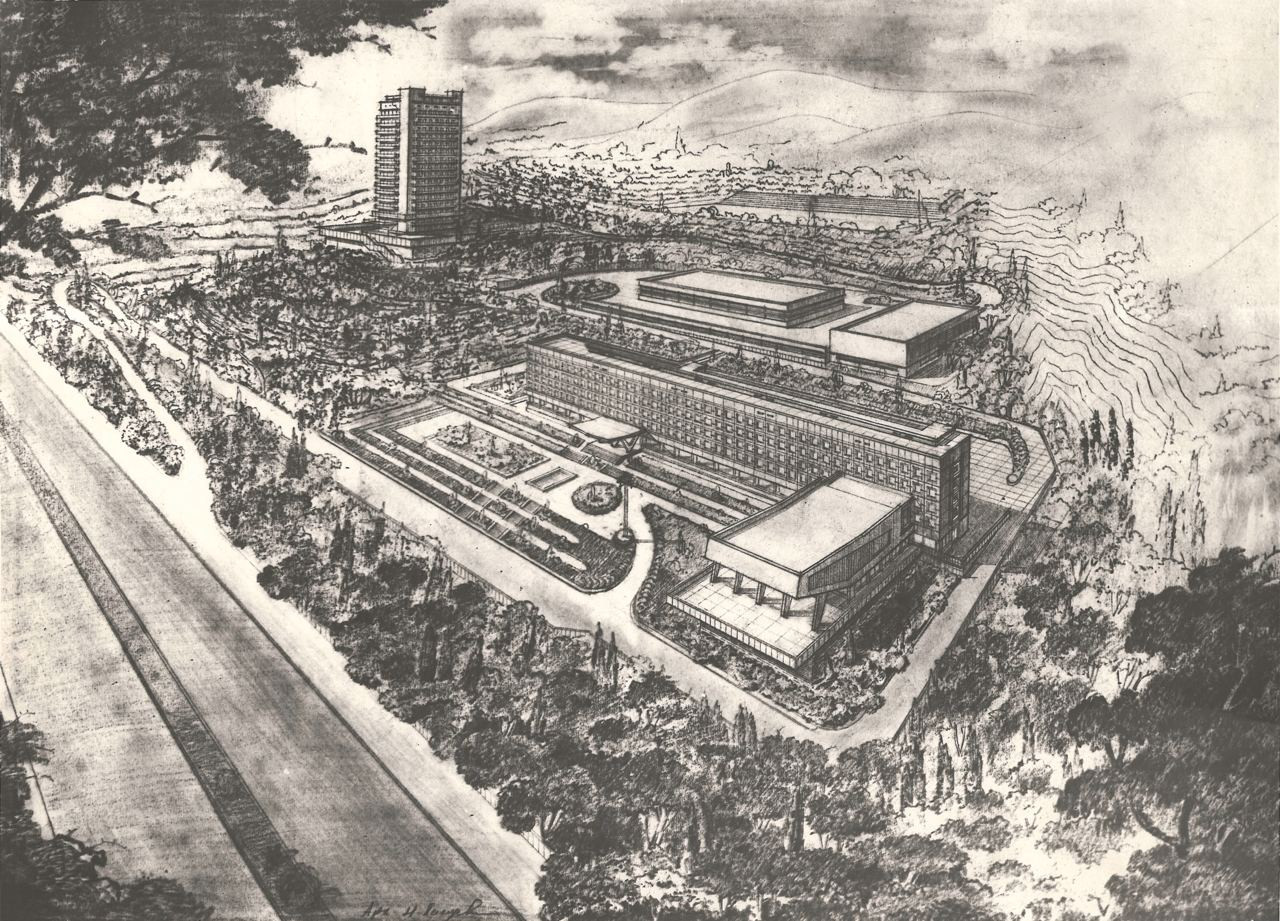

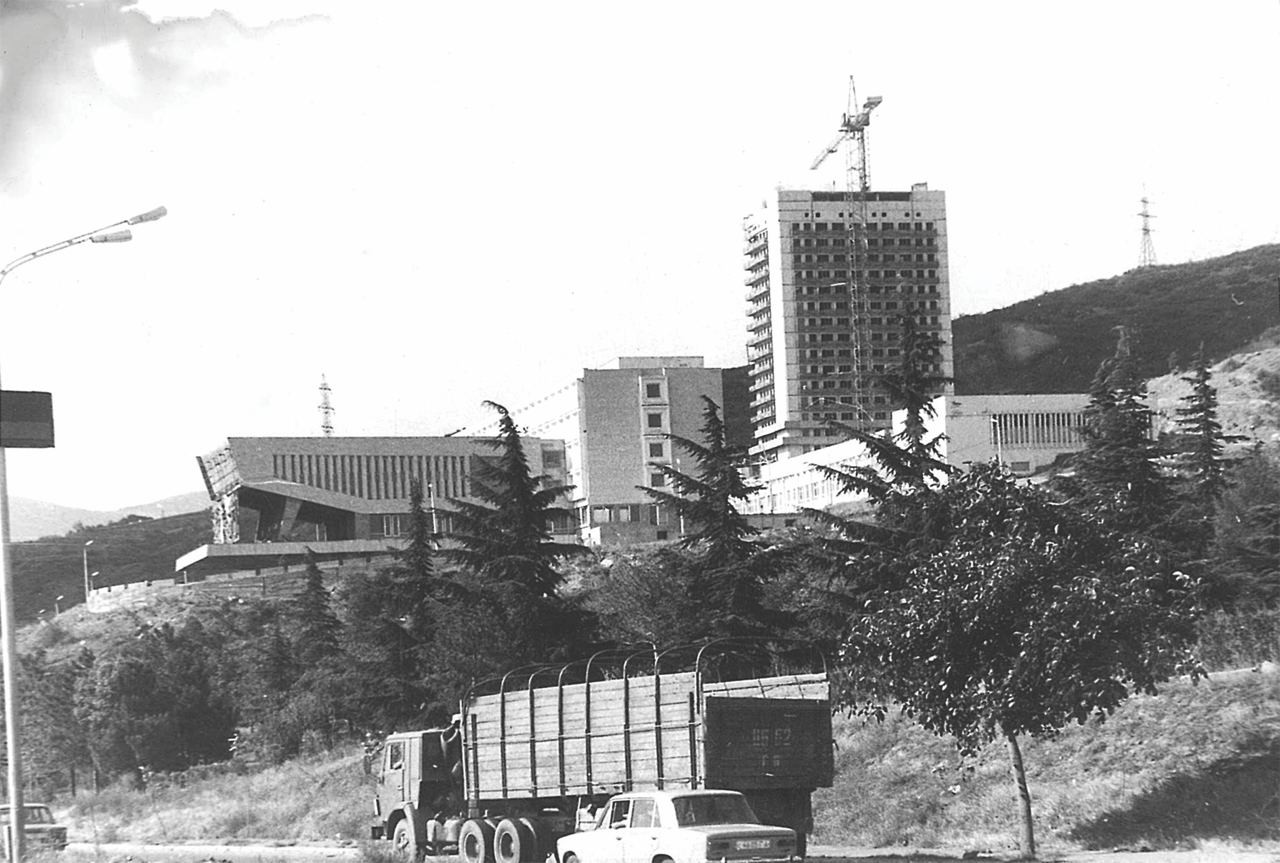

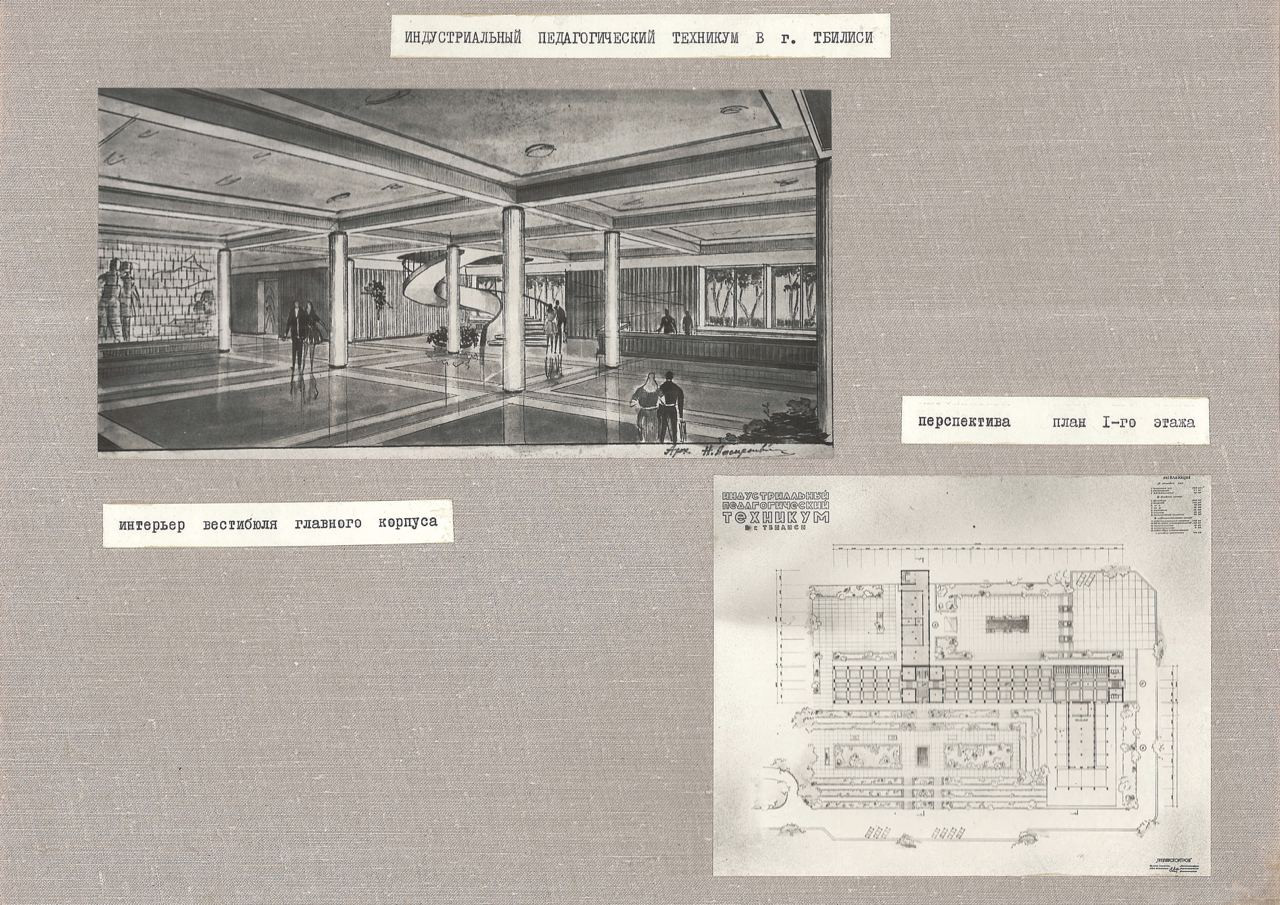

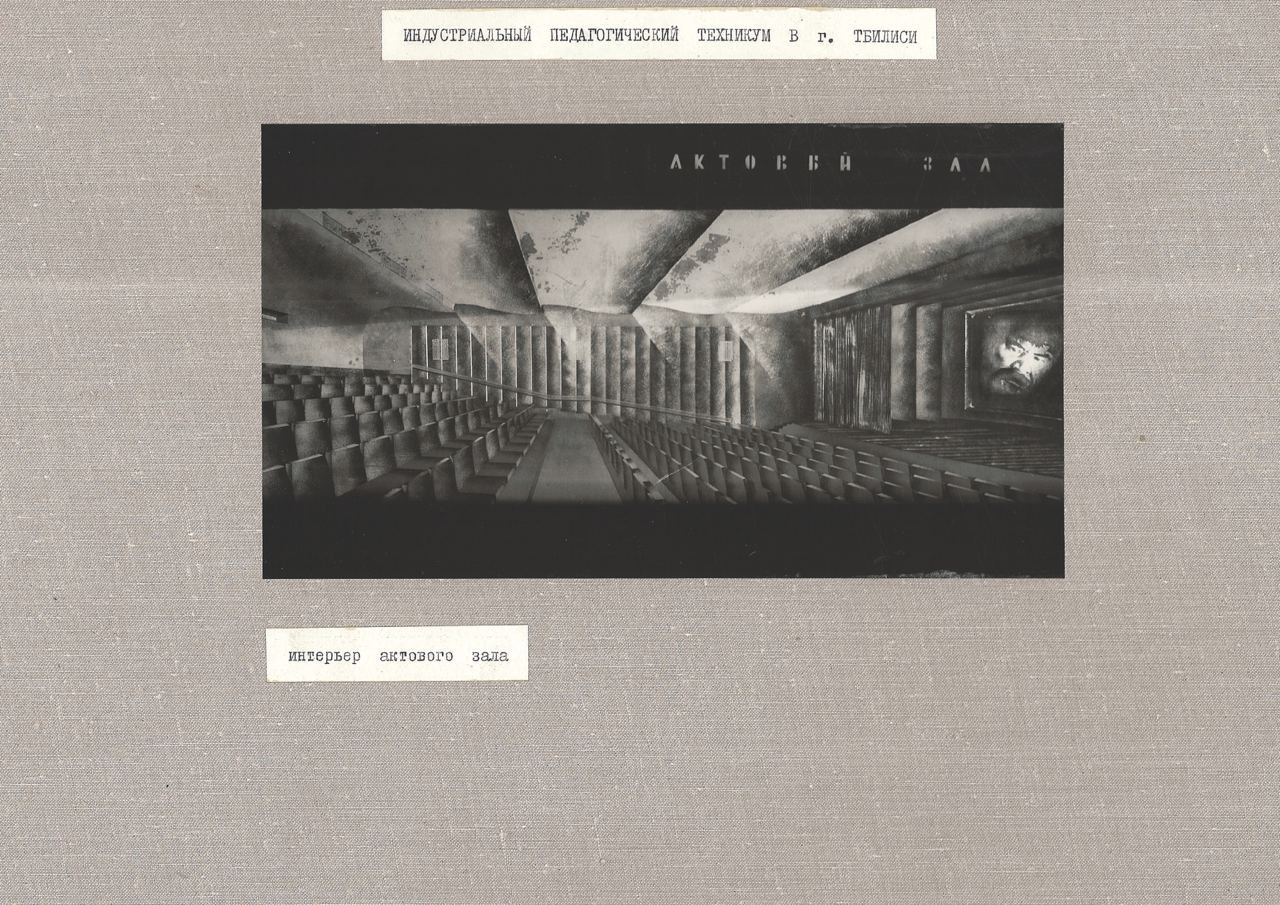

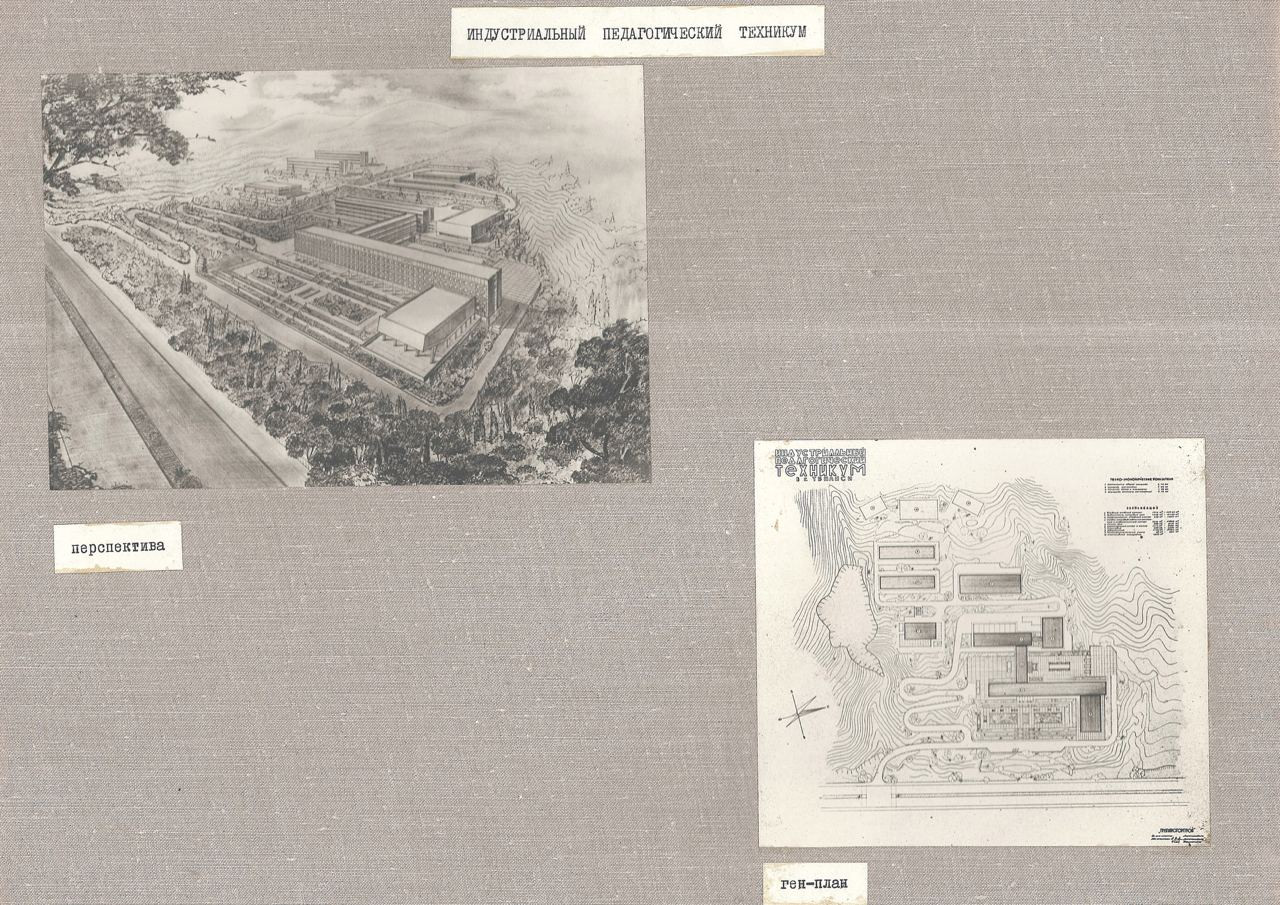

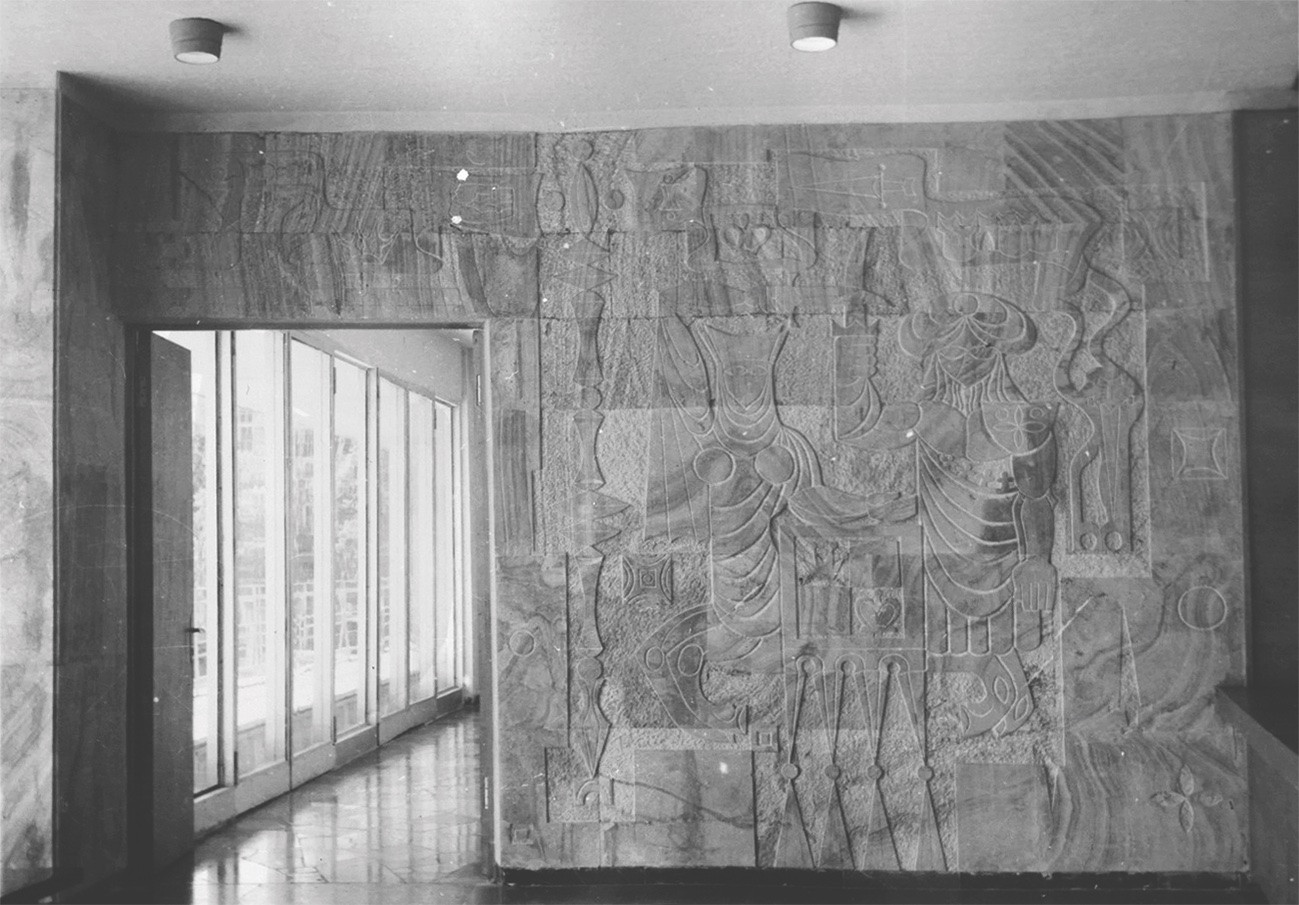

Technicum

Architect: Nikoloz Lasareishvili, 1978

Drawings, sketches, photos from Lasha Mindiashvili’s family archive

Tutor: Architect Thomas Ibrahim

Chess Palace

Architects: Vladimer Aleksi-Meskhisvhili and Germane Ghudushauri, 1973

Photos from Germane Ghudushauri’s personal archive

Tutor: Architect Lasha Shartava

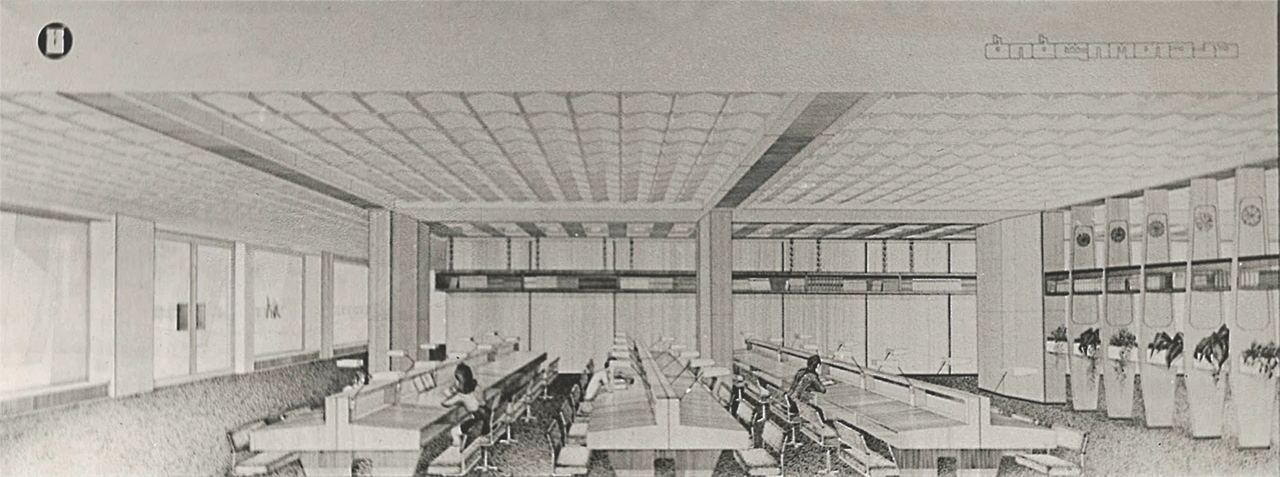

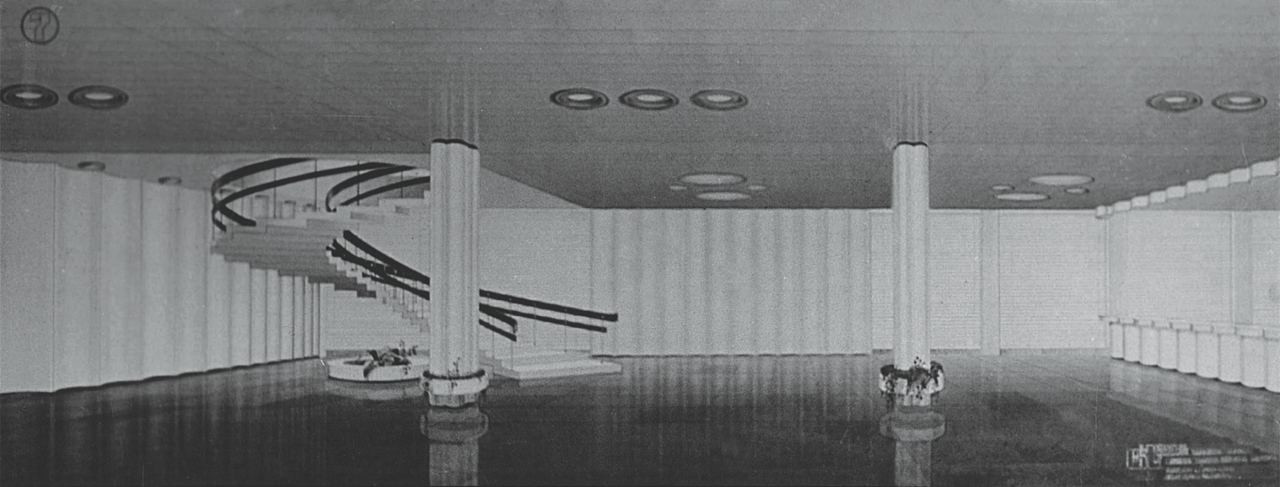

Technical Library

Architect: Gari Bichiashvili, 1986

Drawing and plans from the National Scientific Library of Georgia

Photos from Gari Bichiashvili’s private archive

Tutors: Architect Nano Zazanashvili and Political scientist Erekle Chinchiladze