Standard time: a conversation with the filmmaker Cyril Schäublin.

From Issue 4—General Public — Summer 2020 (Archive)

****Spoiler alert! ***

We recommend viewing the film hereon Vimeo pay per view, before reading the interview. The funds go directly to the filmmaker.

Nacre: I wanted to speak to you after watching your film “Those who are fine, ” which I thought was really apt and humorous. In particular, because of the Swiss perspective it offered: a look into the legacy of minimalism and Swiss aesthetics. I felt like I haven’t seen this angle before: the way the film worked through that Swiss formal legacy, and how the formal approach intertwined with the contemporary questions on wealth, digitalization, the internet and, with subtly militarized everyday. To start, as an introduction to the readers, I wanted to ask you to describe what you do in your own words, and the context.

Cyril: Right, yeah, so… I grew up in Zurich. It’s funny because just yesterday we went for a walk with my old friend in the neighborhood where we both grew up. We talked a lot about the early formative period, from ages two to six, and the relationship one establishes to the architectural spaces during that time. I think a lot, particularly as I am preparing for my next film, about how the world begins to be constructed, from our early childhood, onwards. There is a German word I am thinking of that I can’t quite find a good translation for it in English — behauptung. I just realized, walking through that neighborhood, what a strong impression this neighborhood had on me.

So, I grew up in Zurich, and then I went to Argentina when I was 15, for a student exchange. That already shifted my relationship to space. Then, after I graduated from highschool, I went to China for two years and this was a very important period for me. Because — I don’t know if you have been to Zurich — it’s very different from Beijing or Berlin (where I also lived for 8 years). Zurich is so made, it has never been flattened, or destroyed, or rebuilt. So that’s my biographical context.

In terms of what I make, I work in film, or in cinema, but I think the currently existing distinction between art and cinema is also very interesting to me. Because cinema is such a young art form, there is still so much to explore or to make out of it. And sometimes I feel like this separation of film and art today, is what then becomes a cinematic formula. Most of the films we see, it’s almost like there is a mass psychosis, or an unspoken agreement that cinema is “supposed to be done like this.” 99% of films we see are done in a set way. I don’t want to just be negative and declare that I am doing something so much more different, or better, but I am very aware of these unspoken rules that define what films should look like, how the films should be narrated.

N: What do you think dictates these normative or formulaic parameters? Where does it come from, or what is it for?C: I think that humans are just like that, we tend to normativise, or settle into a pattern. Of course cinema has changed, and has been reinvented many times over the course of its history, but the status quo always catches up to us and becomes a kind of distillation of an approach into a comfort zone. I am really interested in the idea of trying to step out of these zones of comfort, or zones of unspoken agreement. And I am invested in re-looking at these systems. Going to China at 20, it really made it possible for me to shift out of my normative context, and to be able to look back at it, as if having an outside perspective.

N: What are your thoughts on propaganda, and how it works. Does it exist, I mean besides the obvious authoritarian forms in places deemed as undemocratic?

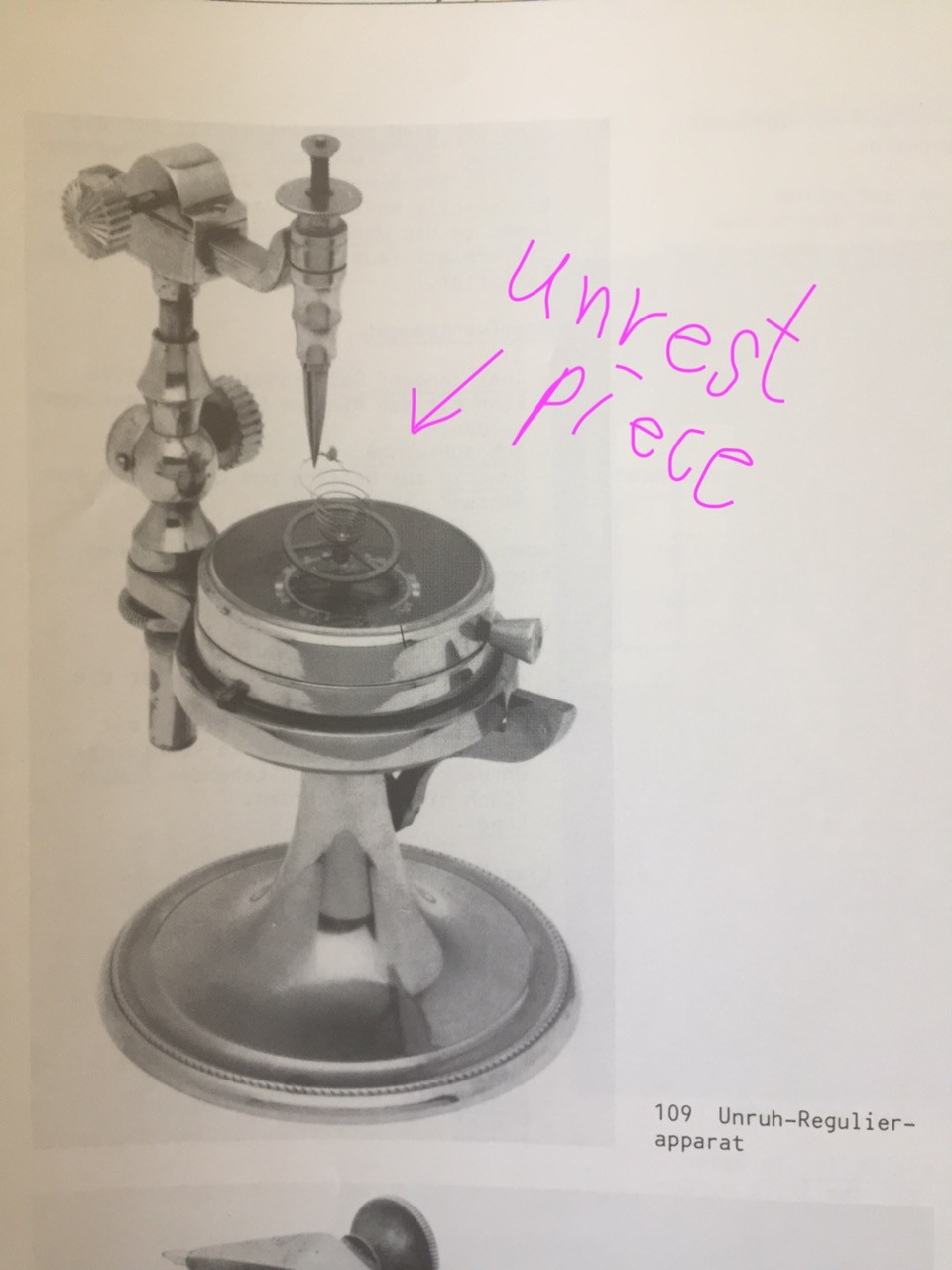

C: I think it’s hugely important. The question–what is propaganda. Maybe this is a good moment to talk about the new project. It takes place in Switzerland in 1877, and I would say, during a period when a lot of the things we have now, or certain agreements, as we can call it, have been invented. Like a lot of technology, telegraph, photography, time sync, the mechanical clock.

The film will be essentially about the anarchist movement, which started in Switzerland between Russian and the Swiss at that time. Saint-Imier valley became important for the growing anarchist movement in Europe, in Fédération Jurassienne (Jura Federation), because Switzerland was libertarian and there was free press, so, for example, Spanish anarchists came to Switzerland to print, or to pick-up and transport out the printed matter back to Spain, or to France, and even to England. What is interesting about that time though, in showing how propaganda worked, is what happened in Switzerland. This was the time of the formation of a national cult, or nationality, national state, that happened everywhere in Europe around that time. The medieval battles were celebrated again, and the construction of a national “we”, as a country, happened. And that’s what the film is trying to show: how this anarchist project of making an alternative reality used the same tools as the normative national project did, mirroring practices of publicity and platform creation to tell their story, their version of what was happening. And there is quite a bit of similarity of that period to the present moment: there was a financial crisis, in 1873. And… I don’t know, do you know about Kropotkin?

N: I was just going to ask you about him! Given the subject of the 19th century Swiss/Russian anarchism. I just learned about him via Lynn Marguilis. Do you know her work?

C: No, I don’t know her.

N: She is an American evolutionary scientist focused on symbiosis in biology. And, well… I need to research him and all of this further, but she has started her work, on cooperation across species, by expanding on Kropotkin’s book “Mutual Aid”. And so he was this key figure, of the anarchist movement, who lived in exile in Switzerland…

C: …exactly, and in his diaries, or memoires, he talks a lot about economic despotism. I think that’s so important to understand, going back to that time. It’s so obvious, to me at least, that this nationalist and libertarian projects — and all these national cults, new rituals, like the invention of national hymn, etc. — you can see it was all such a distraction from what was actually happening, which was this economical despotism. Like, for example, at the village where the anarchists congregated where the watch factories were, the factory owner was in the Swiss national movement, but in fact, his main revenue came from the international business. Switzerland, to this day, remains the center of watchmaking, and there is a very specific history tied to that. At the time, at the end of the 19th century, there were three hundred people employed in Switzerland making watches, and these watches were imported everywhere in the world. That was the point at which the watch manufacturers invented this language of competition, “La concurrence du déhors” in French, or “We have to fight back!” They began saying that, it’s a fight, you know, on seeing that Americans and other producers were starting to enter the watchmaking market. And the anarchist movement, on the other hand, was really after building an international movement of cooperation. In a capitalist way. Like Kropotkin, they were pro-capitalist, but their idea was, we have to be in control of our own production and just cooperate internationally on distributing the market wisely, not have these competition between the different countries.

N: But Kropotkin, I thought, was slightly different, because he wasn’t for capitalism, as far as I understood it, in that his project was really about independence and cooperation, or mutual aid, and he saw private ownership, privatisation of resources, as the main issue of dominance. And he was disappointed by the Bolshevik interpretation of the socialist project, when he went back to Russia at the end of his life.

C: I think here it’s down to the different use of the vocabulary now, and at that time, in the precapitalist epoch as we know it. They used the word “capitalist” for someone who produces and is in charge of their own resources, independently. And the project of anarchism was a project of linked cooperative distribution of capital, as opposed to a competition. And it’s really interesting to go back to that time and to think of why they lost, this essentially, battle of two different narratives. Why did their narrative fail? From the point of view of today, their project makes so much more sense!

N: That’s still similar to how we think of capitalism today, whether it is or isn’t related to competition… Meaning the project of true non-ownership, cooperation and sharing is distinct from merely being an independent producer, in that you don’t have control over the resources. Lynn Marguiles whom I mentioned earlier, she placed the invention of the mechanical clock as the pivotal moment in history, when human excellence became so convincing, and it’s product, the watch, so intimate, it’s on your wrist, it’s in your home, that the progress became equated with it, and the narrative of STEM became absolute, thus proceeding, unquestioned, for centuries to follow.

C: The question of time, it is really interesting: that we are so used to it, it has become so real, so concrete, that it would be hard to imagine it ever have been otherwise. This theme will be important to the film. The project of standardizing time was very difficult, in particular in the US, where they had a lot of problems, like train accidents, because different cities, in different time zones, didn’t have their time schedules synced. The way it was done in Zurich, and in Paris, is by sending the time signals with a telegraph, and smaller cities had to adjust the local clocks to the centralized reference point. So for the19th century, the synchronization, it was this huge undertaking. What’s funny about the village where we are setting the film, there were 4 versions of time, the factory time, the church time, the official local time, and the national time. So this really is a stark reminder of what, like you said, the central place the watch occupies in our lives and in history. But it also reveals the construction that is behind it, again this behauptung. The sync was a kind of power struggle for dominance too: who will, in the end, dictate the measure by which we all live.

N: Regarding time, the making of your film has been postponed until next year due to COVID-19 situation, right?

C: Yes. We had to postpone.

N: You are working with a team, or…

C: Yes, that’s the thing. My last film was made by a small group of people, myself, the DoP Silvan Hilllman and some help from friends and family, sort of. Which is the way I’d like to continue working. But in this case, because it’s a historical film, but also not quite a historical film, it’s different. What I find I am more and more interested in, is what may on its surface seem like a random language, which doesn’t seem important or worth showing. In the last film it was passwords, or talking about health insurance and internet providers, it’s something that’s supposed to be bullshit, uninteresting. But these things are happening, it’s a kind of code, or through thread of language, and a big part of our existence. So the idea is to apply the same method to the past, like, we don’t want to show all of these red flag demonstrations, or clashes with the police, or the kind of images that we have already seen, and that supposed to imply what the revolutionary movement looks like. Instead, I want to go for situations, where people are in the process of handling something very simple, like organizing a watch factory at the time, and structuring salaries, and that kind of mundane stuff. So the film will be more difficult to do then the last one, because we need costumes, we need a watch factory, we need people to help out to make this happen. So we have a lot more people involved. This is the reason why under current circumstances of COVID-19, it becomes impossible to make the film this year. If I were making something like my last film we could still pull it off, but not in the case of a bigger production. And I do gravitate normally towards an easier, low-budget production… But I also like the idea of making a kind of period film.

N: So if you naturally gravitate to a more intimate way of working, how did you come to making the current project?

C: This idea is actually much older then my last film, so it has to do with the fact that I spent so much of my life outside of Switzerland. When I was still in the film school in Berlin, I asked myself what kind of film could be made, if the story was based where I am from in Switzerland? I come from a family of watchmakers, like working class factory workers, all of my father’s family line, aunts and uncles. So I have seen the inside of the watch factory when I was a kid and spent some time there. Then, through my brother who studied social anthropology at Oxford, I came across a lot of the 19 century anarchist texts. So things just kind of came together, the more I read about it, the more it felt important to make something about it. And then I came across a PHD thesis of this relatively young historian, Florian Eitel, who has published his doctoral thesis about this watchmaking valley and the anarchist movement there.

N: …And, while you were gathering research for this coming film, in the meantime you made “Those who are fine”? I wanted to ask you to speak about its title and about how the film came about.

C: Yes, so, the title comes from a song, and it came at the end of making the film. I wanted to make sure to choose a Swiss German title, just to be more situated in the specifics of the locale. I thought the title of the song is not as much about spelling, or dialect, so it would work well… And this musician [editor: whose song’s lyrics were used as a title] is someone who is very popular in Switzerland, he is known and loved by everyone, which is sort of unique. So children know his songs, the older generation, people on the left, or right, everyone. And for the Swiss the connection to the song has a very strong associative reaction. The song basically speaks of the problem of wealth, as a benchmark, and how difficult it is to give up that benchmark. It’s almost Wittgenstein in a way, hard to explain… It goes a bit like this:

THOSE WHO ARE FINE (or better translated “WELL-OFF”), WOULD BE DOING BETTER, IF THOSE WHO ARE LESS WELL-OFF, WOULD BE DOING BETTER; WHICH IS NOT POSSIBLE, WITHOUT THOSE WHO ARE DOING BETTER; WOULD HAVE LESS, SO GIVE SOMETHING, TO THOSE WHO ARE A BIT LESS WELL-OFF, BUT WHICH IS NOT POSSIBLE, WITHOUT THOSE WHO ARE BETTER-OFF, ARE LESS-WELL OFF, SO THOSE WHO ARE WELL-OFF, WOULD BE DOING BETTER, IF THOSE WHO ARE LESS-WELL-OFF, WOULD BE DOING BETTER, WHICH…

And so on and so on

The film also had to do with me going back to Switzerland after a long time away, moving back, and listening to people, observing things… And then I came across these fraud stories. The fraud, the storyline, it was a sort of alibi, a through thread to talk about a collection of other places and issues that I had been thinking about.

N: Right, the old folks home, the atomized society, the slow burn of depression, kind of continuing the topic of bourgeois ennui started during the New Wave. But unlike in your film, in real life these types of crimes, this friend-of-your-niece-in-trouble phone scams on old people, they remain unsolved, because they are very hard to track since cash is exchanged. In your film, though, you do solve it, the fraudster is arrested. What was the impulse for this, we could say, happy ending?

C: That’s a good question. I don’t know! I must say that I like to work with a film, in a way… by giving it a sort of loose frame, but then I like to invite what comes, another logic, which isn’t always coming from me, or is controlled by me, it unfolds during the making. The static frames are what I started with, the kind of formal direction, but I allow things to happen during the filming of it. I don’t want to begin by saying that I know exactly what the film is. It’s clear to me that I don’t know a lot of things.

N: So there isn’t a script?

C: Yes there is a script, or scripted scenes, but I was more interested in specific choreography, like bank scenes at the counter, and I knew those definitely had to be in the film, but the arresting scene was almost insignificant, like it was just one of the other transactions that happened. Neue Zürcher Zeitung said about that arresting scene, that it is “the most unexciting arrest” in the history of cinema.

N: It literally is!

C: Yes, I wanted it to be a repetition of a code, numbers. I think I wanted the arresting scene in the film to show that all the elements, meaning people, are interchangeable in this scenario. A Chinese client that goes to a Swiss bank, policemen, bank employees, they can all exchange the roles. It’s the system that creates the impulse, it’s an exchange of these codes that defines their actions. So an arrest could be a kind of catalyst, or a catharsis, but instead all we see is another kind of, almost irrelevant, or unremarkable, transaction. I think the best feedback about the fraud storyline that I have heard, was from this ninety year old man who said he knew why these older people would go along with, or buy into, these scams. He said that they may have been aware that it was happening, that they were being taken advantage of. And that fifty thousand swiss franc was a price worth paying for a connection, or for a few hours of intimacy or relationship outside their very lonely, or institutionalized, lives.

N: I think I understand what he meant, in a way the level of comfort and medical care of their retirement setting, is an aspiration for people in other countries. It’s all so perfect and comfortable, but also entirely alienating.

I’d like to stay with the ending for a little longer, and zoom in on the description of a decision that you do ultimately make for the film, the arrest of the criminal, as a thing that is “not coming from you”. What do you mean by that?

C: It leads to a James Bennign class that I was fortunate to take back at school, called Looking and Listening. During that class, you just go to a place, without a camera or anything else, and you are training yourself to look and listen to a place for a few hours. I think it’s really important to do this. It may sound esoteric, but I do think places have their own logic, and voices. There is so much to get from just observing a space for a while, seeing how people use it. What concerns me about this process, that we have discussed at the beginning, this mass psychosis that I see in cinema, of sameness, is also reflected in the look of the film set. In the city, when you come across them, the filmsets have a feeling of a police cordon, or police presence, all these walkie-talkies, vests, road blocks, separation. Another influence for me, is Lav Diaz, whom I was fortunate to have met. His films are extreme examples of this anti-filmset kind of separation. He just goes someplace with his friends, who are also acting in it, and something happens which becomes a film. I also like working with my brother, who is an anthropologist. The anthropological project, it’s about examining a certain space or a scene, and it’s not about interference or judgement, it’s about trying to understand what is happening on the inside of where you are.

N: We live in a culture that has largely abandoned most of its sensory receptors, relying very heavily on ocular perspective. And production of images is so omnipresent, it can feel evacuated, and hard to continue contributing to the pile at this point. How do you work through that?

C: I think, it’s about what we put at the center of our lives now, and it’s an incredible moment to live through, when it is the photography, and moving images, that are at the center of the world. The production of the images is what’s at its center today. Italo Calvino, at the end of Invisible Cities, ends with “The hell of the living is not something that will be. If there is one, it is what is already here, the hell we live in every day, that we make by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the hell, and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of hell, are not hell, then make them endure, give them space.” So talking about these things like Instagram, it’s much easier to just accept it, fall into that flow, and more difficult to distinguish what is not hell inside the hell, and point it out, say this is something else, or give it space and endurance. For a long time I didn’t believe in the word politics, I mean what is it? Epistemologically it comes from Greek for city, citizen, so it just means organizing togetherness. But what do we talk about right now, when we mean politics?

N: Yeah, Garry Shteyngart 2010 book “Super Sad True Love Story” was so strangely prescient about Instagram, about so many things in fact, perhaps even the Trump presidency (given it was written around 2008, published in 2010)… In the book there’s this fine print that runs through all the communication between the characters: “switch to images”… There are compelling reasons why images supersede written language in globalized media, because the translation is not regimented by a linguistic fluency, or access to one specific culture. But it’s also not the first time in our history when we use images in this way… Even if we think as far as Egyptian hieroglyphs…

C: Around 1860-1870, in Europe, it became affordable for the masses to have a photo autoportraits made of oneself, in France called carte de visite, and this became very popular very quickly. In the first year alone, the photo portrait of the English crown prince sold forty thousand copies in England. People traded images of themselves, or they collected portraits of known figures. Like if you were a socialist or anarchist, they would trade images of Giovanni Passanante, and the like… So yeah, of course this is nothing new in a way. But still, in relation to what particular images we make now, what we put at the center… If you think about the standardization, it’s a very big question. Instagram makes me think of the architecture of Swiss banks, I don’t know how to say this, but it’s this aesthetic that’s so… It’s so sure of itself, so concrete, so locked, and it’s so extreme in its expression! I think it’s very exciting to see where we go from here.

N: In terms of anthropology of the present, and in general — anthropology… Just going back to that point, in relation to the General Public issue of this Journal, I wanted to think some more about the anthropological project, as a project merely of observation, or what you describe as non-judgemental contemplation. However, plenty of anthropologists are quite emotionally involved in their subject, like Tsing or Taussig, and the general idea that science is unemotional work, resting purely on logic and empirical parameters is falling apart, in Europe particularly under the philosophical scrutiny of Bruno Latour and many others. Science is now, to put it non-ironically, revealed, as merely one more way of articulating the present, another way of storytelling. I am interested in what you seem to be re-visiting behind the term “politics”. Where do you see yourself or your work in relation to the public, or, your role in society as a filmmaker?

C: If the image is what’s at the center, connecting Swiss banks, [ed: their aesthetic and function], to Instagram, it’s interesting to think of how the image trade got from the 19th century early capitalism to what it is now. The question now is where does the money trail lead, and who owns the channels where the pictures are being traded.

N: Right, because we could say that historically from pre-capitalist to pre-industrial societies, image exchange existed, but it has become very specific and narrowly syphoned, and then dispersed globally, operated by a very small group of people who own these channels of distribution and create algorithms.

C: Of course, yeah… But it also has to do with mass-production of images today, the sheer quantity is stunning. And the monopoly is obvious. So in my work it’s more interesting for me to think of periphery.

Regarding anthropology, I have more of a connection to that discipline through my brother, and my own relationship to academic language is… I can’t even enter into it. It may sound strange but for me what I do is primarily based on observation: I just look at people around me doing things, uttering sounds, and I just wonder when we use words like democracy and politics, and I compare the language to what I actually see, I just wonder what is the history of the words, how accurate are they in describing our present state. The word polis — greek for city, from which politics stems…

N: …side note it passed through ‘politikos’, citizen, before it arrived to mean ‘politics’ today, or public order…

C: …right but I think it’s interesting to think about the root of it, the city, what is our connection to the city, a palace where we feel contained, because the Greek idea of city, affairs of the city, — network and technology-wise is very different from what the city is today. So if the words have transitioned from the city, I think when people say it today, they mean government, or people in charge, representatives… We are surrounded by so many contents, fictions, official policies, parties, who work with these fictions (that should technically incorporate people’s opinion and identities). Then there are stories of products and sales… So in this swamp of fictions, I participate by both adding to, and listening to the swamp, giving that exchange a voice. So, yeah, I like to listen to a place, that’s my understanding of anthropology. I think that commercial, or, political narrative fiction, I feel like starting from that would be… I think these types of films already know so much, they block out something, how do I explain this… They don’t let space for what might also be there. And I like to look at that.