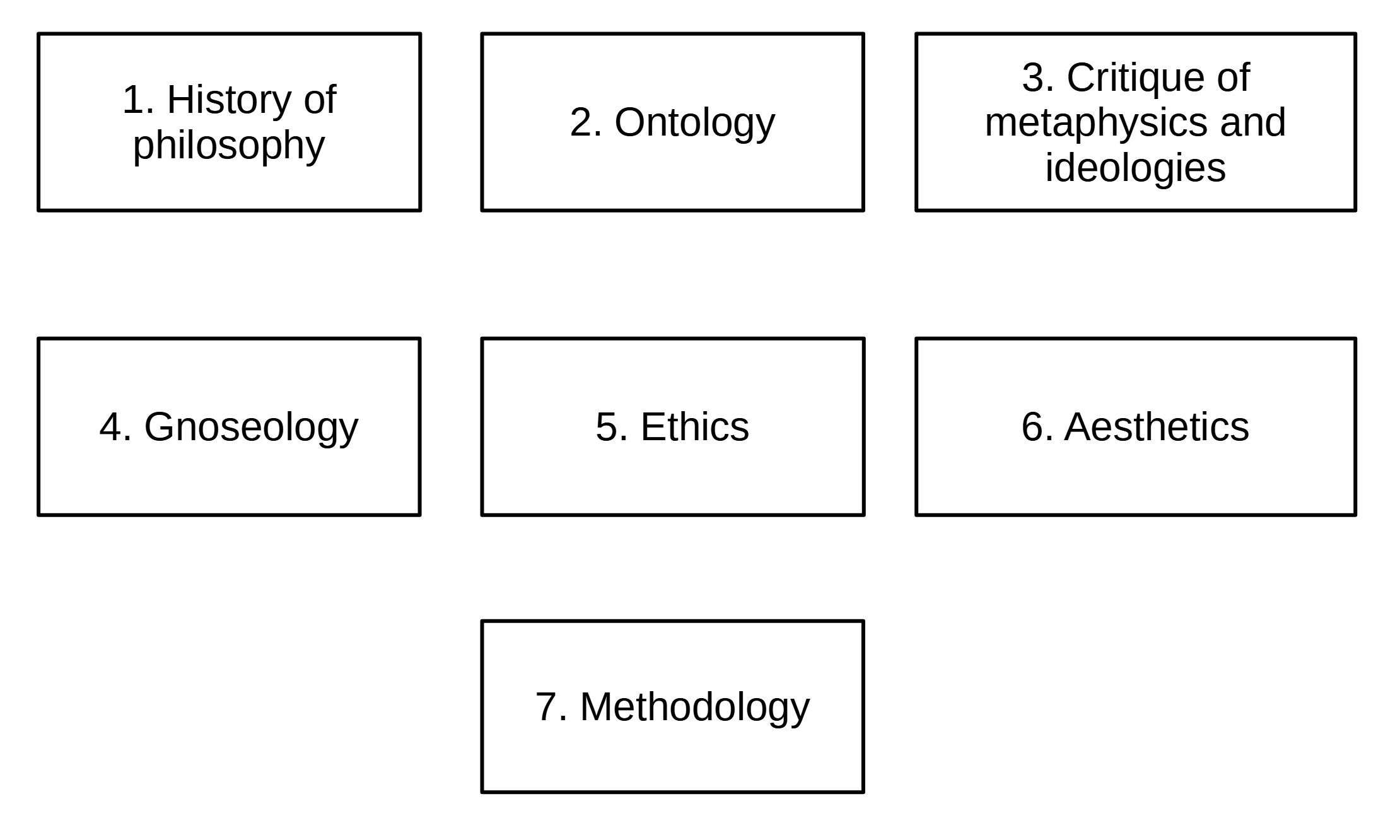

On development of materialist philosophy

- Introduction. Crisis of contemporary metaphysics

- 1. Possible expositions of the history of philosophy

- 2. On categorical system

- 3. Critique of metaphysics and ideology

- 4. On gnoseology

- 5. On ethics

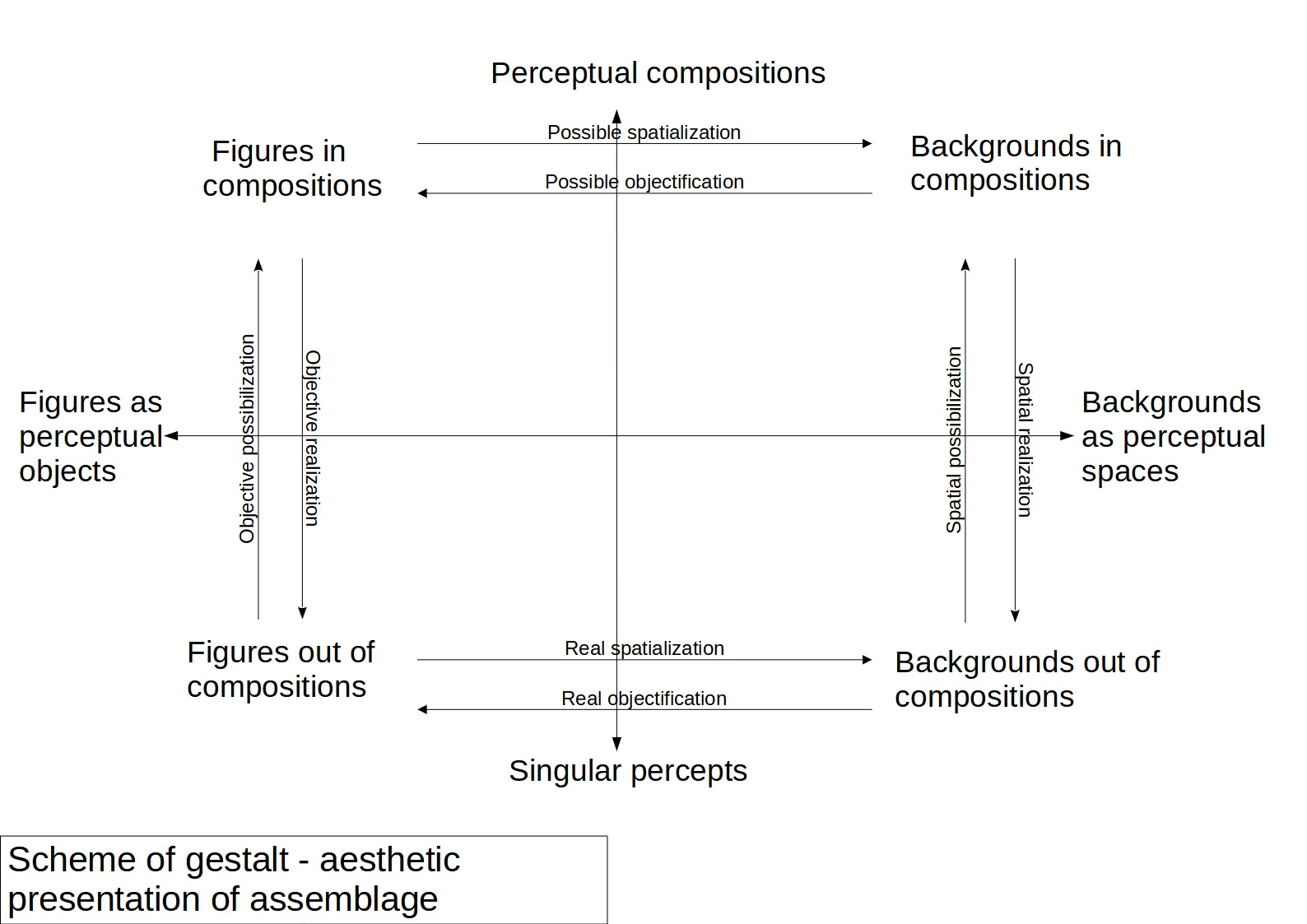

- 6. On aesthetics

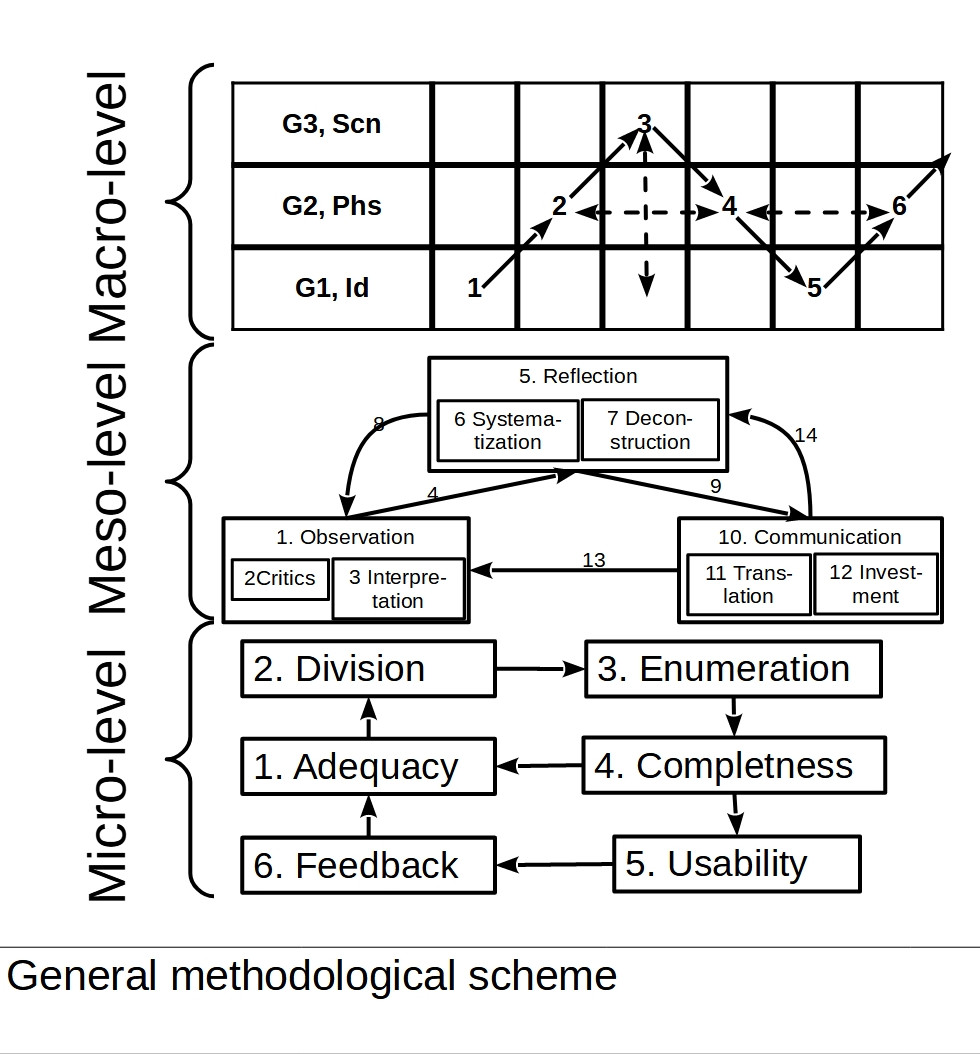

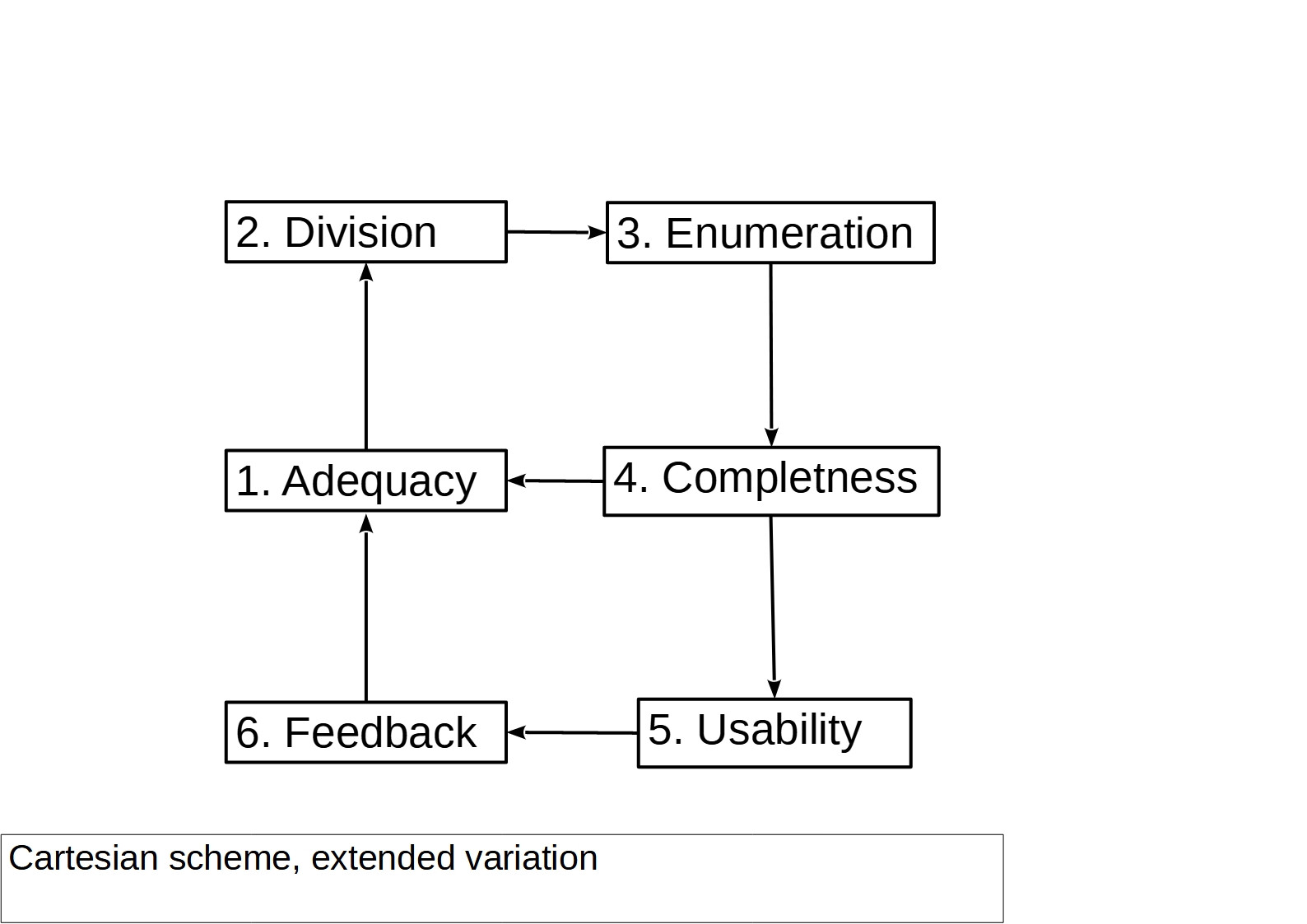

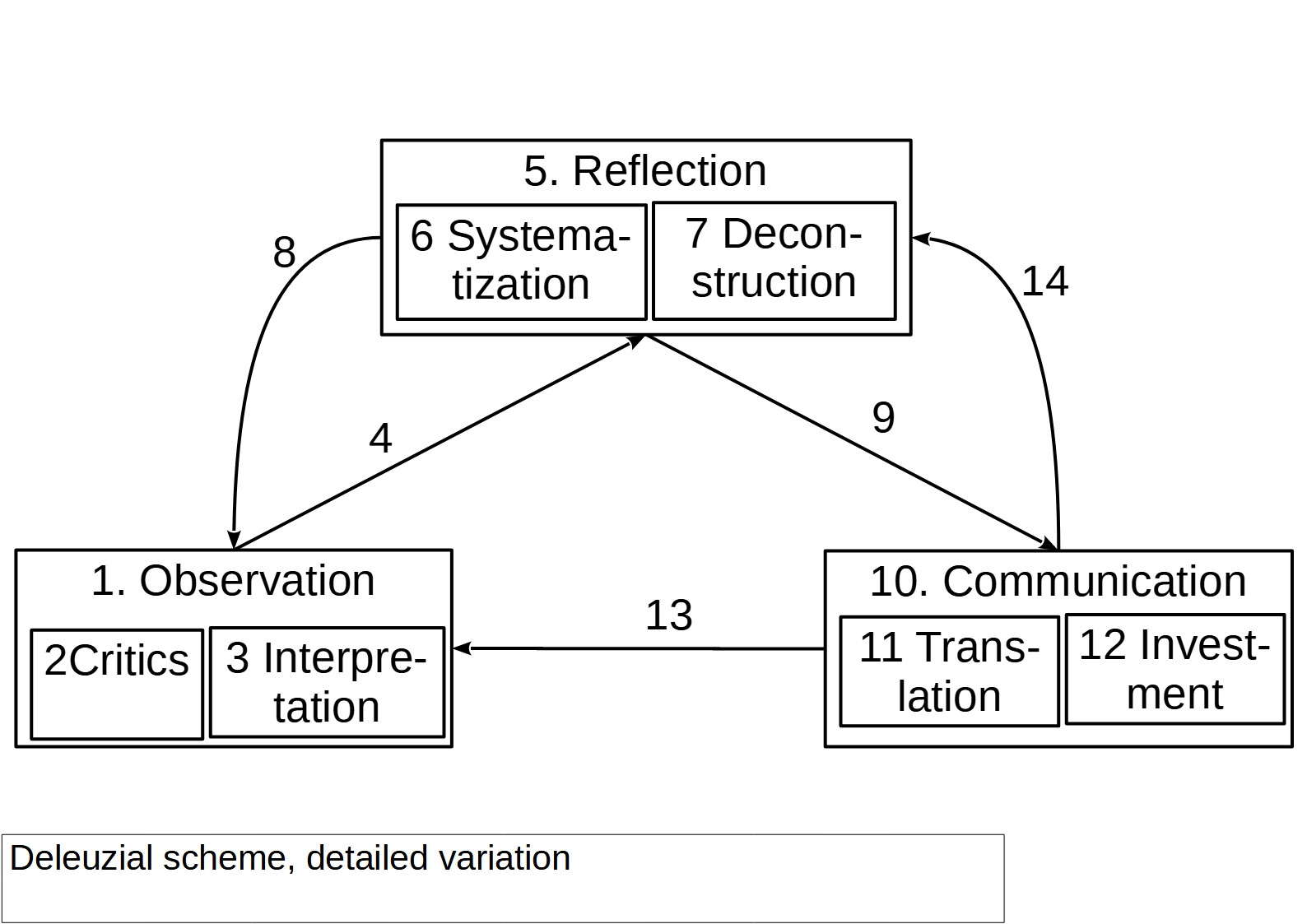

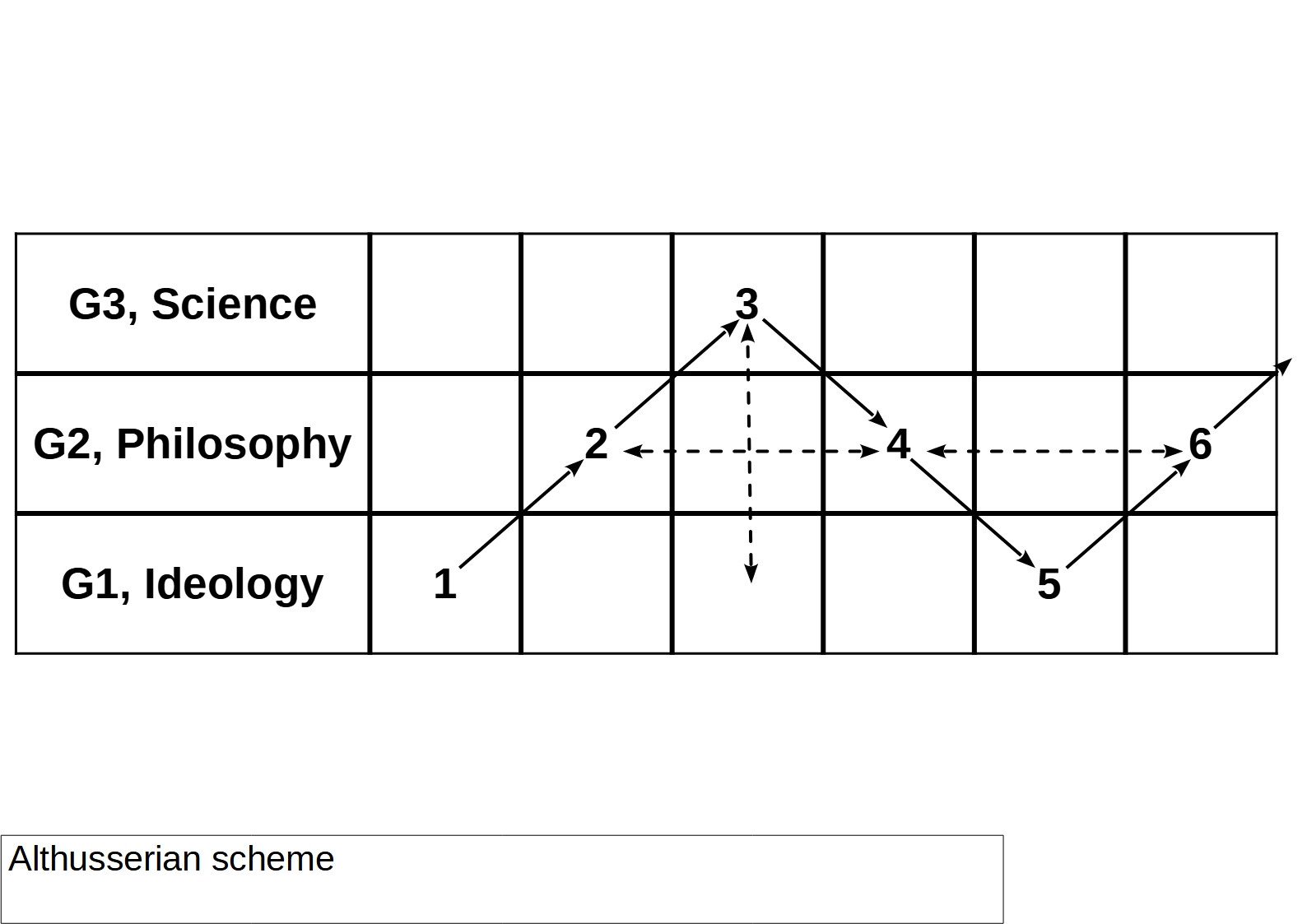

- 7. On methodology

- Conclusion: towards philosophical encyclopedia

- 1. On development of initial system

- 2. On development of derivative systems

- Bibliography

- In English

- In Russian

Introduction. Crisis of contemporary metaphysics

As noted in the Nomadology Manifesto, the most important task of adequate philosophy is the thought of sublation of the human condition of mortality and powerlessness into a posthuman condition of infinite changeability.

In this perspective, all other philosophies that do not set the task of enriching and developing society turn out to be deeply inadequate, hostile not only to our well-being, but also to our life. Their propagandists, willingly or unwillingly, turn out to be enemies of reason and progress. Let us consider these metaphysical directions in more detail:

1. Objective idealism — belief that there is some spiritual substance in addition to or instead of matter, from which thoughts, sensations, concepts, etc. supposedly consist, and which supposedly created the material world in a supernatural way. Examples: Plato, Schelling, Hegel, all religious teachings.

2. Subjective idealism — belief that the material world is generated by the individual consciousness of the philosopher who recognizes this metaphysics. Examples: Berkeley, Fichte, Husserl, and partly all humanistic ideologies.

3. Collective idealism — belief that the material universe and its laws were created by the efforts of the scientific community or humanity as a whole. Examples: Latour, Shchedrovitsky, and partly all humanistic ideologies.

4. Mechanical materialism — idea that all complex material processes are ultimately reduced to the mechanical motion of elementary particles. Examples: Newton, Holbach, Buchner, Dawkins, and in general many natural scientists.

5. Dogmatic materialism — idea that material substance is described by an undeveloped and unsystematized set of categories that developed in German classical philosophy and early Marxism. Examples are most contemporary Marxists.

6. Aleatory materialism — idea that matter exists by chance and is a multitude of separate, unique and singular objects. Examples: Althusser, Deleuze, Foucault, and most contemporary speculative realists.

7. Eclecticism is a confused, unsystematic mixture of elements of all the listed metaphysics. For example, Stalin’s philosophy was a mixture of dogmatic materialism and collective idealism; modern Anglo-American positivism, also known as “analytical philosophy,” is a mixture of all idealisms with mechanistic materialism.

Why are all the philosophies that listed strictly inadequate?

Firstly, they do not contain a correct and systematic explanation of the nature of reality — those systems that exist are erroneous, and correct ideas are not systematized;

Secondly, they lack a holistic understanding of public benefit and care about its implementation. Thus, apologists of various idealisms, having more erroneous ideas, in practice bring more harm to society than good. Whereas materialist philosophers, due to the one-sidedness of their positions, contribute to the development of society only in one relation, ignoring others binded to the first.

Thirdly, since all the listed metaphysicians do not care about liberation from human condition, then remaining in it, they will inevitably grow old, die and rot in coffins, where bacteria and worms will feed on their corpses. This means that their philosophy deserves to be buried with them.

How can an adequate philosophy be constituted that can ensure us the achievement of absolute knowledge, wealth and immortality? Let us consider this in the order methodologically determined by this philosophy itself.

1. Possible expositions of the history of philosophy

Like any theoretical practice, philosophy begins with knowledge of basic texts and terms. The history of philosophy is the most important component of the process of training future philosophers. Without knowledge of the ideas expressed by philosophers in previous eras, it is impossible to advance further in its development; and without a clear and distinct understanding of regularities that generate this knowledge, confusion and unsystematiness are inevitable, dominating in most philosophical movements to this day. In other words, it is impossible to become a good philosopher without mastering what was accumulated by our predecessors over the 2.5 thousand years of the existence of philosophy, despite the fact that in mastering we must be guided by a method that allows us to rank philosophers and their ideas by importance, which is what university students also do philosophers, but without understanding the criteria of significance.

Apart from the pathos and euphemisms, it is obvious that the real criterion for the significance of certain philosophers and concepts in academic philosophy is their harmlessness for the ruling class. Why do Russian handbooks of philosophy devote a great deal of time to the study of the ancient Greeks, patristics and scholastics, Kant, Nietzsche, phenomenology and hermeneutics, existentialism, and especially Russian religious philosophy? Because the ideas of these authors either have an extremely weak connectioning with the surrounding reality of material production and class conflict — or because they directly justify the existing state of affairs. Let’s open Berdyaev, Florensky or Ilyin on any page — everywhere they sing praises to the institutions of family, private property and the state as eternal divinely inspired institutions — although half a century earlier, somebody Friedrich Engels scientifically proved their historicity — that is, that they once arose, and once will cease to exist. In Western universities, there is a dominance of the so-called “analytical philosophy” — that is, a form of professional solipsism, the adherents of which seek to divert the thoughts of future scientists and philosophers from the study of material reality and its contradictions into the jungle of formal logic, from which its rational grain and the possibility of practical applications. In a word, the matter usually does not come to the study of philosophers who investigated and solved real problems useful both for understanding philosophy itself and for political, scientific and artistic practice.

Another unforgivable mistake when presenting the history of philosophy is to consider individual philosophers and their concepts without the relationship of their ideas with each other and with that social reality, which is the basis of all philosophical and scientific thinking.

Indeed, the personalistic account of the history of ideas, taken for granted, actually hides a dilemma: either the cause of the emergence of ideas is the very personality of the individual subject, be it the soul or the brain, which has no cause except itself — or the body of the writing or speaking philosopher is only a passageway for cultural and social processes that do not originate or end in the brain of an individual person.

The first concept is metaphysical, idealistic and anti-scientific, as it contradicts the principle of causality. The second is adequate to the reality around us. This means that the meaning of scientific teaching of philosophy is not to dwell on the personalities of certain philosophers, but to go further to those impersonal social forces that expressed themselves through them in any previous eras in one way or another — in order to understand the patterns of development and follow them in one’s practice .

In this regard, two good textbooks can be cited as starting points for thought:

Firstly, the Soviet six-volume "History of Philosophy" ed. Dynnik, 1957-65. — a good edition that covering next topics:

The first volume gives the history of philosophy from Antiquity to German classical philosophy;

The second volume gives the history of philosophy of the 18th and 19th centuries;

The third volume is devoted to the discovery of historical and dialectical materialism by Marx and Engels, as well as the cultural context in which this discovery was made;

The fourth volume is devoted to the philosophy of the peoples of the world in the second half of the 19th century and the spread of Marxism;

The fifth volume tells about the triumph of Marxism during the October Revolution, the activities of Lenin and the further spread of Marxism throughout the planet;

The sixth volume, published in two books, is devoted to the development of Marxist and non-Marxist philosophy after the October Revolution, respectively.

The advantage of this work, as well as Marxist philosophical historiography in general, is its systematic nature and adequate emphasis. The combination of philosophy with social science and politics in Marxism was the most important evolutionary leap in the development of philosophical thought, which allowed communist and materialist ideas to embrace wide sections of the population, accelerating the course of world history. Consideration of previous philosophical teachings by eras, as well as ranking by proximity or hostility towards progressive social and scientific trends — was and remains a significant achievement in the methodology of presenting the history of philosophy, which should be developed and regulated in accordance with the development of the same dialectical method — that is, on its own basis.

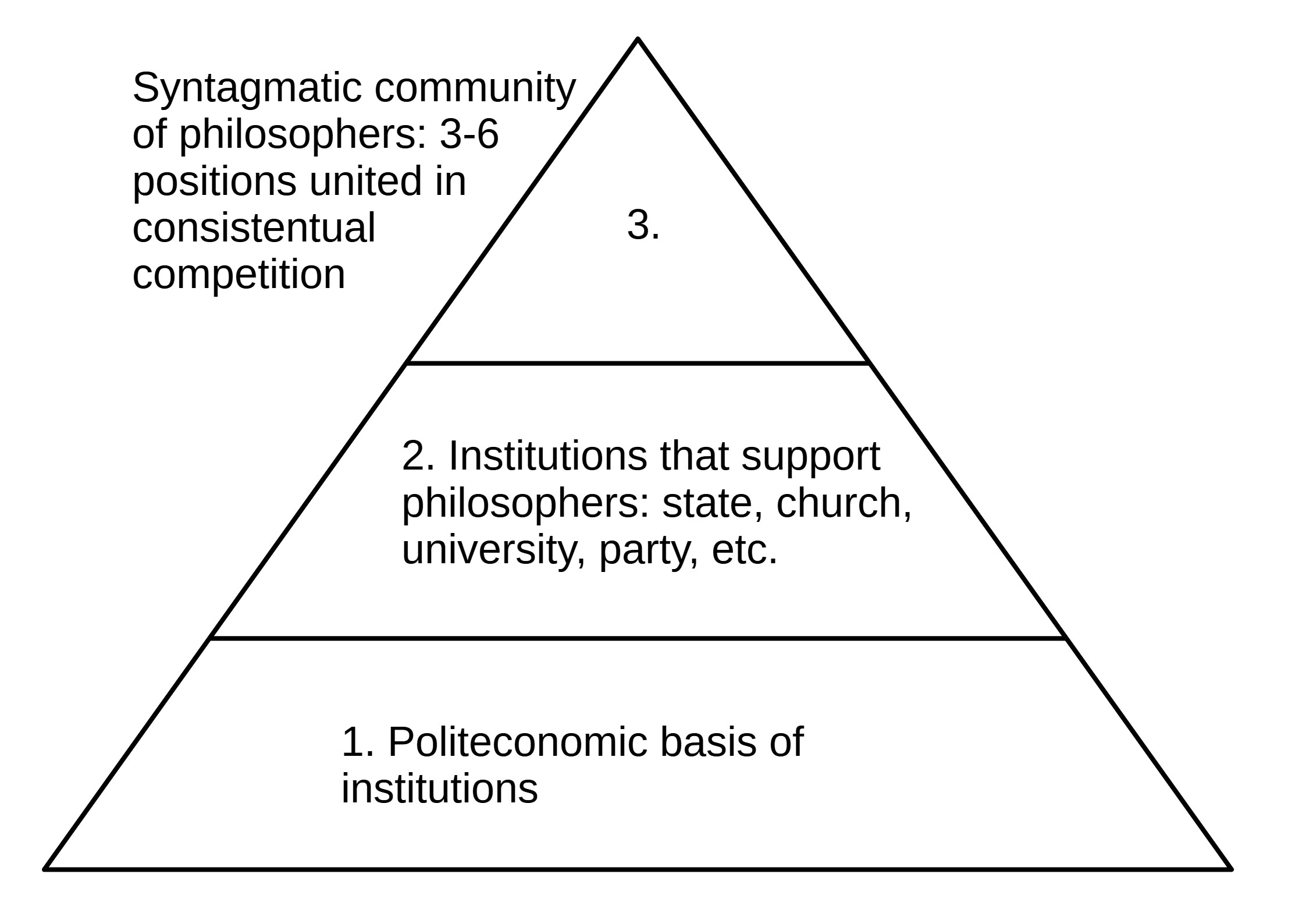

It is not difficult to be convinced that this presentation can and should be improved by studying another starting work, namely, “The Sociology of Philosophies” by Randall Collins. Like the Marxists, Collins agrees that the movement of philosophical matter cannot be explained by the personalities of individual subjects, but that the chains of cause and effect, expressed at some point in their implementation in philosophical speeches and treatises, extend over thousands of kilometers and tens of generations over the limits of the bodies of individual carriers. The advantage of his work is the greater detail of the mechanism of social determination. In his opinion, there are three levels of organization of the machine of philosophical thinking:

1. The production basis of society, giving rise to certain organizations and ideas as an expression of economic contradictions;

2. Organizational basis of the community: church, university, party, etc. — something that ensures the material existence of intellectuals, gives them a livelihood and free time to discuss and develop ideas;

3. A community of intellectuals who are in close personal communication, in which three to six competing positions are distinguished, superstructure over politeconomic relations and social institutions.

For example, in the mid-19th century there was an intellectual network of left-wing Hegelians that relied on the German university as its organizational basis. Subsequently, young Marx and Engels left it, replacing the university with a political organization — Bund des Communisten, thanks to which they made their doctrine international. While the basis that allowed some intellectuals to remain at the university, and others to develop within the framework of a political organization expressing the interests of the working class, was and remains capitalist commodity-money production, from which university philosophy remains alienated, since outside of an alliance with the working class it is not able to influence basic economic processes that constitute the conditions of its own existence.

At the same time, Collins himself does not bring this scheme to fruition, and in general his neglect of the achievements of Marxism has especially negative effect in the last part of his book, when he moves on to an analysis of the philosophy of the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. In it, he focuses entirely on the “university revolution” — that is, the establishment of a strong connection between philosophy and the university as its organizational basis, ignoring the existence in the same period of an alternative, party basis for philosophical activity. As a result, among the “great philosophers” of the early 20th century he includes such almost useless, and in many ways harmful to us, figures as Russell, Frege, Wittgenstein, Carnap, and the like. The usefulness of philosophy for liberation politics, social sciences and natural science tends to zero.

Thus, as starting points, we have two major works outlining the division of the subject at the macro and micro levels respectively. The further step in the development of a materialist understanding of the history of philosophy must be a synthesis between these two opposing positions, correcting the significant lacks of both works.

The point is that in both works, which describe a specific ontology of the history of philosophy in semi-formal terms, there is no relation to the work of categorizing the entities of a universal ontology as the heart of philosophical knowledge. Moreover, for the Soviet textbook this opportunity was quite tangible, since the subject of study of the Marxist philosophers, whose activities are described in the six-volume book, was materialist dialectics as the best existing prototype of universal ontology. Therefore, it would be logical to expect that the movement of social matter in the form of philosophical groups that developed certain concepts should be described in the categories and laws of materialist dialectics. Similarly, Collins, given his intellectual context, might have been expected to use, if not dialectical categories, then at least an expanded set of methods and concepts from systems theory, with which he was undoubtedly familiar.

Another drawback of both works is the absence or lack of practical conclusions regarding the applicability of philosophy for criticizing dominant ideologies, developing scientific paradigms, solving ethical and political issues, problems of aesthetics and general philosophical methodology. The question of the interconnection of this topics with the history of philosophy formed the basis of the plan of this article.

Be that as it may, solving the problem of mutual correction of both ways of presenting the history of philosophy is possible in the light of constructing a system of categories, the needs of which make it possible to rank philosophical trends in order of importance.

2. On categorical system

The history of philosophy and the system of ontological categories are closely interconnected. On the one hand, we need the history of philosophy in order to form the most adequate ontology from multiplicity of possible, based on the developments of the greatest thinkers. On the other hand, the history of philosophy itself must be described in the same ontological categories that we draw from it. Are we not falling into a vicious circle? In fact, the circle opens into a spiral of upward development due to the verification of the adequacy of our ontology in related areas — critique, gnoseology, ethics and aesthetics, due to which ontology acquires methodological significance for the self-development of the philosophical discipline.

In general, a cycle that includes moments of emerging assemblage, optimization and deconstruction of meaning systems is the very essence of philosophical practice. Such an expansion of Deleuze’s hypothesis about philosophy as the invention of concepts, as we will see below, is quite legitimate, and moreover, directly follows from his own metaphilosophical works.

In fact, the history of philosophy appears before us as a huge accumulation of concepts and conceptual systems. Every subsequent systematic is faced with the task of selection and prioritization. At the same time, the priorities of choice cannot be taken “out of thin air” or from the requirements of an arbitrary part of the audience, but must be derived from all totality of a consistent philosophy. However, as with the history of philosophy, we are faced with the question: where to begin? From dozens of philosophical schools and hundreds of major philosophers, how can we choose those that are most suitable for us?

In practice, this problem is solved easier than you might think. So, first we should discard most of the philosophers who dealt with particular issues and did not have a clear methodology — they are not suitable for us. Then discard the philosophers who had confused, metaphysical and idealistic systems — clearly anti-scientific nonsense will not help us to build a philosophical basis for the scientific picture of the world. Finally, from the remaining physicists and materialists, one should select those whose categorical apparatus allows us to give the most complete, comprehensive and simple description of reality on the basis of universal principles applicable to all possible forms of motion of matter.

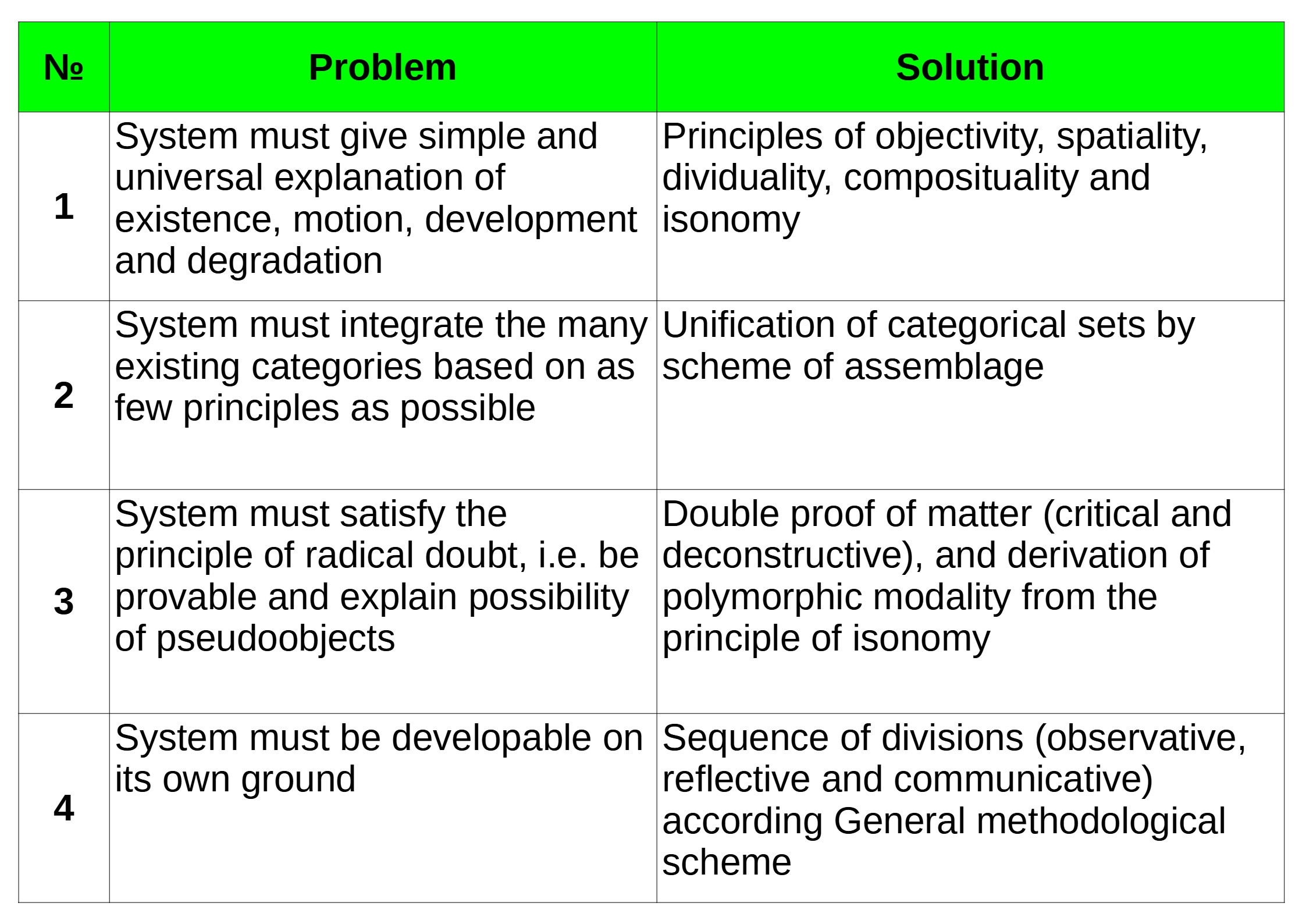

In other words, we already have a certain initial materialistic intuition that precedes the formation of the system and is recognized in the form of problems and principles. We list these principles in the form of the following table:

Indeed. The observable and conceivable variety of forms of motion presupposes the presence of both moving objects and spaces in which motion occurs. As Friedrich Engels rightly noted:

"Motion is the mode of existence of matter. Never anywhere has there been matter without motion, nor can there be. <…> Matter without motion is just as inconceivable as motion without matter. Motion is therefore as uncreatable and indestructible as matter itself" F. Engels, Anti-Duhring, ch.6

The concept of assemblage, constituted by the principles of objectivity and spatiality, dividuality and composituality, causality and effectuality, etc. represents a universal way of dividing observable and conceivable reality so that it can be divided uniformly in any of its manifestations while maintaining the possibility of movement, development and degradation. This eliminates the anti-scientific and metaphysical idea that reality is not divided uniformly, but into arbitrarily chosen asymmetrical groups of objects, for example, the creator god and the created world in theism; or active/conscious people and everything else. With the same success one could divide everything that exists into many sofas — and all other things. Such an armchair ontology would be as arbitrary as theocentric or anthropocentric, vestiges of which still persist in public culture.

On the other hand, since objects and spaces, elements and systems, causes and effects limit each other in all possible directions, then this mutual limitation itself is necessarily limitless. The innumerability of all possible assemblages, the infinity and eternity of their totality, already in ancient materialism was conceptualized as nature or isonomy — the reality of all possible.

These two poles of the system are assemblage and nature are devoted set the initial alignment of historical and philosophical material, considered as the most relevant for building the system:

1. Ancient atomism of Democritus, Epicurus and Lucretius — the original materialist ontology, describing reality in terms of the combinatorics of atoms and voids that form nature as isonomy — the reality of all possible.

2. Deleuzo-Guattarian materialism of assemblages allows us to conceptualize the process of connecting and disconnecting of the particles and voids as a key concept of the materialist system — assemblage, freed from ancient reductionism.

3. The ontological branch of Soviet dialectical materialism expands the set of categories and outlines the figurative ordering of the conceptual field. The conception of the Leningrad ontological school “Thing-property-relation” allows us to organize a large number of groups of categories developed in the history of philosophy, correlating with each other as aspects of the assemblage; while many other, more complex concepts are captured in a more concrete dialectic of process that builds on top of the concept of assemblage and its extensions. Also in the works of Tugarinov and Orlov, an analysis of the concept of matter as a substance is outlined, a distinction is introduced between extensive and intensive definitions of substance — nature as an infinite set of objects and as the space of their eternal combinatorics, respectively.

Based on this initial given, further selection is possible for the compossibility of all other authors, concepts and conceptual systems given to us by the history of philosophy — which in turn is reflected in the presentation of the history of philosophy, in the placement of emphasis, which authors we consider necessary to highlight and consider in more detail, and from which to abstract as unimportant.

Further ordering of conceptual material involves division into the dialectics of a thing and the dialectics of a process. In “Anti-Dühring”, in “Dialectics of Nature” and in a number of other works, Engels writes that modern natural science increasingly views phenomena not as stationary isolated things or objects, but in motion, as processes. But the opposite is also true: the process as a continuous process of change exists and is conceived only as a variety of discrete interactions of individual elements. Thus, the basis of the dialectical worldview is the dialectic of discrete and continuous, thing and process. This is obvious to any reader familiar with the texts of Engels, Lenin, and the main Soviet works on dialectical materialism. Therefore, within the framework of this article there is no need to dwell on this issue in detail. At the same time, within the framework of critique of vulgar Deleuzianism and Ilyenkovism, whose representatives introduce confusion into the subject of materialist dialectics, and also deny the significant achievements of Soviet philosophy, its applicability in the natural and social sciences, which is generally superior to that in the works of Deleuze, Ilyenkov and their followers, then In the future, one or more works should be devoted to clarifying this issue.

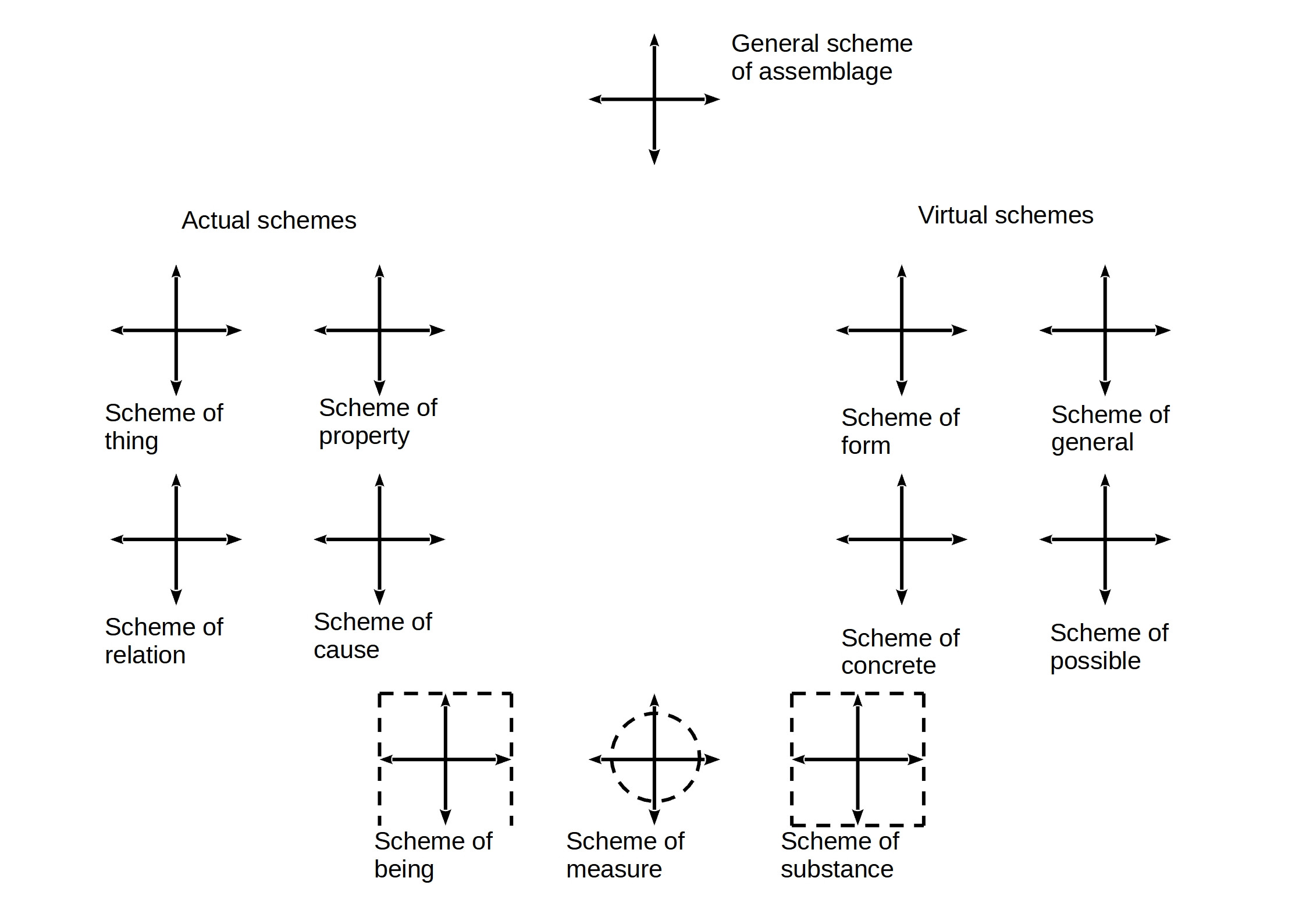

However, our methodology in this regard is able to immediately present a brief and comprehensive answer to the claims of some eclectics regarding the imaginary dogmatism of Soviet philosophy in the form of the following scheme:

The conception "Thing-property-relation" mentioned above allows us to use the figure of the assemblage to systematize groups of categories of dialectical materialism. Extensive categorical material, which is of key importance for the construction of ontologies of specific assemblages, but remains not covered by the thoughts of vulgar Deleuzians and Ilyenkovists, clearly and distinctly demonstrates the superiority of dialectical-materialist systematization over haphazard, incoherent attempts at conceptualization.

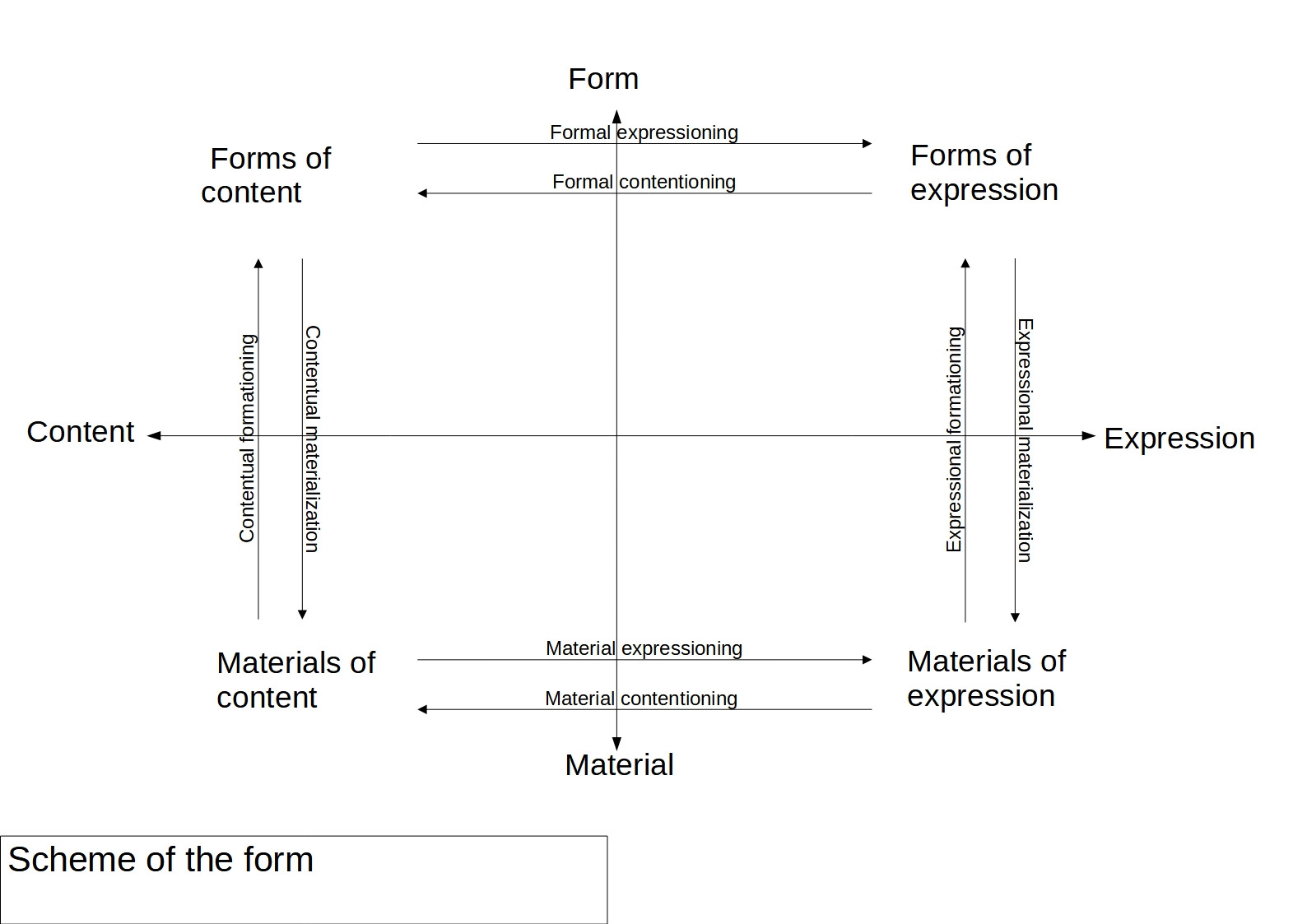

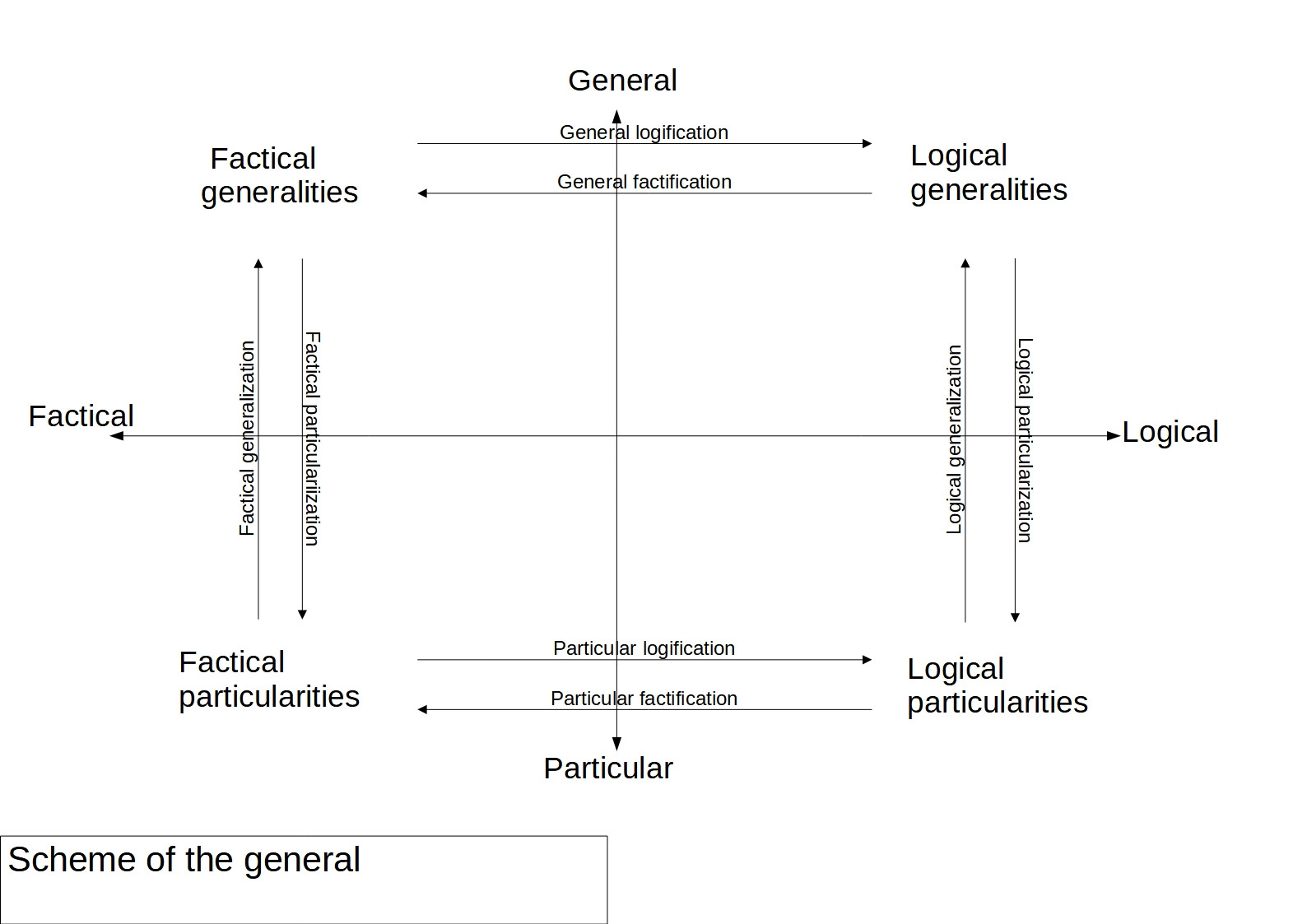

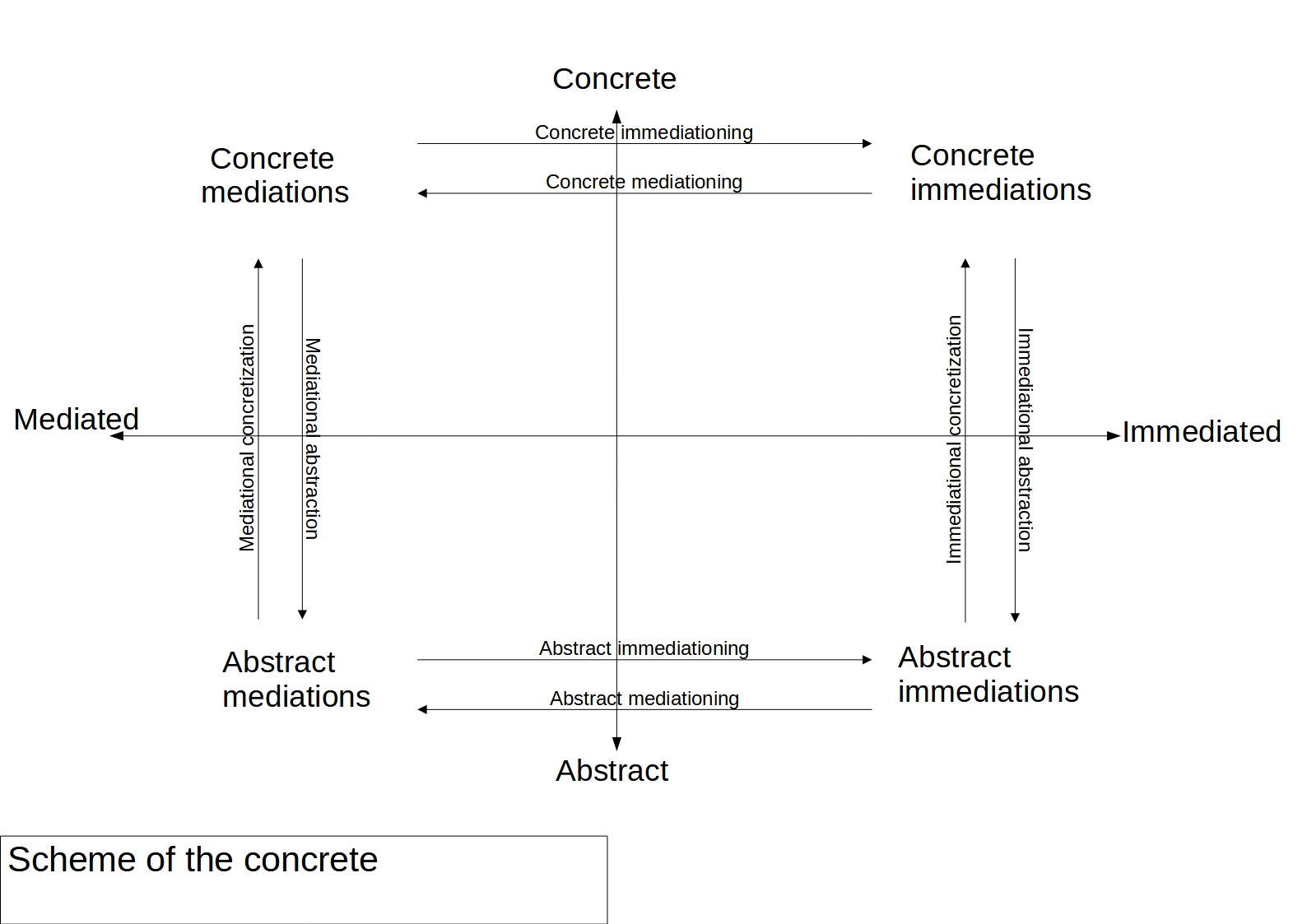

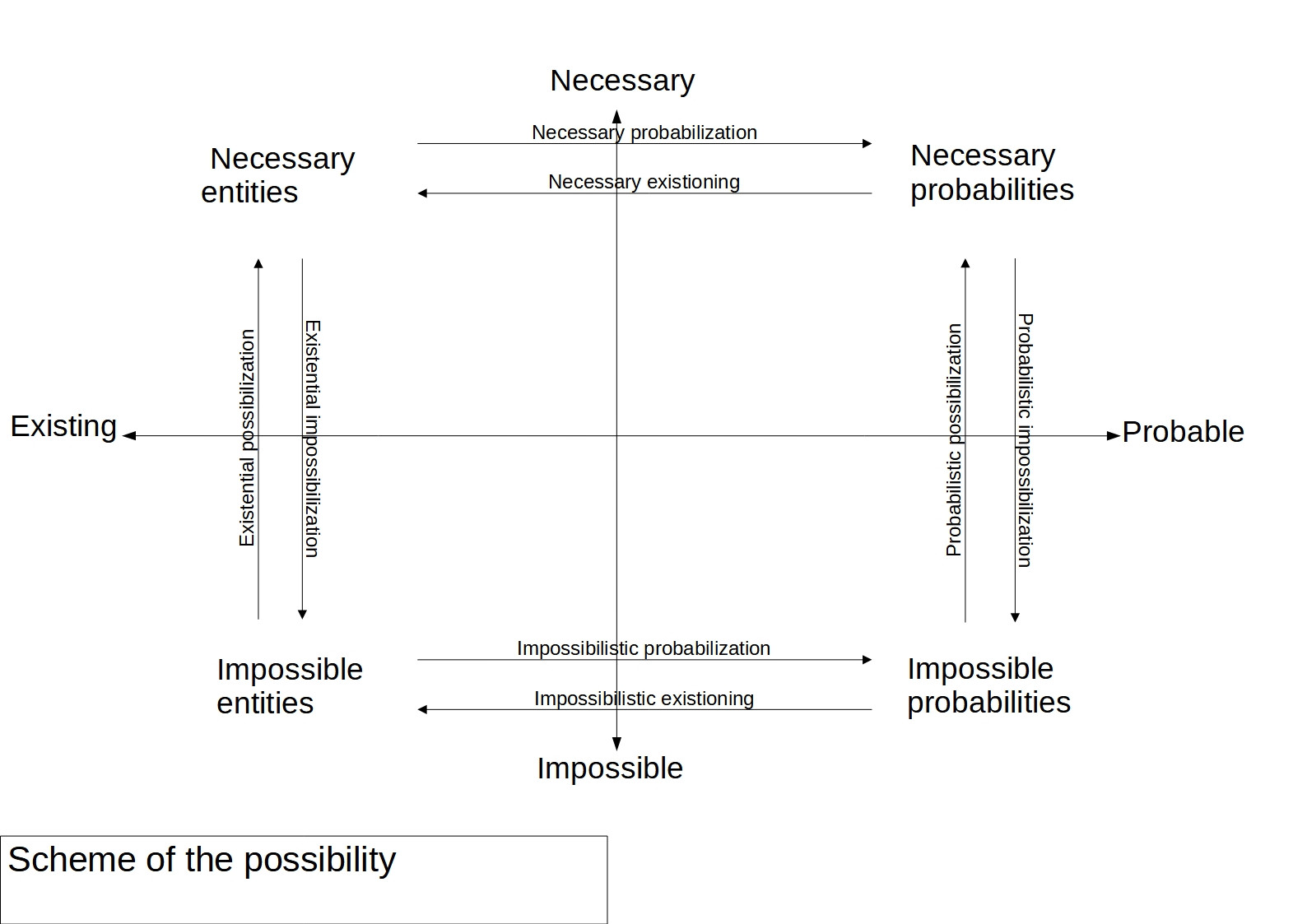

In each of the subscheme, the general assemblage scheme with which my readers are already familiar is modified in relation to a specific group of categories. Let’s look at them in more detail:

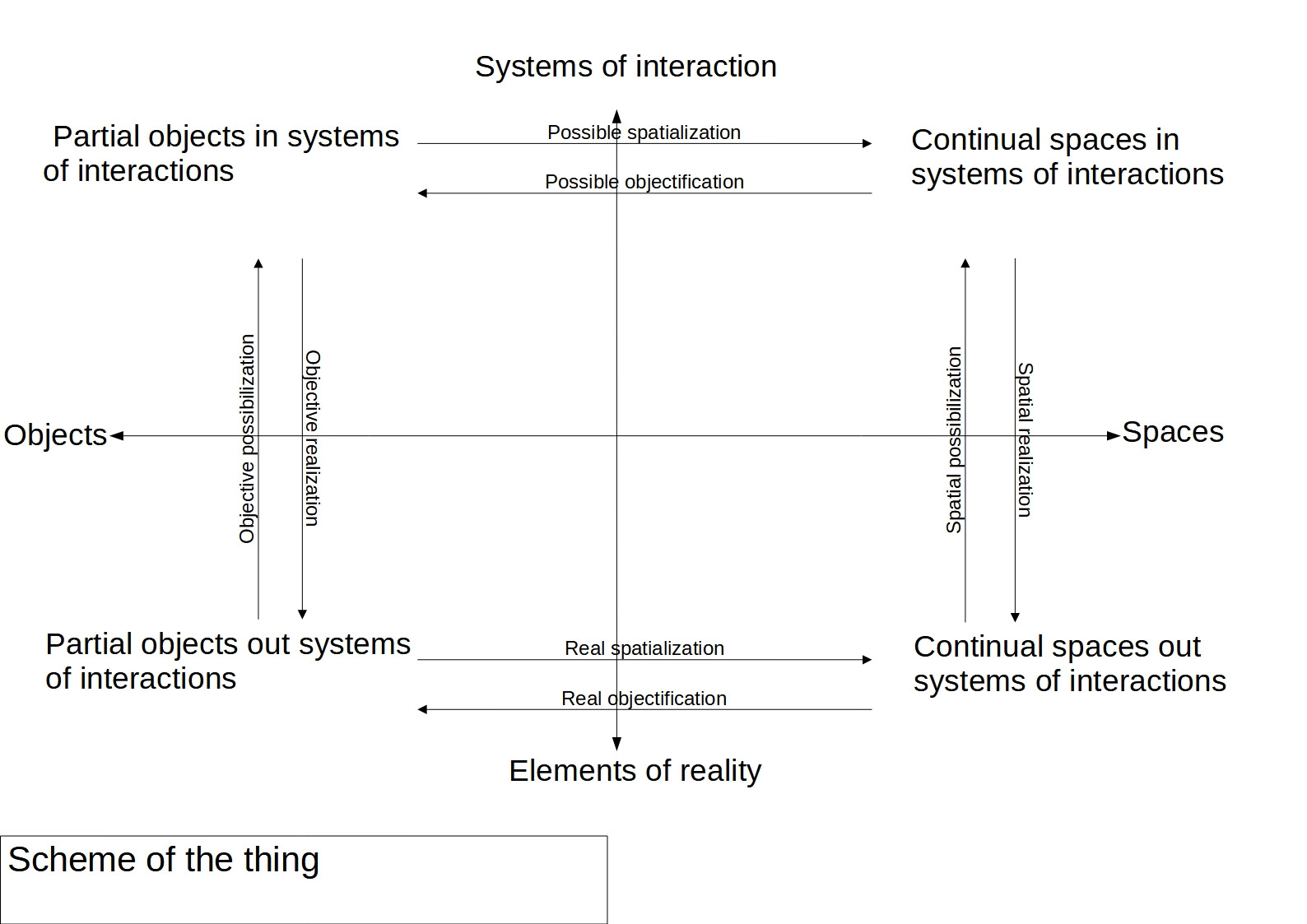

1. The scheme of thing describes any mode of substance as an assemblage — a process of connecting and disconnecting objects and spaces that exist separately and in systems of interaction. This is how any specific objects are described — atoms, tables, social institutions, galaxies, linguistic systems — anything. Further figures describe the same concrete assemblages, but in different aspects.

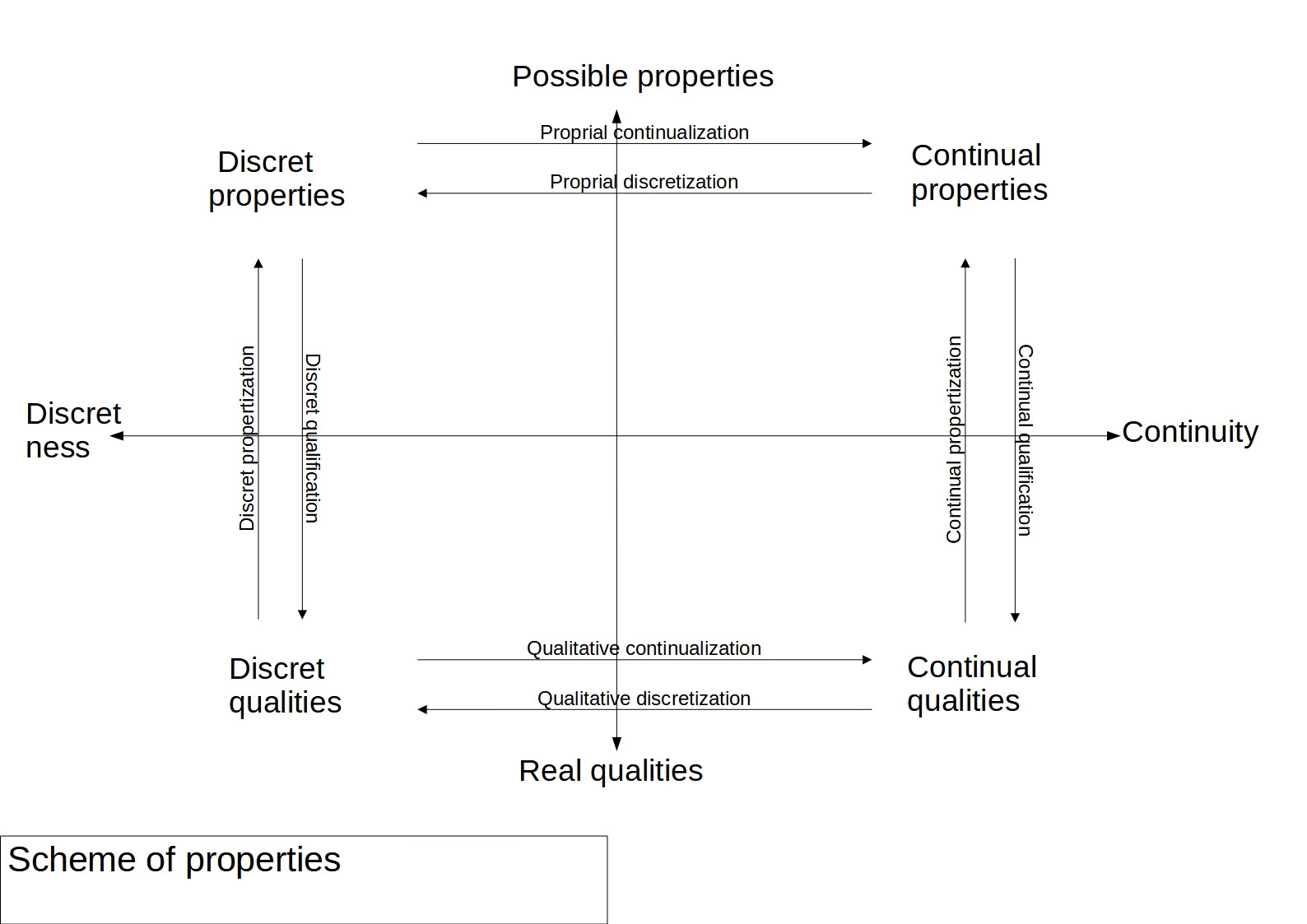

2. The scheme of properties describes the most general certainties of any assemblage as unity, difference and the possibility of mutual transition between discrete and continuous determinations inherent in things separately and in systems of interaction. In this way, the new European problem of primary and secondary qualities, raised by John Locke and which received a rather specific and in many ways dead-end development in Britain empiricism, is solved.

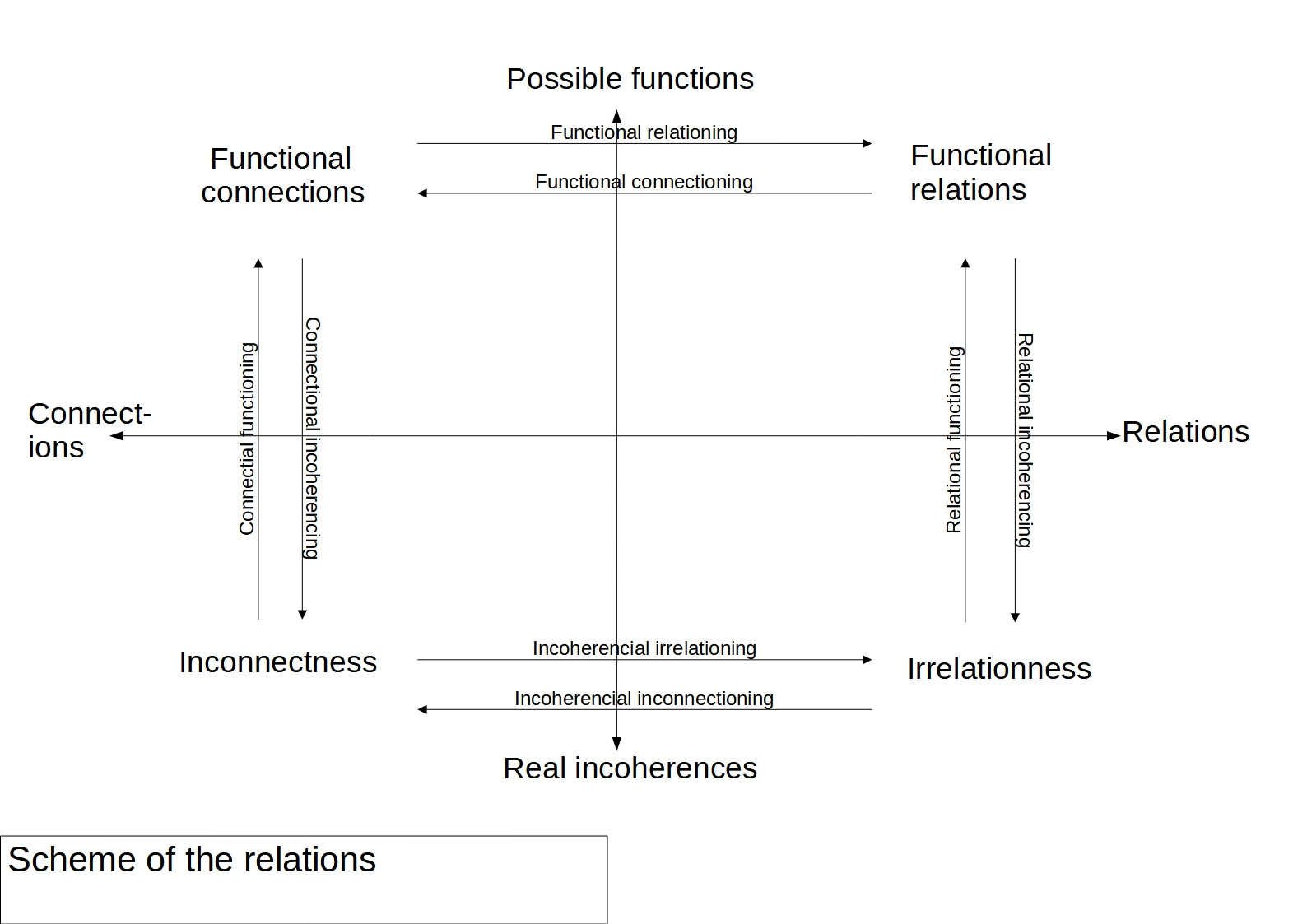

3. The scheme of relation describes the mutual determination of various assemblages in spatial and logical aspects in the spectrum from incoherence to functional dependence between spatial and logical movement — energetic and informatic processes. In this way, the problem of the difference and relation between the logical and the spatial, posed in the philosophy of Descartes in the form of a metaphysical doctrine of two substances, is solved.

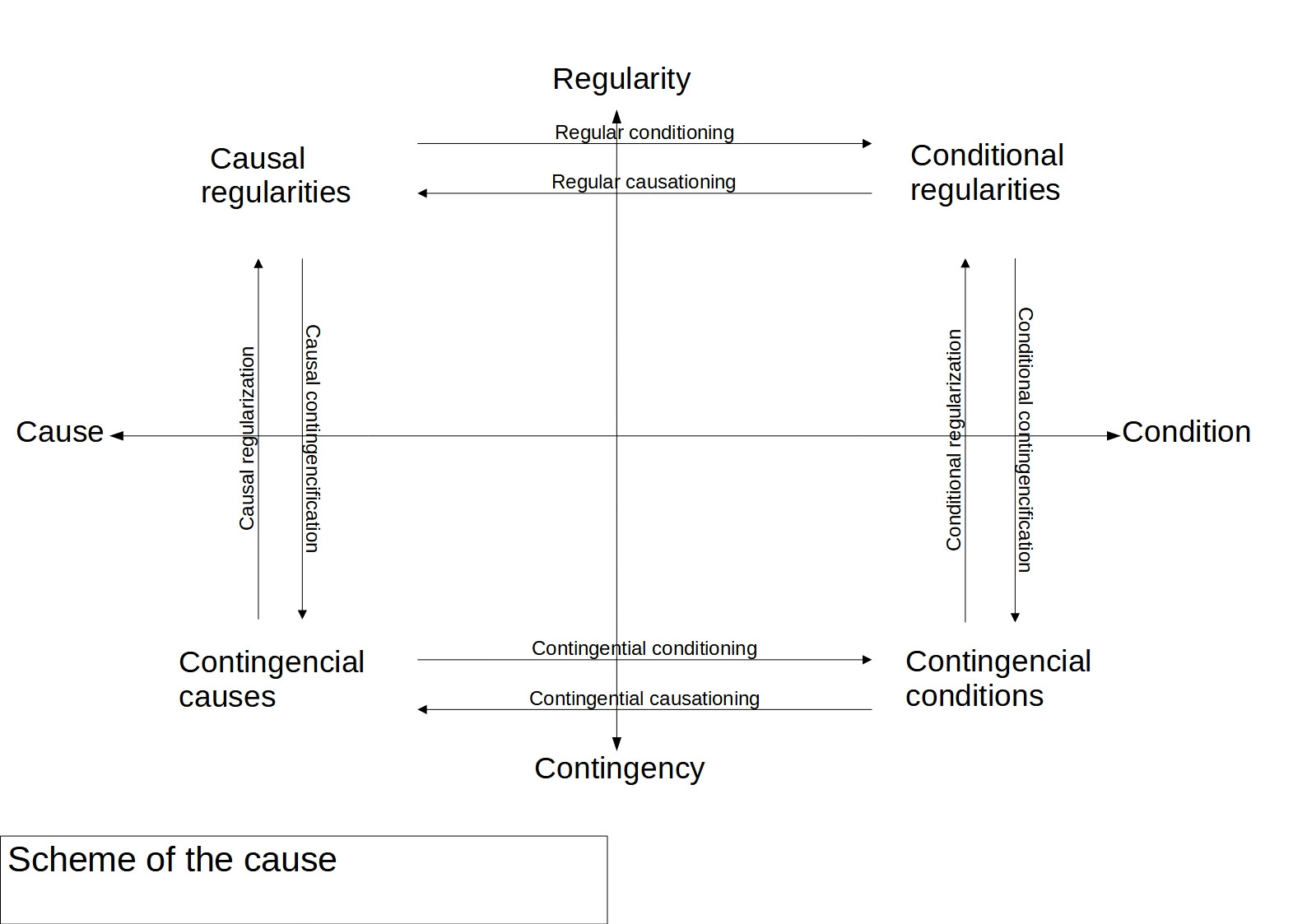

4. The scheme of cause describes the third axis of the assemblage, the transition from causes to effects, establishing a distinction between causes as actual figurative factors that generate certain effects — and conditions as virtual background factors indirectly involved in the generation of effects. Here the problem of the relationship between contingency and regularity is solved — the first of them represents an incoherent set of causes and conditions that produce certain consequences; the second is the totality of causes and consequences brought into the system. And since in reality, connected and incoherent components of assemblages always coexist, their motion reveals everywhere a dialectic of regularity and contingency, surpassing both the idealistic absolutization of regularity in Plato’s metaphysics and the absolutization of contingency as hyperchaos in Meillassoux’s metaphysics.

The four previous schemes describe any actual assemblages, so they are easy to understand and remember, associated with visual examples of concrete things, their properties, relations between them, and the causes of their emergence. The four subsequent schemes are more virtual, describing the universal properties of matter that allow certain specific assemblages to emerge. Nevertheless, the concepts organized in them have already been discussed many times in the scientific and philosophical literature, so understanding and remembering them for an attentive reader will also not be difficult.

5. The scheme of form describes the relations between form and material as the surface and depth of any assemblage that emerge in the process of connecting and disconnecting of the elements that consist of the system, respectively. Content and expression describes the objective and meaning configuration of surfaces and depths that change in the process of any assemblage. For language systems, the dialectics of form, material, content and expression was explored by the Danish linguist Louis Hjelmslev in the treatise “Prolegomena to the Theory of Language”, and was further generalized by Deleuze and Guattari starting from the third chapter of “A Thousand Plateaus” as a universal description of the possible forms of motion of matter.

6. The scheme of general describes the relationship between the general and the particular, as emerge as a result of the processes of connection and disconnection of elements of systems, taken in factual and logical aspects. This achieves an adequate solution to the medieval problem of universals, first outlined in the works of Plato, Aristotle and Democritus, and which plays an important role in contemporary philosophy. Misunderstanding of the materialist dialectic of the general and the particular leads many philosophers and researchers into the jungle of metaphysics, be it Lyotardian postmodernism or Anglo-American positivism, both of which deviate into the nominalistic absolutization of the particular, which completely undermines the applicability of their philosophical constructs in science, politics, art and philosophical methodology itself.

7. The scheme of concrete describes the classical dialectic of the mutual transition of the abstract and the concrete, taken in relation to immediacy and mediation, which found its most complete expression in the four volumes of Marx’s Capital. A number of “Capital” researchers, such as Althusser, Ilyenkov or Vazyulin, either underestimated this dialectic or gave it a one-sided interpretation, which, unlike our interpretation, was not included in a more extensive categorical network.

8. The scheme of possibility clarifies the dialectic of the necessary, impossible, existing and probable. In fact, every assemblage includes a moment of the actually existing and the probable virtual, which mutually transform into each other, starting from the pole of the impossible, non-composite, to the pole of the necessary, consisting of an infinite number of components and probabilities. Moreover, since necessity and impossibility in specific assemblies are relative, it is possible to talk about impossible (in a given system) entities and probabilities that may exist in another system. This outlines an approach to solving the Leibnizian problem of possible worlds.

The eight preceding schemes are simple extensions of the assemblage scheme: four actual and four virtual extensions. The three subsequent schemes have some differences in construction, emerge from the meaning of the schematized groups of categories, which are also easy to understand, since they refer to a number of classical philosophical problems.

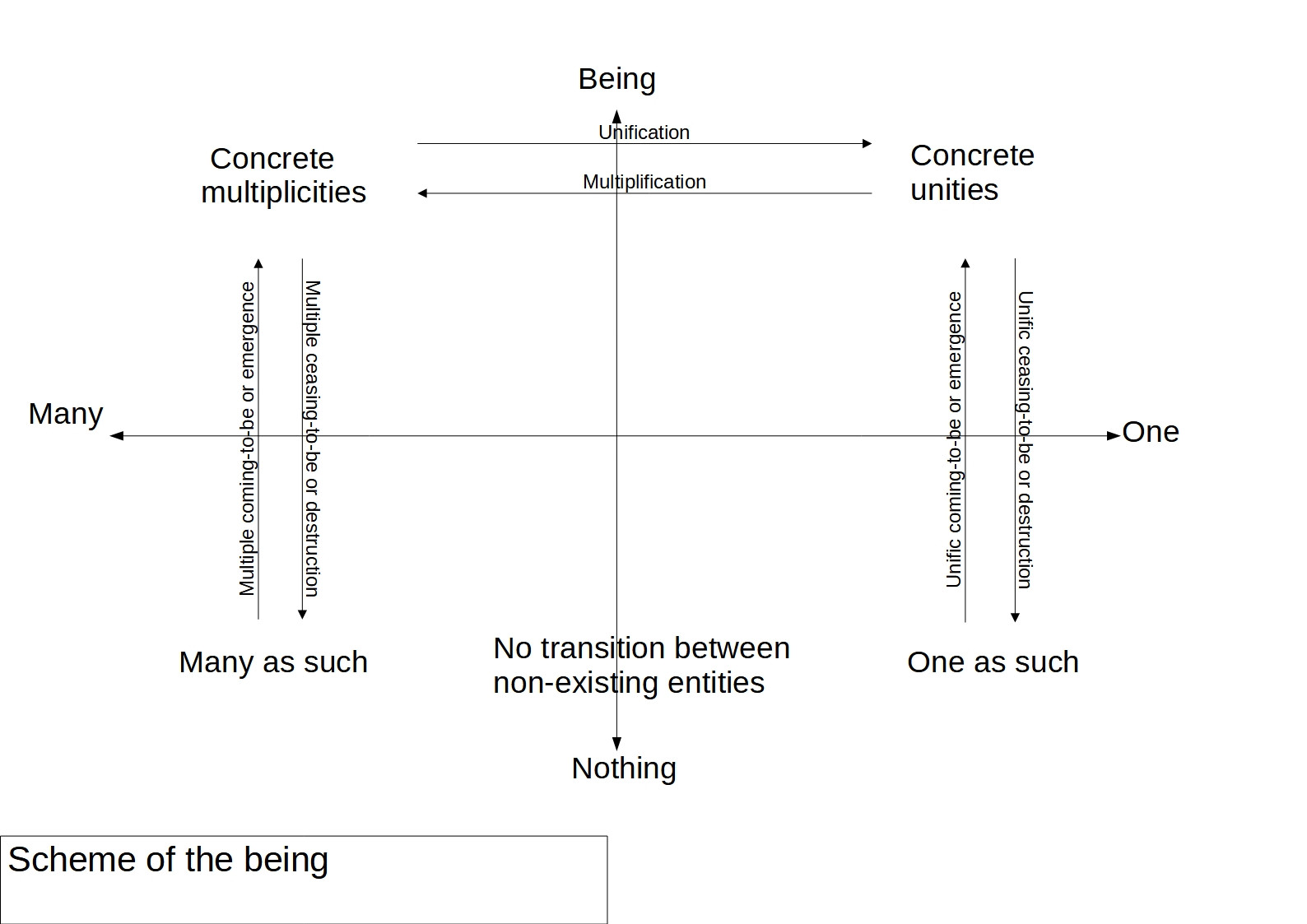

9. The scheme of being describes the dialectic of being, nothing, one and many, presented in Plato’s Parmenides. The difference between this scheme and the previous ones is due to the fact that the non-existent one-as-such and the non-existent many-as-such cannot be connected and transform into each other, since they do not exist. Whereas only plurality and unity existing in the system of being can move and transform into each other, which is a necessary consequence of materialist critique of Plato’s conception.

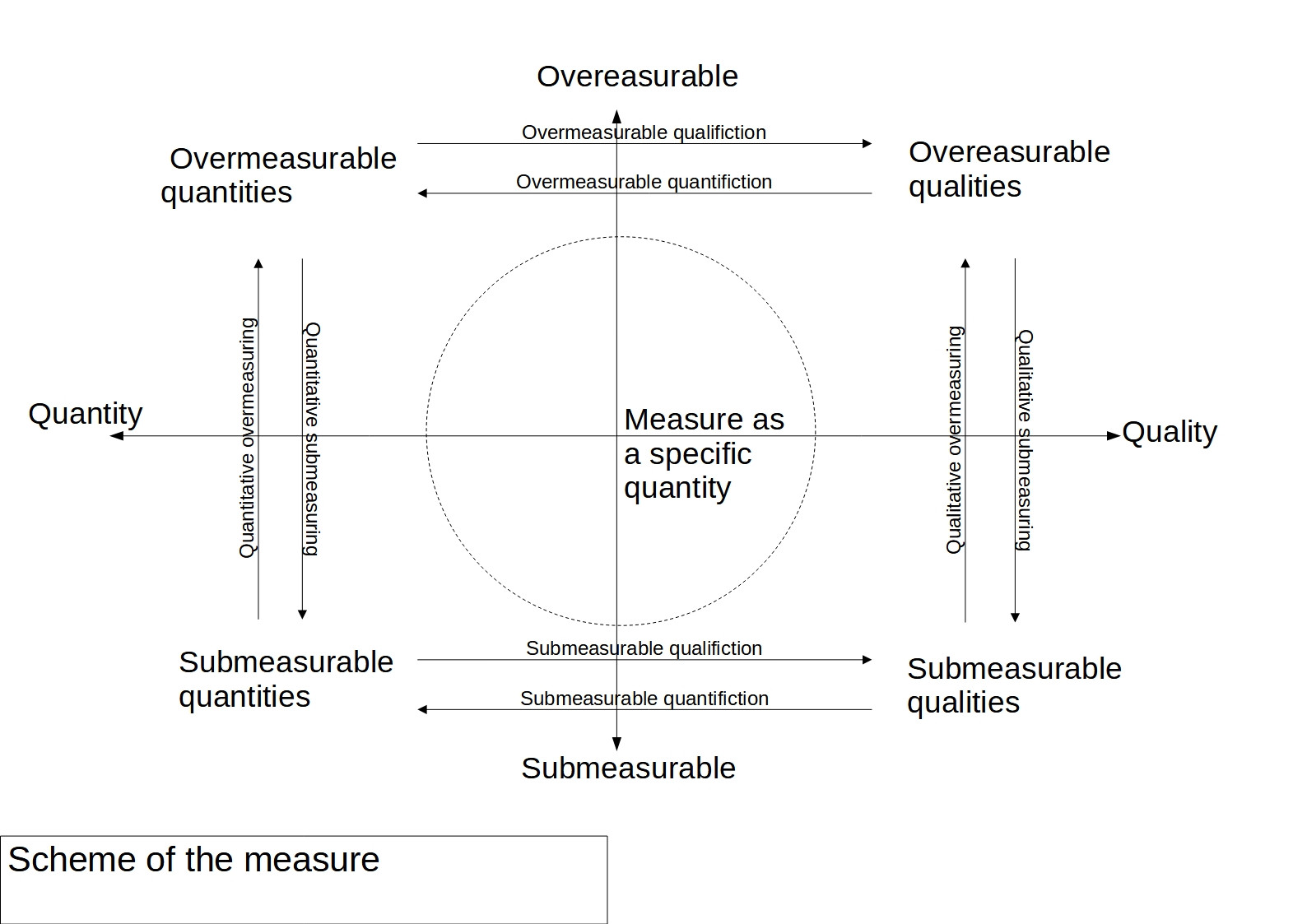

10. The scheme of a measure describes the dialectics of a measure as a specified quantity, that is, a quantity in which certain qualitative properties are revealed that arise and disappear when crossing a certain boundary, which is the measure. This problematic obviously refers to the second chapter of Hegel’s “Science of Logic,” whose impressive conceptual apparatus can and should be integrated into the system of modern materialist philosophy.

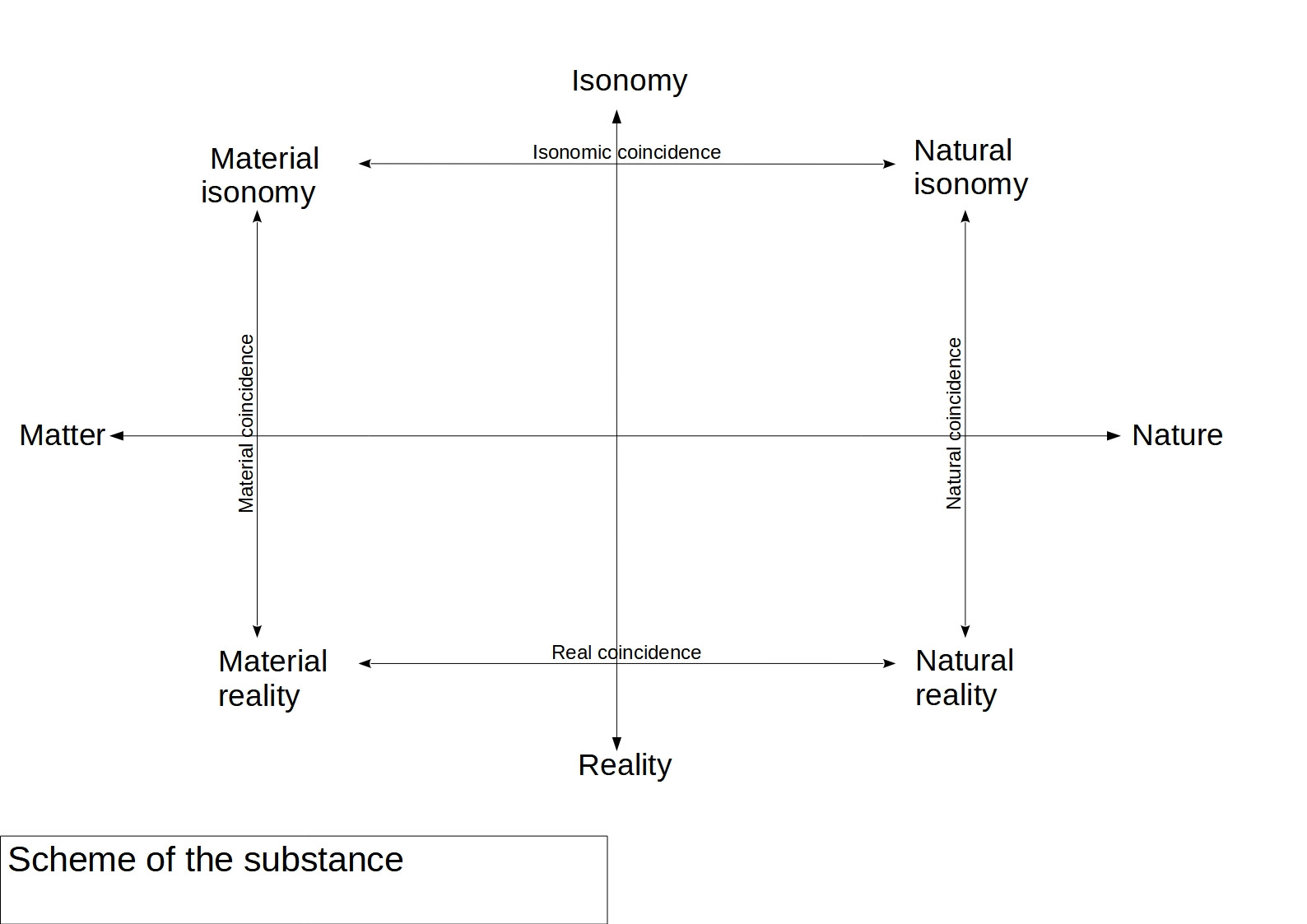

11. The scheme of substance describes the dialectic of the coincidence of the four aspects of substance:

Matter as an innumerable set of all possible objects, from infinitely small to infinitely large;

Nature as the eternal infinity of spaces;

Reality as a limitless set of codetermined spaces and particles;

Isonomy as the eternal and boundless reality of all possible.

It is obvious that in actual infinity these four logically distinct aspects of substance necessarily coincide.

By drawing the Z axis through the origin of coordinates to describe causes and effects, we will establish a Spinozist distinction between the productive nature and the produced nature — that is, between the productive forces of infinity, generating countless assemblages — and the assemblages themselves, to which these forces are inherent, so that in this case there are substantial opposites must match.

This scheme not only, in a sense, crowns the system of dialectical materialism, but is also important for the critique of religious obscurantism, whose supporters strive to present the cause of the world in the form of some kind of being separate from this world, and not as productive forces inherent in reality itself. By proving the coincidence of the productive nature and the produced nature as two aspects of one totality, we deal a mortal strike to any theology on the general ontological field and significantly facilitate our further critique of religious metaphysics and ideology.

It is significant that the schematic or figurative exposition of philosophy differs from the conceptual exposition proposed by Deleuze. If, according to Deleuze, every concept is a kind of unique unity, abstracted from all other concepts, then a figure is a way of stable connection of a whole group of concepts. Let’s count how many concepts the expansion scheme combines using the general assemblage scheme as an example.

Four directions of the axes: actual, virtual, possibilistic, realistic;

Four aspects at the intersection of axes: flows, phyla, universes, territories;

Eight simple transitions between aspects: real virtualization, real actualization, possibilistic virtualization, possibilistic actualization, actual realization, actual possibilization, virtual realization, virtual possibilization;

Eight counter-transitions between aspects: real devirtualization, real deactualization, possibilistic devirtualization, possibilistic deactualization, actual derealization, actual depossibilization, virtual derealization, virtual depossibilization;

Eight return transitions between aspects: real revirtualization, real reactualization, possibilistic revirtualization, possibilistic reactualization, actual rerealization, actual repossibilization, virtual rerealization, virtual repossibilization;

In summary: 32 concepts for one figure. Now imagine if we had to describe each of these concepts separately! With eleven figures we described 326 concepts: 32 for nine schemes, 26 for the scheme of being and 12 for the scheme of substance. These schemes can be extended by adding a third axis to describe cause-and-effect relationships, so that the number of concepts described will increase significantly.

Although Deleuze himself believed that philosophy should be limited only to the invention of new concepts, and that the figurative presentation of conceptual groups passes rather within the department of wisdom, in reality, living philosophy in its fluctuations cannot but embrace adjacent areas of wisdom and sophistry, as well as individual modes of application concepts — observation, reflection and communication. In fact, Deleuze in “What is Philosophy?” described an exclusive interpretation of philosophy, whereas I give an inclusive, expansive model of philosophizing, including the areas rejected by Deleuze and subordinating them to a uniform method.

Returning to schematization, one cannot help but note the fact that any method of schematization, no matter how productive it may be, has its limits. An assemblage scheme describes the ontology of concrete things taken in relation to statics. Whereas process ontology assumes a more complex description of assemblies that are in dynamic relationships. The dialectics of the process are significantly more diverse and do not fit into a uniform scheme. Therefore, in this case, it is more appropriate to talk not just about groups of schemes, but about lines of schematization. Let’s look at some of them.

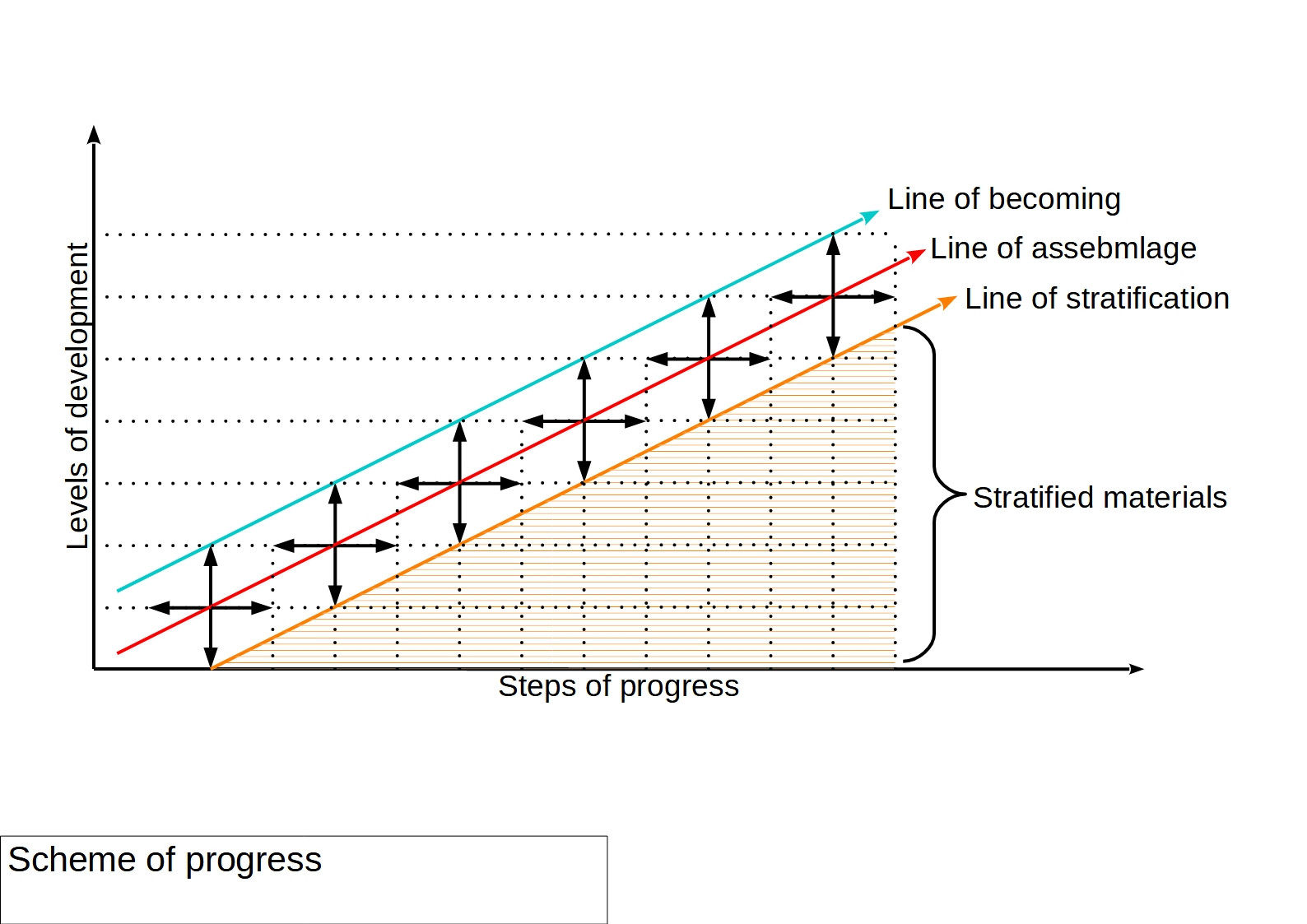

The line of schematization of progress includes five schemes reflecting the assemblage process.

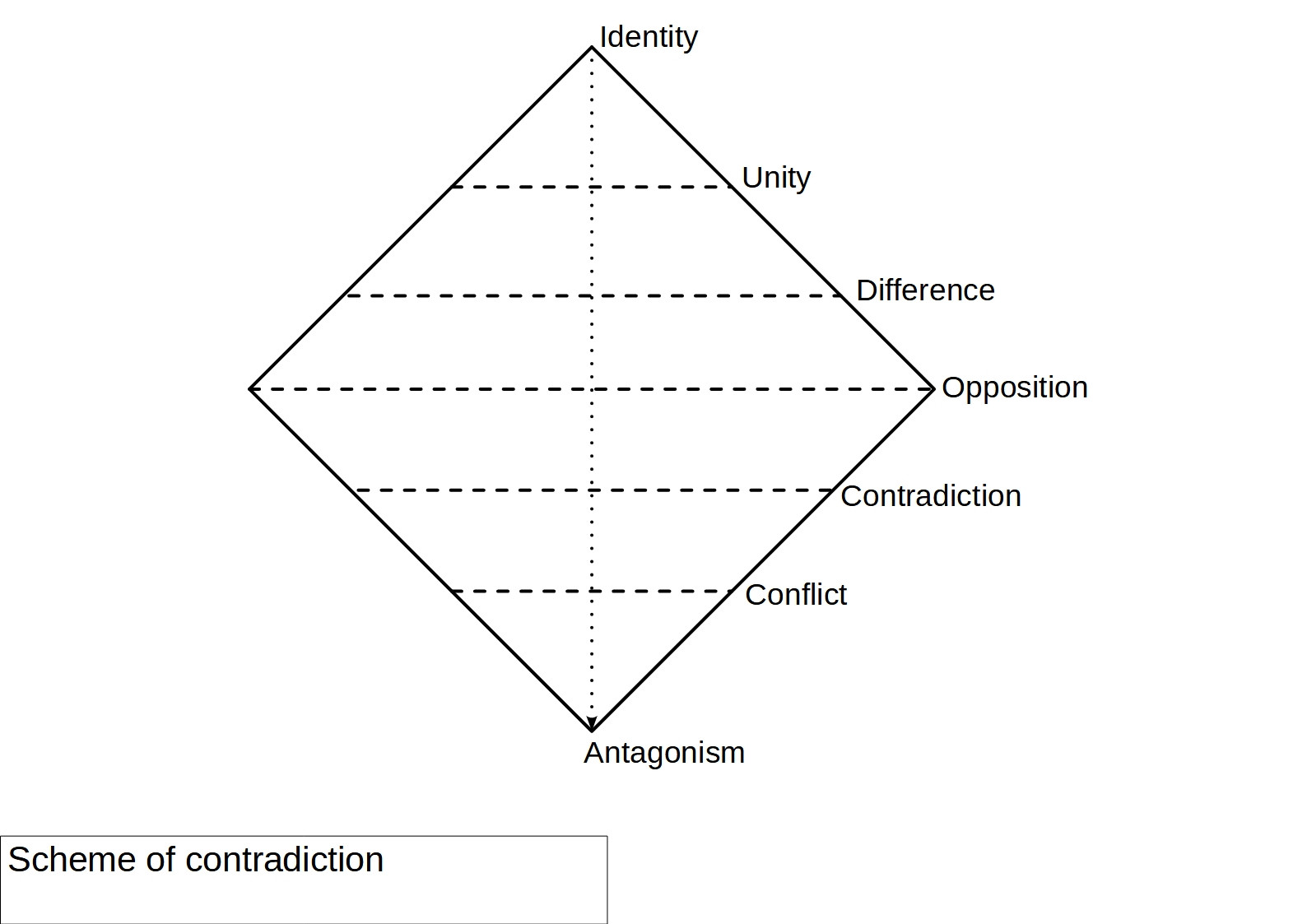

1. The scheme of contradiction is based on the conceptualization proposed by Tugarinov regarding the possible relations of opposites, ranging from identity as a complete coincidence, and ending with antagonism as a strictly mutual exclusion. The series identity-unity-difference-opposition-contradiction-conflict-antagonism allows us to avoid simplifying the actual complexity of the world and the relations of the modes that compose it. It adds 7 more concepts to the existing ones.

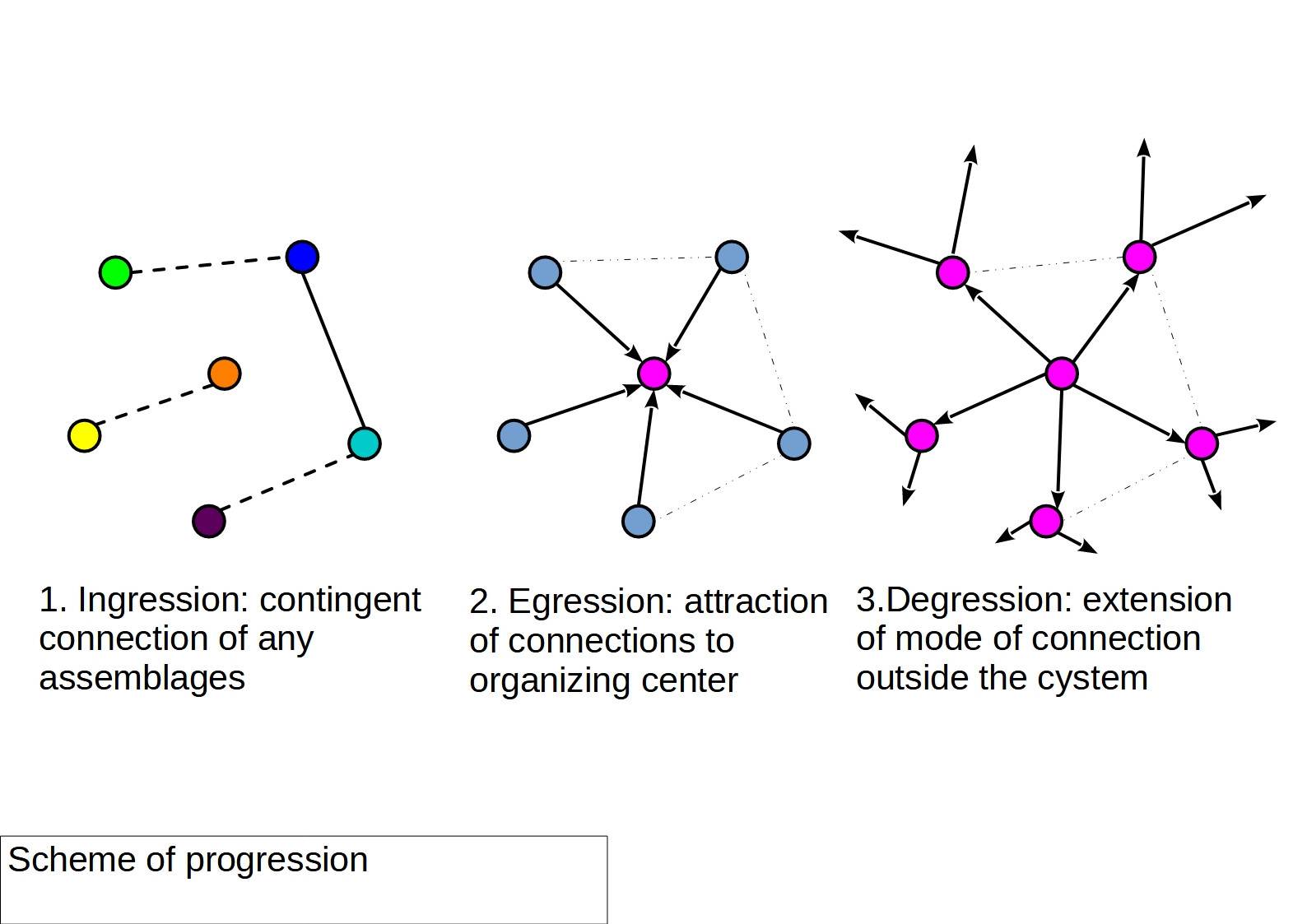

2. The scheme pf progression is based on the ideas of A. A. Bogdanov, put forward by him in “Tectology” treatise. In his opinion, in nature, any activity (in our understanding — modes or assemblages) can, in the process of development, first form contingent, separate connections, which is the meaning of the concept of ingression. Then, at the stage of egression, a center can be emerge in the network of interactions towards which these activities gravitate, in relation to which they form a system of subordinate relations. Finally, at the stage of degression, the formed center can become a source of new modes of assemblage, spreading throughout the entire system covered by egression and beyond its limits. It adds 3 more concepts to the existing ones.

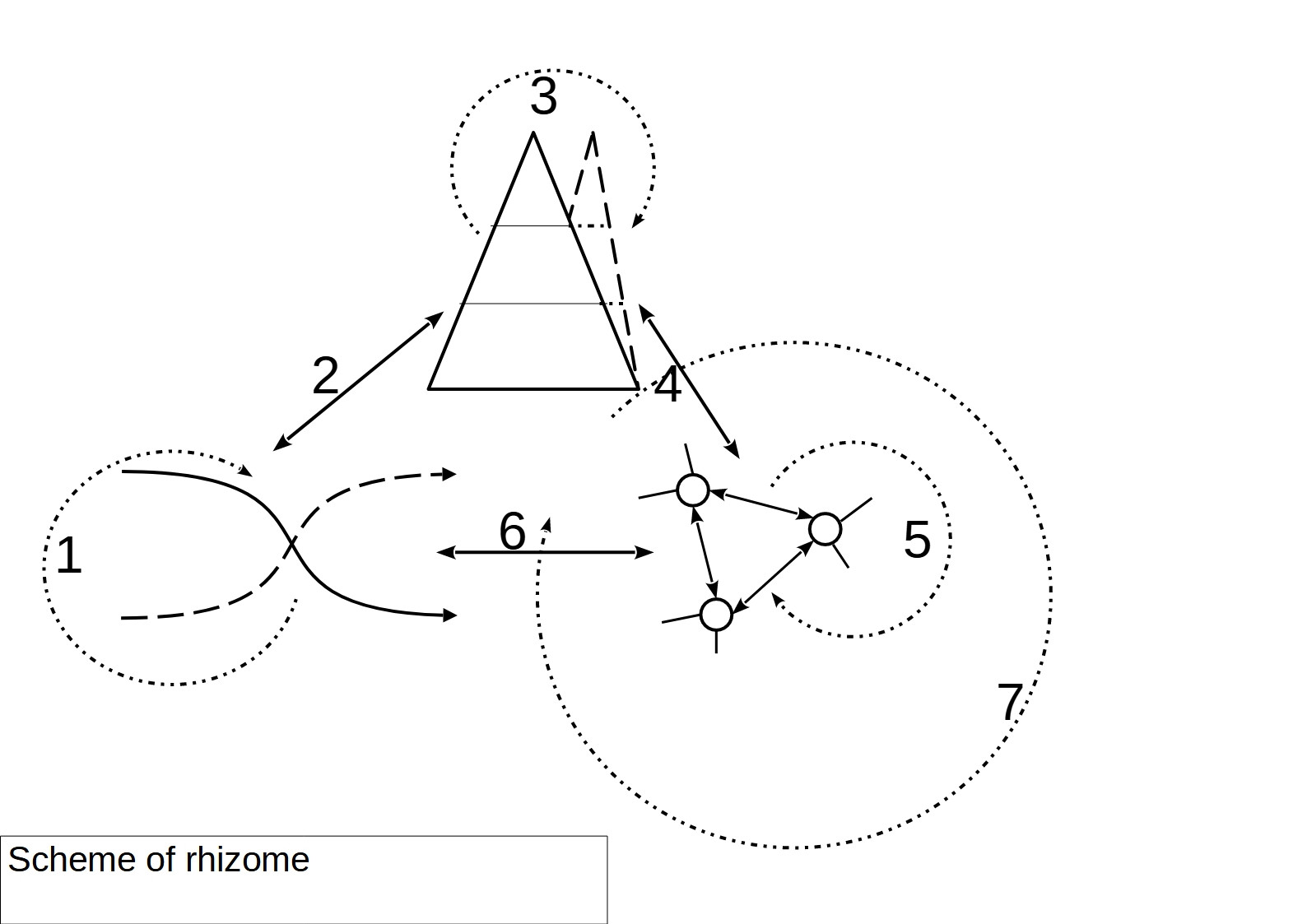

3. The scheme of rhizome as one of the main concepts of Deleuze and Guattari suggests, at the same time, a critique of popular ideas of interpretation of this concept. According to the vulgar interpretation, a rhizome is the same as a network of relationships, so there is no difference between rhizomatic and network structures. This idea comes from the fact that Deleuze and Guattari themselves developed the concept of the rhizome in the context of a critique of hierarchical and genetic ontologies. At the same time, in “Rhizome” they directly write that tree-like hierarchical systems always include elements of rhizomatics — and vice versa, every rhizome contains elements of tree-like structures, which is confirmed by specific historical analysis:

"There are knots of arborescence in rhizomes, and rhizomatic offshoots in roots. Moreover, there are despotic formations of immanence and channelization specific to rhizomes, just as there are anarchic deformations in the transcendent system of trees, aerial roots, and subterranean stems. The important point is that the root-tree and canal-rhizome are not two opposed models: the first operates as a transcendent model and tracing, even if it engenders its own escapes; the second operates as an immanent process that overturns the model and outlines a map, even if it constitutes its own hierarchies, even if it gives rise to a despotic channel." DG, Rhizome, transl. by B. Massumi

Thus, the vulgar Deleuzian identification of rhizome and network is erroneous. To correct this error, I schematized the rhizome as a set of genetic, hierarchical and network assemblies, as well as their internal and external contradictions, designated by numbers from one to seven. In this way, we achieve a more comprehensive and authentic reading of the concept of rhizome and greater correspondence with the reality described by it. She adds 11 more concepts to the existing ones: genealogy, hierarchy, network, rhizome, as well as 7 elementary contradictions.

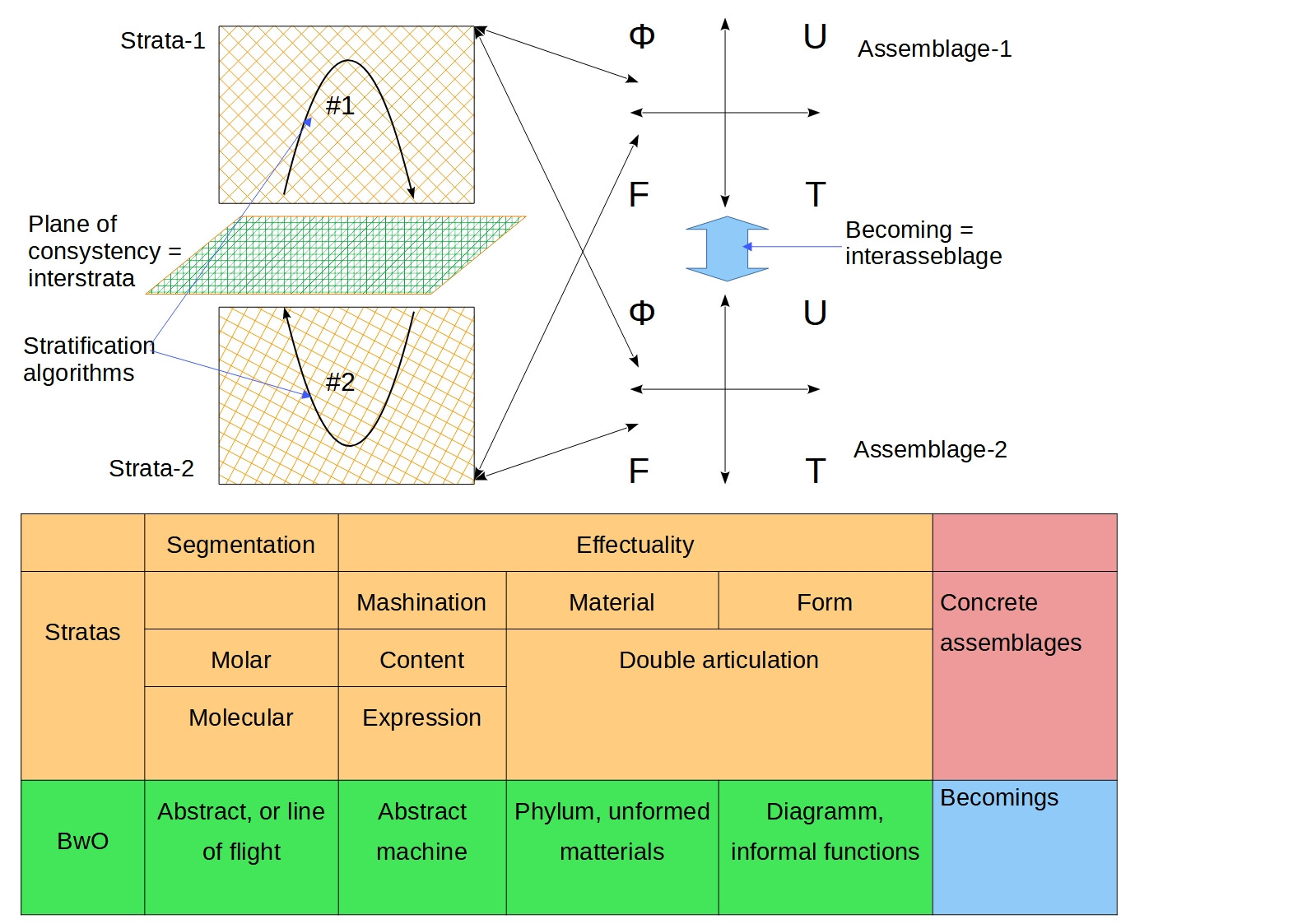

4. The scheme of becoming is a comprehensive scheme that clarifies the interconnection of a number of Deleuzo-Guattarian concepts:

Strata as assembled compositions of objects, spaces and the method of their connection/disconnection;

The plane of consistency as interstrata is a space of contact between two or more different strata, where various methods of connection/separation sublate each other, releasing the productive potential of destratified matter.

Assemblages as processes of connecting and disconnection of the objects and spaces, separately and in systems of interaction, about which we have already said enough;

Becoming as an interassemblage is a way of interaction between two or more different assemblages in which their algorithms are sublated in an emergent process.

Becoming is a very abstract category that allows us to describe processes in complex possibilized systems, biological or social. For example, a new interpretation of Marx’s “Capital”, in which economic processes would be described without humanistic ideologies, and on the basis of a universal materialist ontology, is a very promising area for using the concept of formation and a number of categories associated with it.

It adds 3 more concepts to the existing ones: strata, interstrata, becoming.

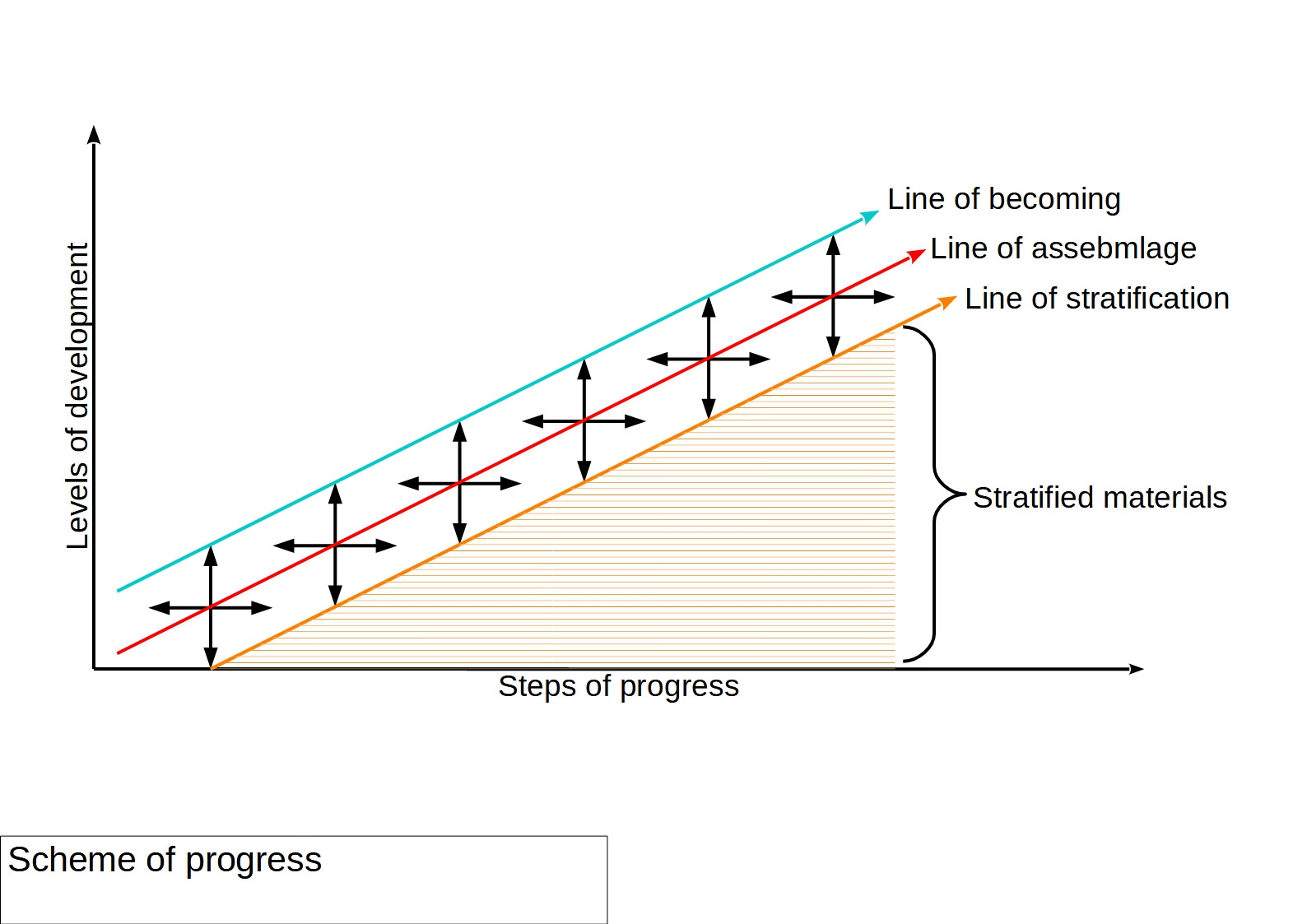

5. The scheme of progress is a processual simplification of the scheme of becoming, demonstrating the relations between the original scheme of the four aspects of assemblage, as well as three processes — stratification, assemblage itself and becoming during the development of matter. She adds one more concept to the existing ones: progress or development.

The progress line adds 7+3+11+3+1=25 concepts to the existing 326 concepts, in summary it will be 351 concepts.

The cinemafactory schematization line also includes five schemes reflecting the algorithms of the assemblage process.

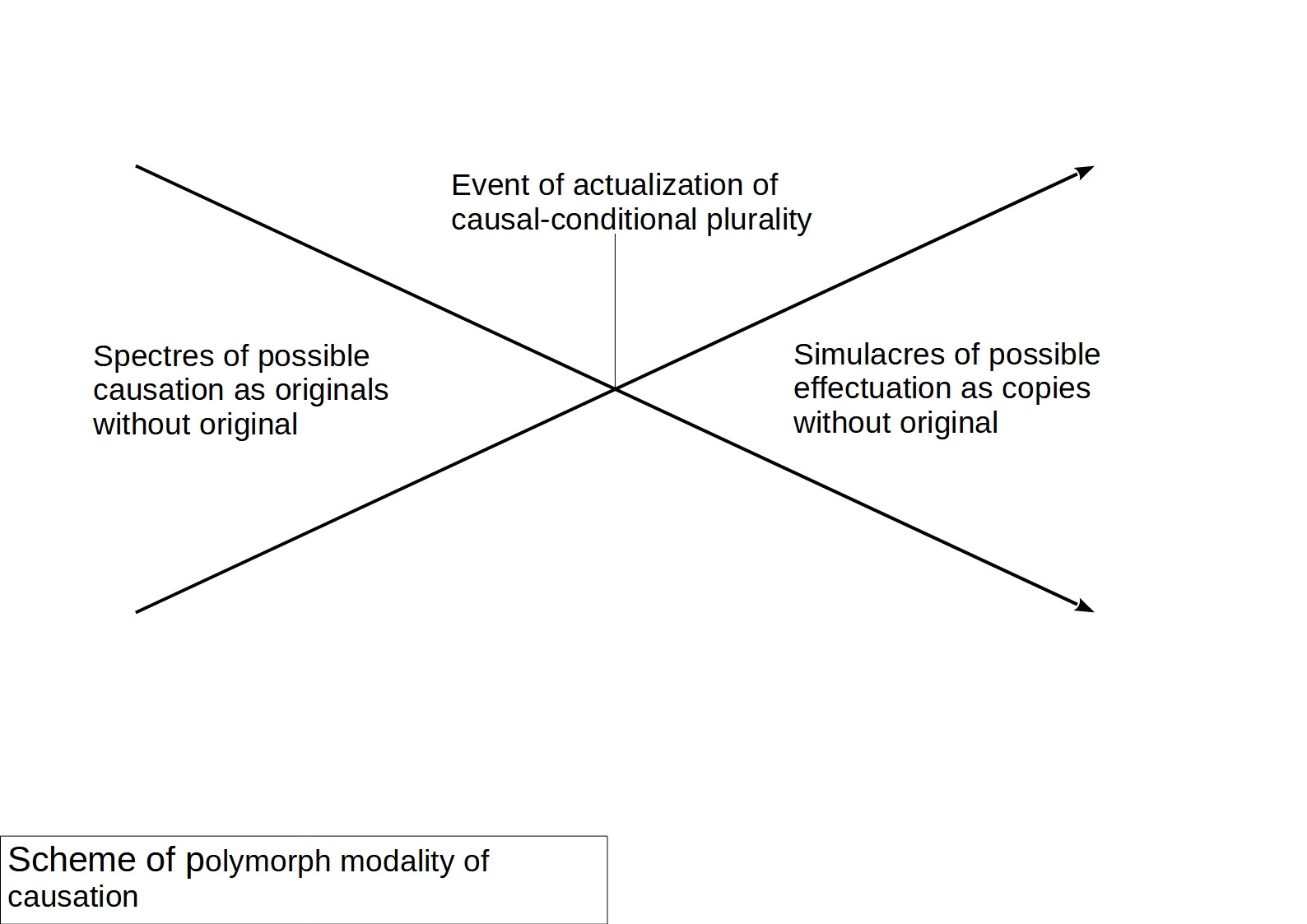

1. The scheme of polymorph modality is derived from the definition of material substance as isonomy. Indeed, if in the infinity of nature coexist all possible combinations of objects and spaces are comfortable, then any specific combination of them can and will be generated in all possible ways — and, on the contrary, different movements of the same composition of material elements will generate the entire spectrum of possible consequences. It adds 4 more concepts to the existing ones.

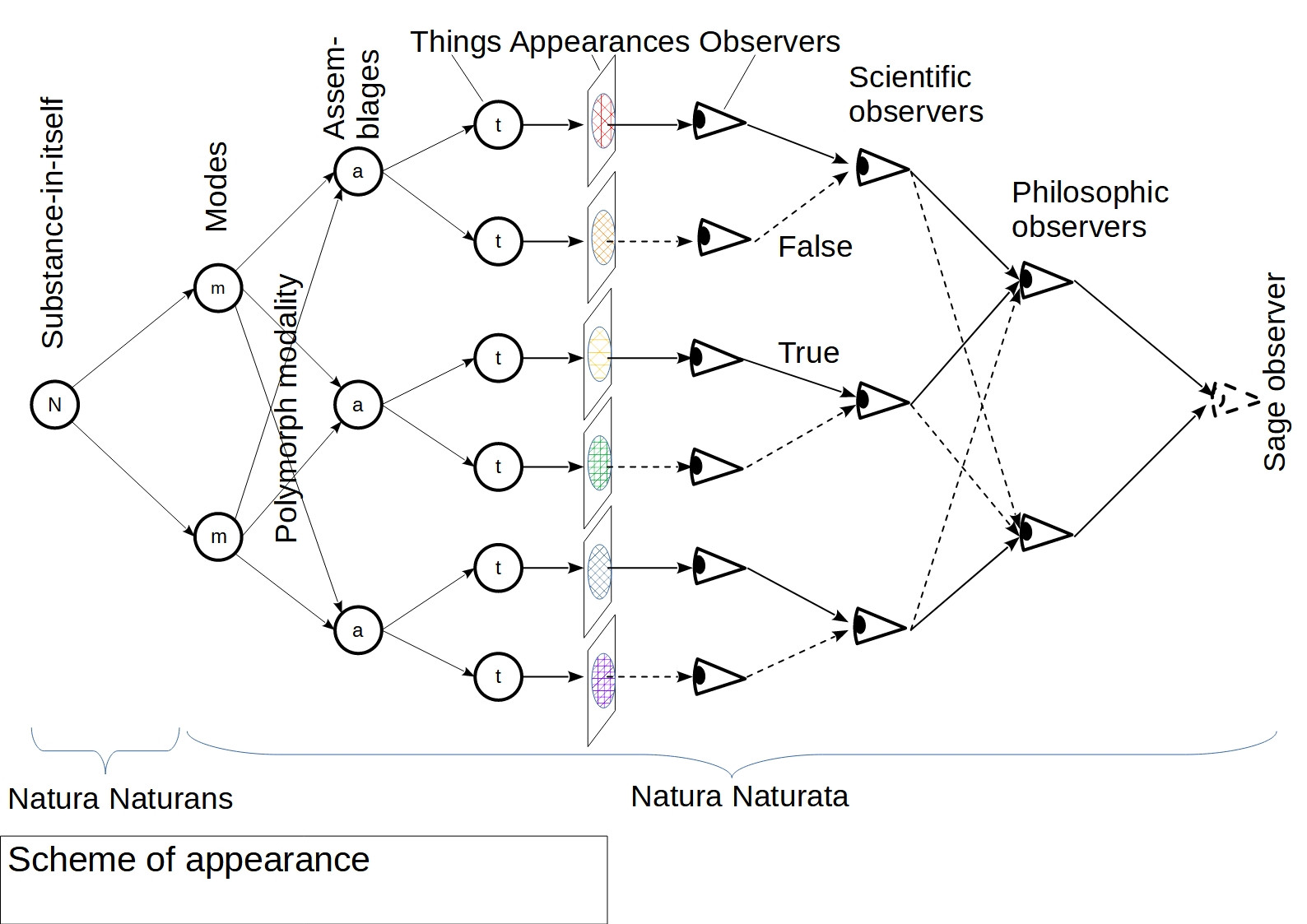

2. The scheme of appearance reveals the gnoseological consequences of the previous scheme, ascending from objects as the causes of cognition to their adequate and inadequate reflections as consequences. According to materialist ontology, the ultimate cause of all existing objects and their reflections is infinite nature, Natura Naturans, producing in countless modes an infinite number of assemblages, individual fragments of which (things) in contact with other objects are able to imprint their form on them, that constitues the being of appearances, while the objects to which this form passes are called observers. In principle, any object becomes an observer, whose motion after a collision with it reflects the shape of another object — atoms, molecules, planets, and so on. However, in this context, we are interested in the process of adequation, combining correct reflections of reality into more complete and accurate reflections — and excluding inaccurate, fuzzy reflections in which the elements of things and their relationships are deformed in one way or another. Therefore, by default, any social systems from which the process of generalization goes to scientific and philosophical observers are meant as observers. Moreover, although science presupposes an association of adequate reflections of the world, it still always contains a layer of errors due to the historical limitations of the means of observation. What errors can be eliminated during the transition from individual scientific disciplines to a holistic picture of the world compiled by philosophers — then we get a dialectical and materialistic worldview; or, on the contrary, accumulate — then we get idealistic and metaphysical philosophy.

It is essential that the universals comprehended by sciences and philosophy by generalizing individual observations, if they are carried out and collected correctly, reflect those universals that determine the existence of individual phenomena, logically and historically preceding them. Misunderstanding of this pattern in the history of philosophy was expressed in two metaphysical deviations: platonism, which postulates the pre-eternal existence of universals outside the things themselves and outside the material world — and nominalism, which postulates the existence of only individual things, and therefore undermines the possibility of scientific knowledge of the world. A recent example of nominalistic obscurantism is the concept of the recently deceased Bruno Latour, who believed, for example, that bacteria emerge on our planet not 4 billion years ago, but in the 18th century, thanks to the invention of Louis Pasteur.

The position of the sage, highlighted by a dotted line, denotes the potential, but never actual nature of the position in which all nature is known in all its infinity. As Pythagoras noted, only a god can be a sage who knows the absolute truth; a person can only be a philosopher, that is, a lover of wisdom. Since there is no God, the position of the sage remains empty, as a limit endlessly achieved by our efforts. We can, and therefore must, only endlessly approach the absolute completeness of knowledge, comprehending it to a greater and greater extent — which is the meaning of materialist philosophy and all science.

To the already existing ones, she adds 13 more concepts: producing nature, produced nature, 9 objects, as well as truth and error as an adequate and inadequate reflection.

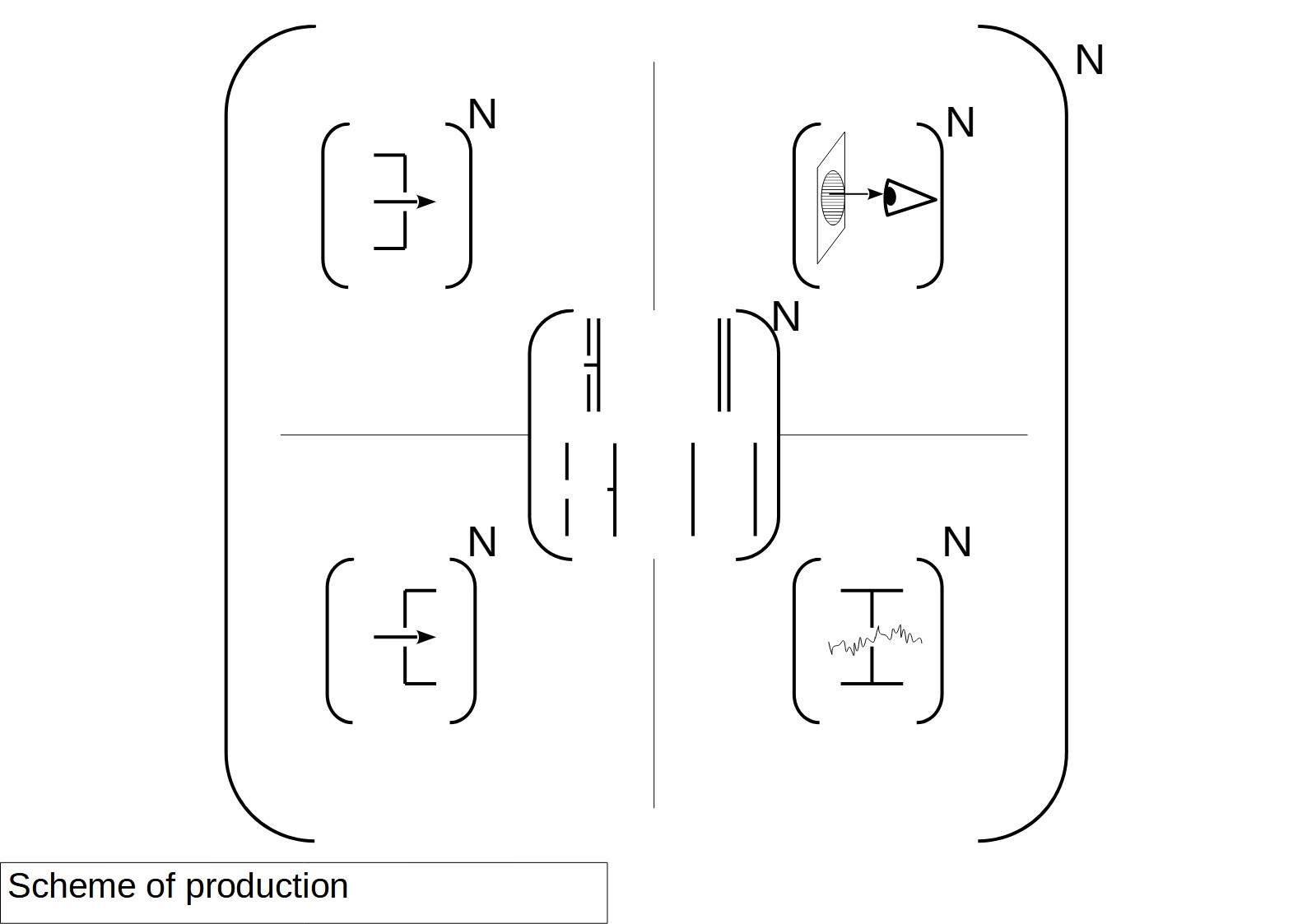

3. The scheme of production clarifies the meaning of the Deleuzo-Guattarian concept of desiring machines, like many other concepts of these authors, usually interpreted vulgarly as any interactive gadgets. In fact, the concept of desiring machines was derived by Guattari through a critique of Lacanian psychoanalysis, from the concept of partial drives discovered by Freud in his study of the stages of psychosexual development. According to Freud, desire as psychic energy is concentrated in those areas of the body that interact most intensively with the outside world at one or another stage of the body’s development. Thus, the mental life of a baby sucking a breast or a bottle of milk is concentrated around the process of sucking and the mouth as a bodily opening through which this process is carried out. The same is true for the subsequent stages — anal, phallic, latent, genital, discovered by Freud — as well as scopic and vocal, discovered by Lacan. However, in the approach of Freud and Lacan there is biologization and anthropocentrism, explained from their own theory by under-treated Oedipalization, in which the subject’s attention and desire is fixed on an artificially isolated fragment of reality from a countless number of possible ones — a separate biological organism. If we, as scientists, discard this product random fixation, then the division of ways of interaction between systems should not be anthropocentric, but universal, equally describing the interactions of molecules, populations, states, languages or galaxies. Guattari and Deleuze’s schizoanalysis represents a step in this direction. However, due to the deviation into the metaphysics of the individual, their project collapses halfway. A more materialistic interpretation of the work of desiring production can be extracted from the works of our contemporary Yoel Regev, according to whom the elementary ways of connecting objects and spaces are maximal contiguity and minimal penetration, biologically given in sexual practice, but not reducible to the latter, ensuring the emergence and redistribution of other machines, cutting off flows. It adds 6 more concepts to the existing ones.

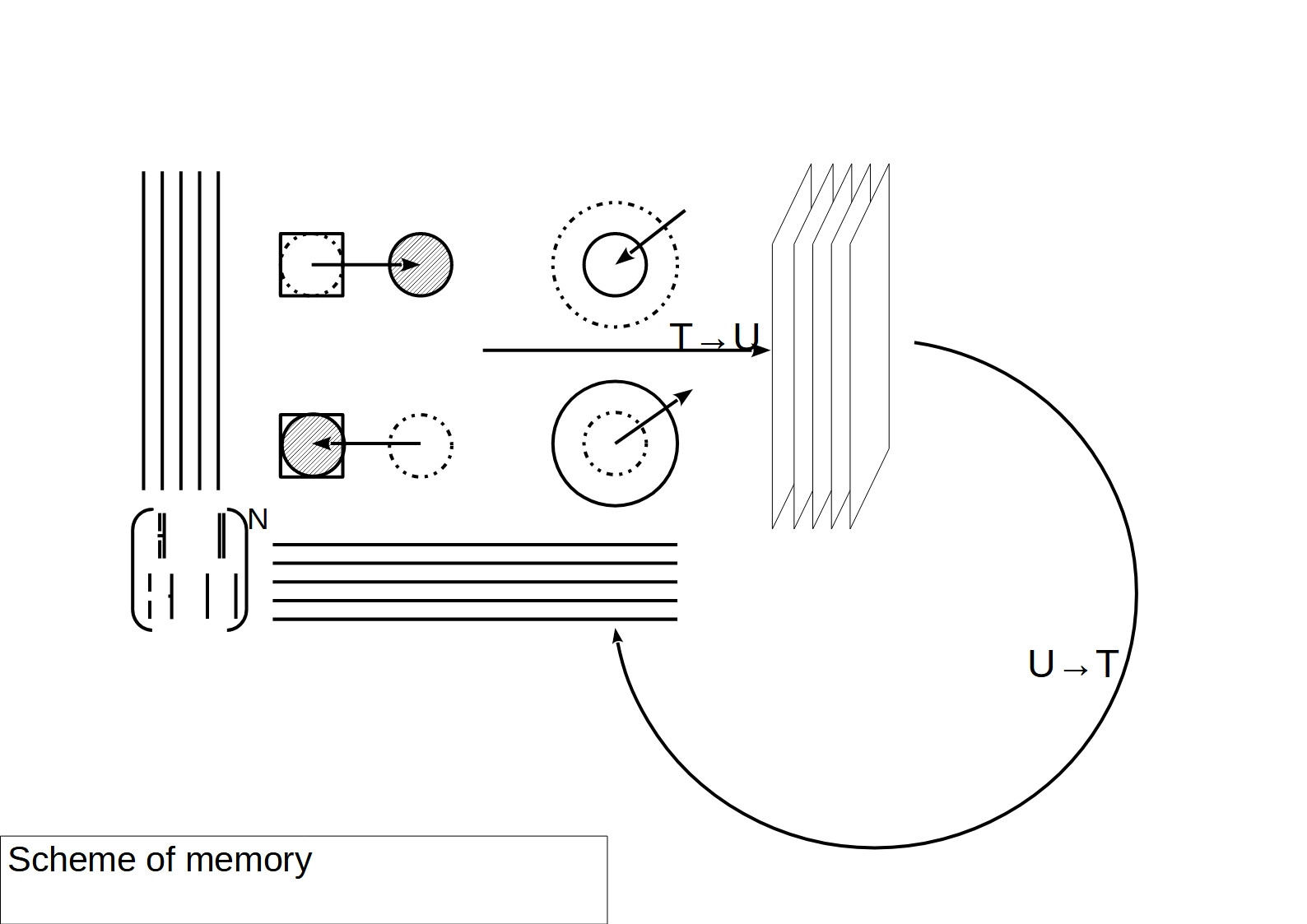

4. The scheme of memory clarifies the meaning of the Deleuze-Guattarian concept of the body without organs as a virtual surface from which desiring machines arise, along which they are distributed and into which they are deconstructed. The surface itself has the properties of stretching and compression, both spatial and semantic, forming a metaphorical or paradigmatic axis of selection; whereas objects in relation to the surface have the properties of displacement and compatibility, forming a metonymic or syntagmatic axis of combination. A machine consisting of combinatorial and selective components is capable of selecting and synthesizing sections of objective and subjective strata as aspects of a single anamnetic duration, the disintegration of which constitutes a new objectivity, while the same apparatus of maximal contiguity and minimal penetration lies at the basis of the connectivity of the processes of virtual connection and separation. It adds 7 more concepts to the existing ones: displacement-combination, condensation-dispersion, subjectivity, objectivity and duration as their continuous unity.

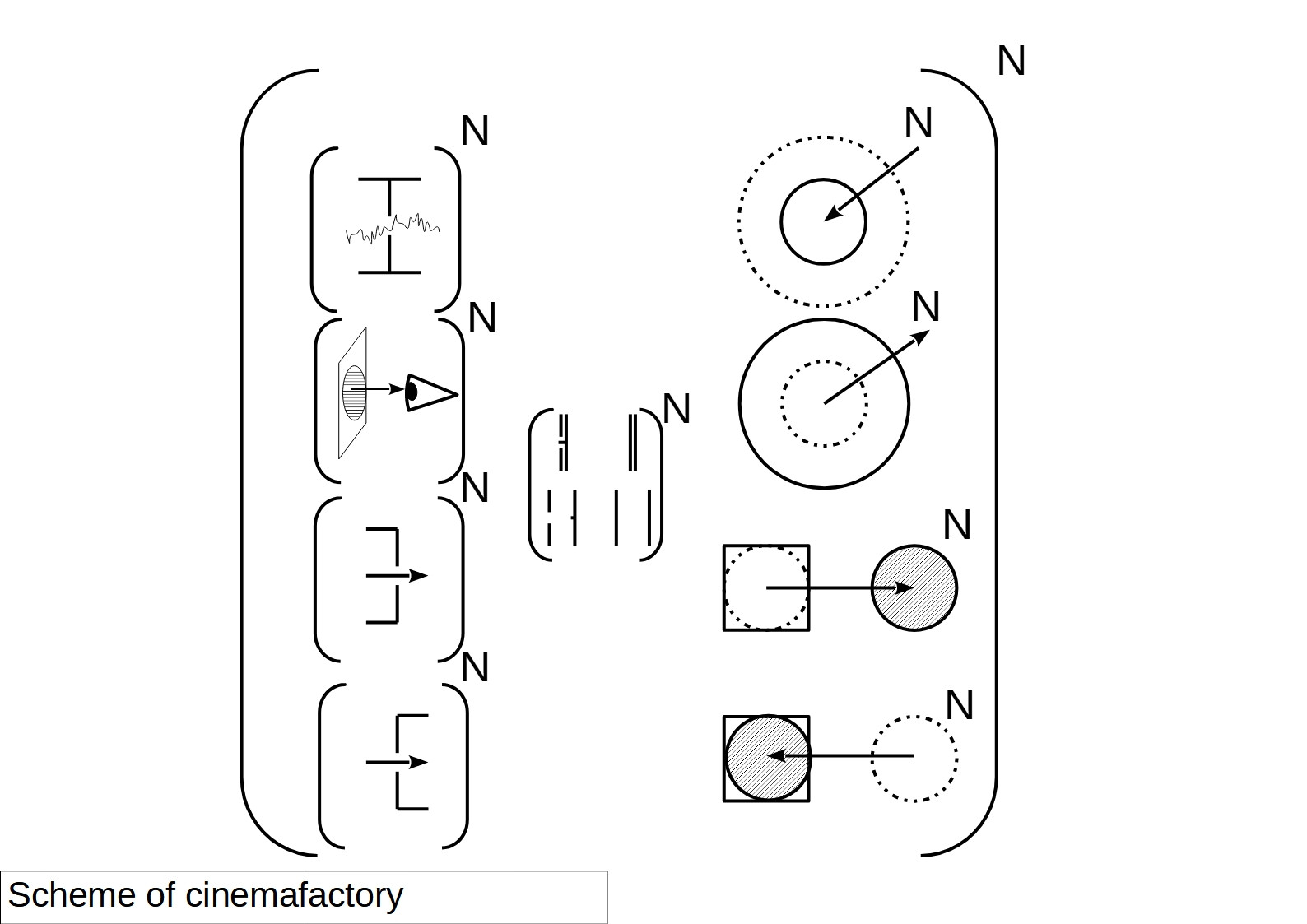

5. The scheme of the cinemafactory clarifies the general meaning of Deleuzo-Guattarian philosophy, combining the actual and virtual dimensions of the assemblage process and referring to the concept of the cinemafactory world formulated by me in the article “Beyond the Threshold of Humanity” — a deserted process of mutual production of real and effectual machines, which sublates the humanistic understanding of the world as a world of human activity. The coincidental apparatus of maximal contiguity and minimal penetration, common to actual and virtual processuality, combines both aspects, generalizing the way they interact. It adds one more concept to the existing ones: the film factory itself.

The cinemafactory line adds 4+13+6+7+1=31 to the existing 351 concepts, for a total of 382 concepts.

It is clear that further development of this basic set of concepts by applying them to oneself, to areas of applied philosophy and to methodological reflection on the entire process will allow it to be speculatively multiplied many times over. And here we are faced with the question: how can the growing philosophical encyclopedia be written down? In the article “Concept of assemblage” (RU) a three-part description is introduced for the basic concept of contemporary materialism, which is applicable to all derived concepts:

1. Definition — the internal meaning of a concept, resulting from the meaning of its component parts.

2. Meaning — the external meaning of a concept, resulting from its place in relation to other concepts, considered in three ways: genealogically, hierarchically and in a network manner.

3. Usage — the way of applying this concept in philosophy, science, politics, art and other fields of activity.

In a similar way, more complex philosophical objects can be considered: books, philosophers, philosophical schools and tendencies of thought: what they represent in themselves, what they are in relation to similar objects, and what benefit they can bring to us.

Thus, the rational grain extracted from the history of philosophy — a simple and correct ontological assemblage scheme, turns out to be an extremely productive tool that allows you to reassemble all historical and philosophical material, organize a conveyor selection of rational grains.

3. Critique of metaphysics and ideology

A distinctive feature of materialist philosophy is its critical orientation, due to the fact that philosophers, as constructors and deconstructors of meaning systems, living in society, are forced to directly or indirectly serve two opposing trends: the preservation and destruction of the current state of affairs. And since many other social classes are also interested in these processes in one way or another, due to the coincidence or opposition of interests, philosophers find their audience in these interest groups, and those in philosophers find exponents of their will.

In accordance with two main trends in the change of society, revolutionary and reactionary. And since society is a developing system, the revolutionary tendency to create new things and destroy old, obsolete existence is predominantly true, while the reactionary tendency to suppress the new and preserve the old is predominantly false, preventing the growth and development of society. This does not mean that revolutionary ideas and actions do not contain errors, or that conservatives are not occasionally right. But the essence of the matter is that the progressive understanding of social reality reflects the ability of society to enrich itself in every sense of the word, productively consuming the various benefits of Nature — while the reactionary understanding of society is based on the refusal of consumption or its limitation, leading to poverty, hunger and death in all meanings of this word.

Since the existence and enrichment of certain groups of society — the parasitic, exploiting classes — is associated with the impoverishment of all other members of society — the general division of philosophers into materialists and metaphysicians, into progressive and reactionary, is specified for each historical formation. Philosophers who justify the domination of slave owners — or slave uprisings, the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie — or proletarian revolutions: the initial principle of division is extremely simple and univocal, although it is sometimes clouded by complex historical circumstances.

All this is of the utmost methodological importance for understanding the aim of contemporary materialist philosophy and methods of achieving it. If the goal of materialist philosophers is to participate in the enrichment of the entire society, in accelerating scientific, technological and social-democratic progress, then an obvious task follows: to criticize those ideas that give a false presentation of the structure of the world, as well as to explore the natural movement of social matter, promoting their formation and destruction. Methodologically, this task is divided into the following stages:

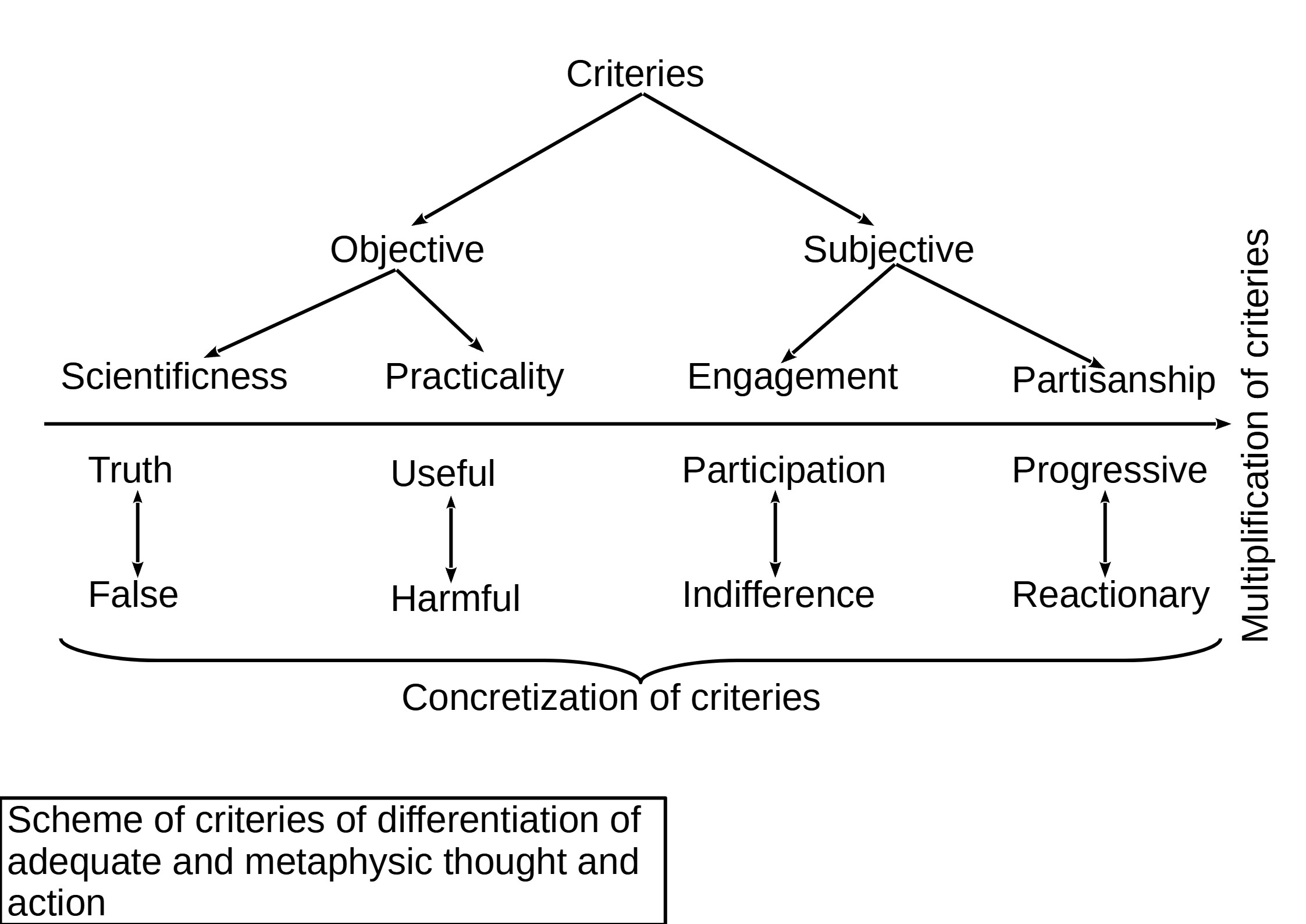

1. Critique of metaphysics. I write in more detail about the critique of metaphysics as an inadequate philosophy in the articles “Criteria of Metaphysics” and “On Metaphysics and Ideology.” The task of both articles was to form a more complex, in the limit — all-encompassing understanding of the nature of metaphysics as an inadequate philosophy. The result of conceptualization was three schemes that consistently reveal the methodological and ontological meaning of metaphysical distortions.

This scheme reveals the methodological meaning of metaphysics as a philosophy that deviates from the scientific knowing of truth into the propaganda of anti-scientific delusions; from the search for practical benefits into useless and harmful pseudo-practices; from passionate engagement into the global struggle for a better future to passive, contemplative detachment; from practical and conscious unification together cothinkers in the struggle for communism as a concrete ideal of this future into meaningless resistance to inevitable change. The list of methodological criteries for distinguishing between adequate and metaphysical philosophy can and should be extended; however, these four criteries already provide a basic understanding of methodological adequacy as a combination of an objective study of the actual movement of society — and subjective changes in society in accordance with objective knowledge. This idea of connecting the objective and the subjective is also the definition of Orthodox Marxism according to the article of the same name by D. Lukács. On the contrary, metaphysical philosophy is defined negatively, as that which falls outside this bundle, as wandering in the darkness of abstractions and pseudo-practices — as that which we must struggle and that we will defeat.

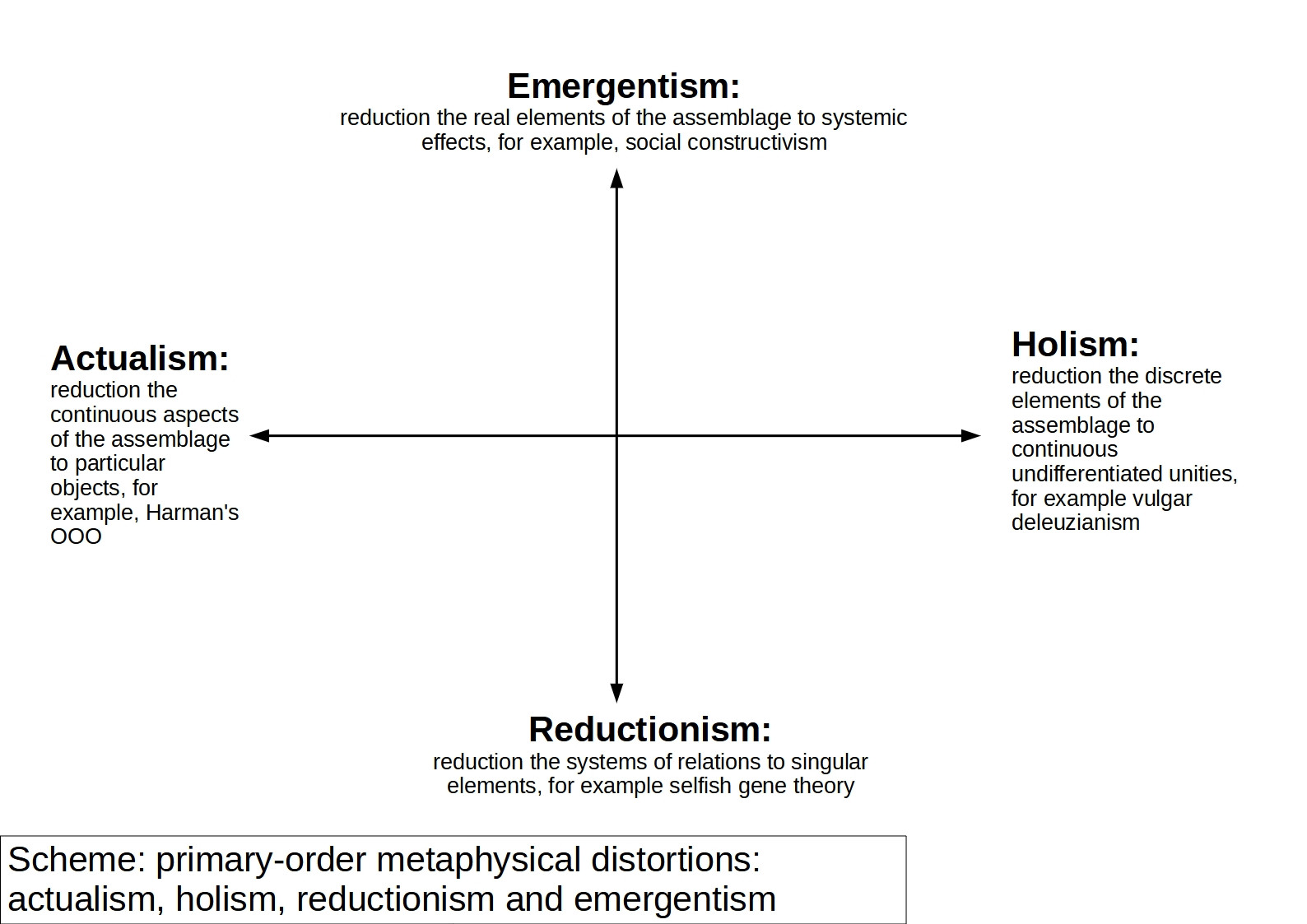

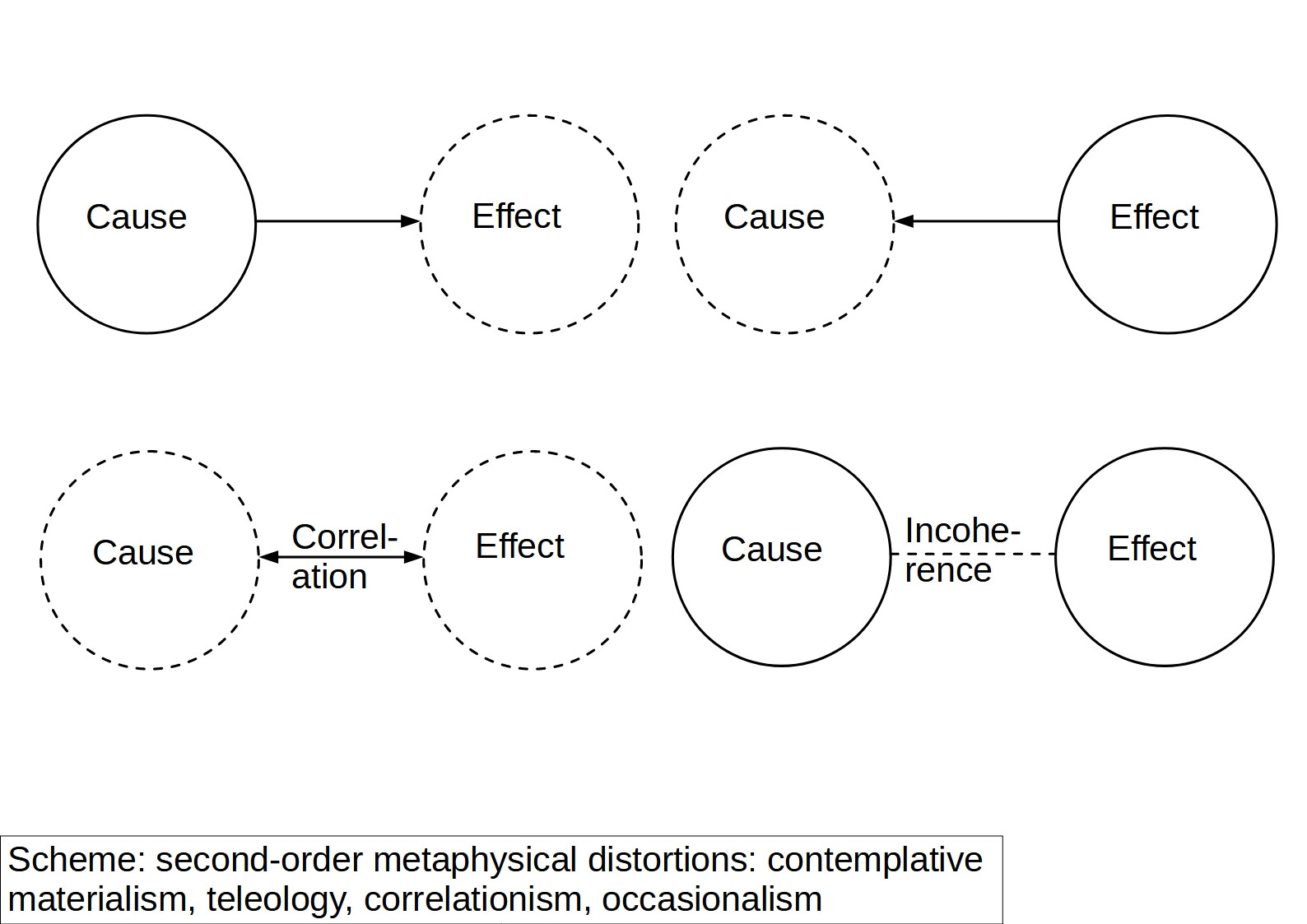

In contrast to the methodological scheme of metaphysics, this and the following schemes demonstrate the ontological meaning of metaphysical distortions, outlined by the figure of the assemblage as a unit of reality. In fact, if reality consists of assemblages, then metaphysics as a distortion of the actual state of affairs can only be one or another distortion of the relation between aspects of the assemblage: an overestimation of some, an underestimation or a complete denial of other aspects. Accordingly, reductionism is synchronically distinguished as the reduction of systems of relations to single elements; emergentism as the reduction of real elements of an assemblage to systemic effects; actualism as the reduction of the spatial and continuous aspects of an assemblage to spaceless sets of parts; holism as the reduction of discrete parts into seamless wholes.

We can further identify four diachronic distortions of the assemblage, which misinterpret the relationship between cause and effect. Contemplative materialism assumes that causes completely determine effects, from which a passive, apolitical position is derived. This does not take into account the fact that the activity of subjects is one of the ways of manifestation of the causal activity of matter, and consequences are capable of transforming the way causality functions at the next stages of development. Teleology, on the contrary, assumes that effects can somehow miraculously predetermine causes and themselves, acting on the past from the future. This idea is more erroneous than contemplative materialism, and underlies idealistic teachings about gods and spirits who supposedly created the world, and now they are sending miracles and signs to believers about future events. Correlationism is a metaphysics that seeks to avoid the extremes of the previous two, but as a result combines the shortcomings of both. According to the correlationist worldview described by Q. Meillassoux, between subject and object, between cause and effect, there is a certain “principal coordination”, so that one does not exist without the other, and both opposites are only poles of the connection between one and the other. Finally, occasionalism is the idea that causes and effects are separated from each other by a stone wall, and the relationship between them is unthinkable. Since such a position contradicts observable facts, its supporters are forced to introduce additional supports into their systems in the form of God in Malebranche or transcendental categories of pure reason in Kant, which would somehow still give the appearance of coordinating causes and effects with each other.

More detailed critique of these metaphysical distortions and their combinations is the subject of separate articles. What is important to note now is that in comparison with classical Marxism, in which metaphysics was interpreted exclusively as reductionism, or rather as a reductionist-particularist unity. In “The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science” Engels describes the metaphysical way of representing reality, characteristic of natural science of the 16th-18th centuries, as follows:

"<…> observing natural objects and processes in isolation, apart from their connection with the vast whole; of observing them in repose, not in motion; as constraints, not as essentially variables; in their death, not in their life <…> metaphysical mode of thought. <…> To the metaphysician, things and their mental reflexes, ideas, are isolated, are to be considered one after the other and apart from each other, are objects of investigation fixed, rigid, given once for all."

Our conceptualization allows us to analyze already at this stage metaphysical teachings with eight times more powerful resolution, identifying instead of just one, eight elementary metaphysical biases in the field of ontology.

As a next step, we can outline the disagreement between dialectical-materialist or adequate philosophy — and the seven metaphysics that oppose it: objective, subjective and intersubjective idealism, as well as mechanistic, dogmatic and eclectic materialism together eclecticism as mixture of all counted. In contrast to the classifications listed above, which describe the general patterns of metaphysical trains of thought, our list describes specific metaphysical directions under which certain specific metaphysics and metaphysical schools of philosophy fall.

An essential point is the fact that these schemes, essentially accurately capturing some properties of inadequate philosophy, need to be supplemented and specified using historical and philosophical material. Only by studying the discoveries and misconceptions of specific philosophers, philosophizing ideologists and scientists, it is possible to improve the methods of critique, achieving as exhaustive as possible in the cataloging and classification of possible errors, the reasons for their occurrence, avoidance and elimination.

2. Critique of ideologies. A number of articles were devoted to critique of ideologies as forms of false consciousness (Experience of faith and unbelief (RU); From religion to atheism — reading list (RU); Essence of ideology (RU); History of ideology (RU); To understanding ideology — reading list (RU); Ideology, or on belief in humans, gods and ghosts (RU)), which contain some tables and schemes that clarify the essence of this matter.

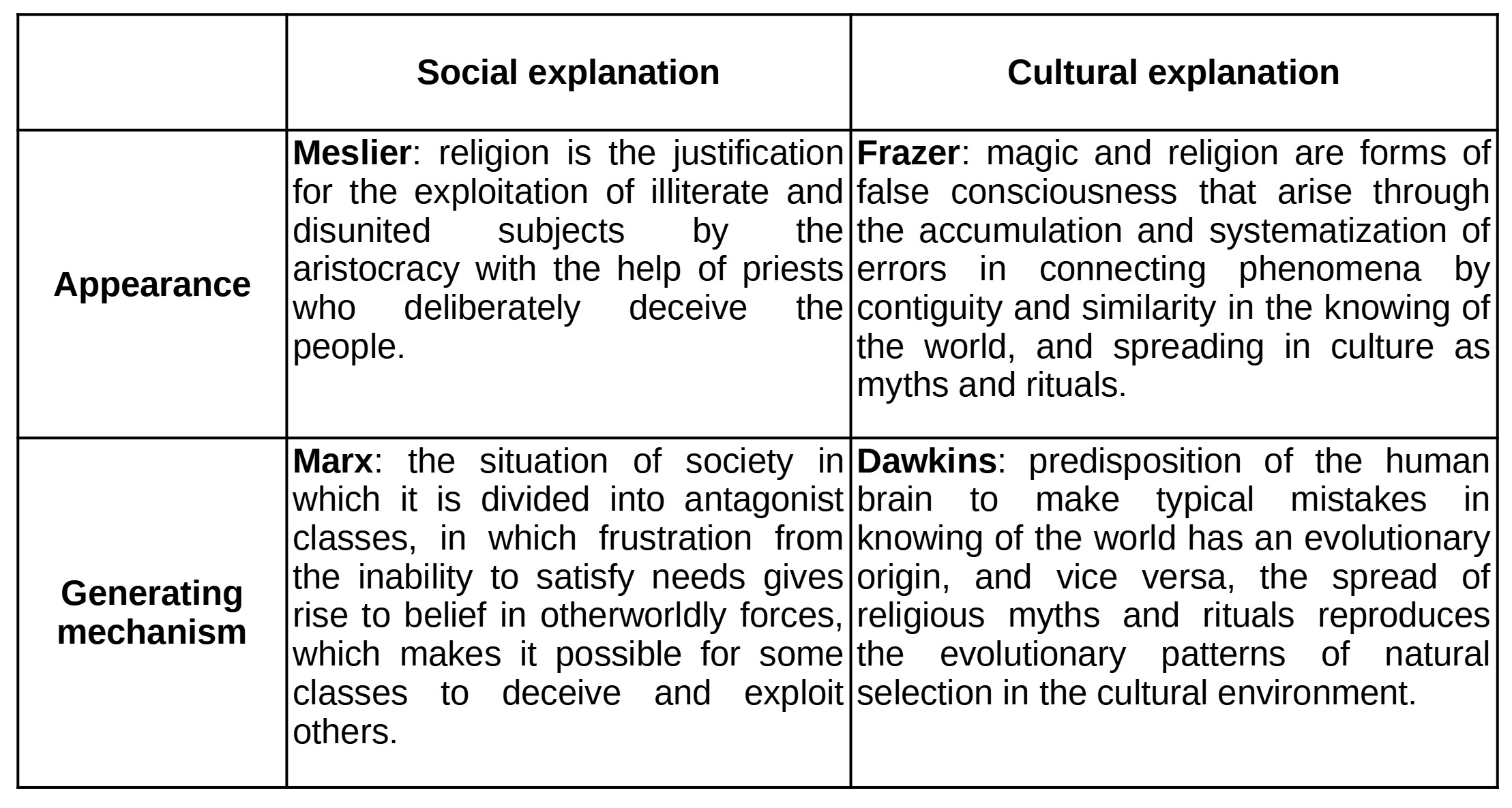

Let’s start with a table of four factors of ideology.

This table records four factors that form the ideological attitude and worldview: social and cultural generative mechanisms, as well as social and cultural systems of relations already produced by previous steps of the generative mechanisms. The concepts of Karl Marx and Jean Meslier, as well as James Fraser and Richard Dawkins, describe different aspects of the same process of the generation and functioning of false consciousness.

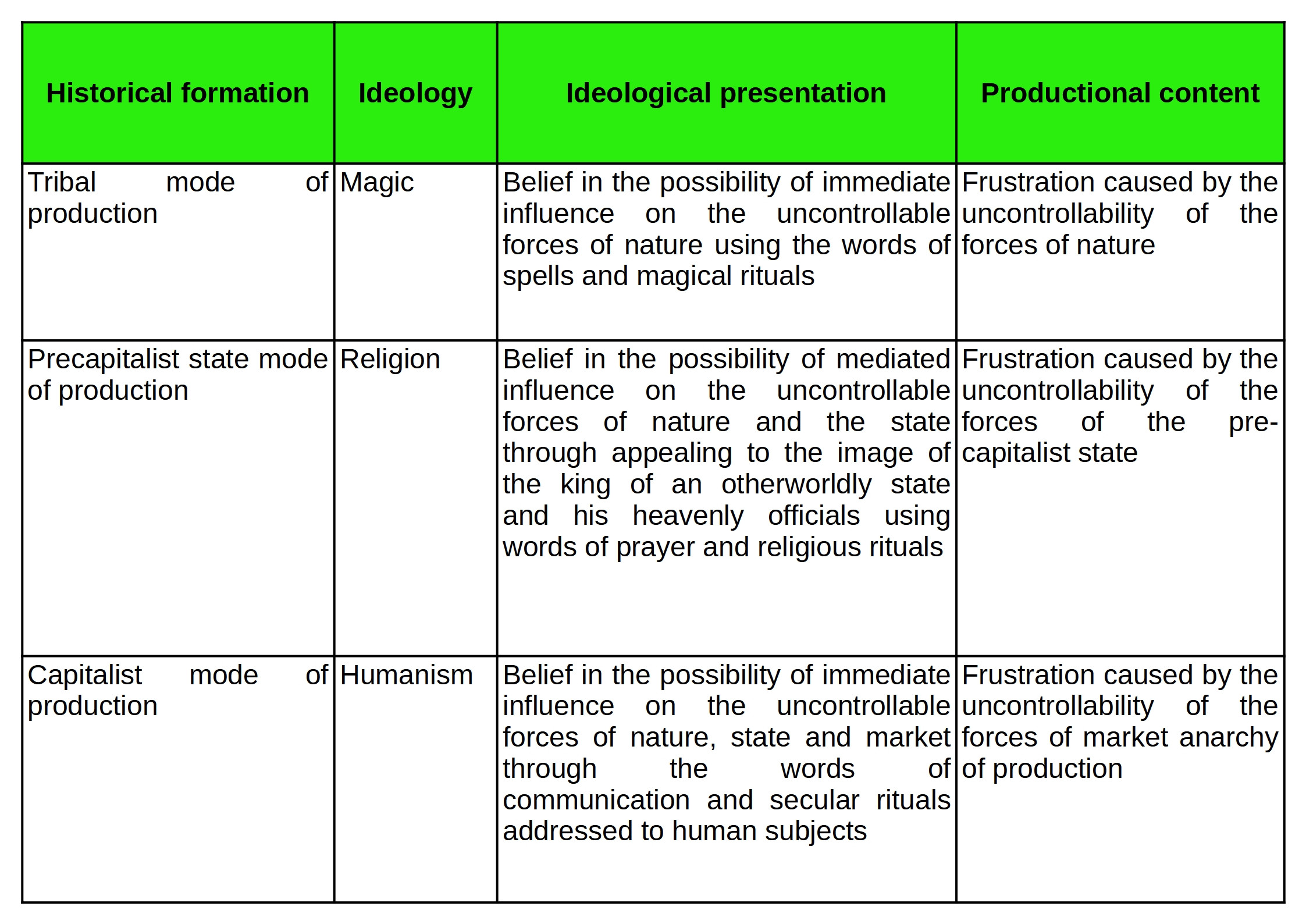

The following table shows the development of elementary forms of false consciousness in history, relating them to economic formations. Thus, magical prejudices ideologically express the insoluble contradictions of the tribal order; religious belief in gods and worship of them are express contradictions of pre-capitalist statehood; the humanistic belief in “concrete humans” expresses the contradictions of capitalism, the overdetermining work of the ideological apparatuses of the bourgeois state. The three basic forms of personalization of impersonal social assemblages form a general range of ideological formations, the specific variations of which are infinitely varied and require more detailed study.

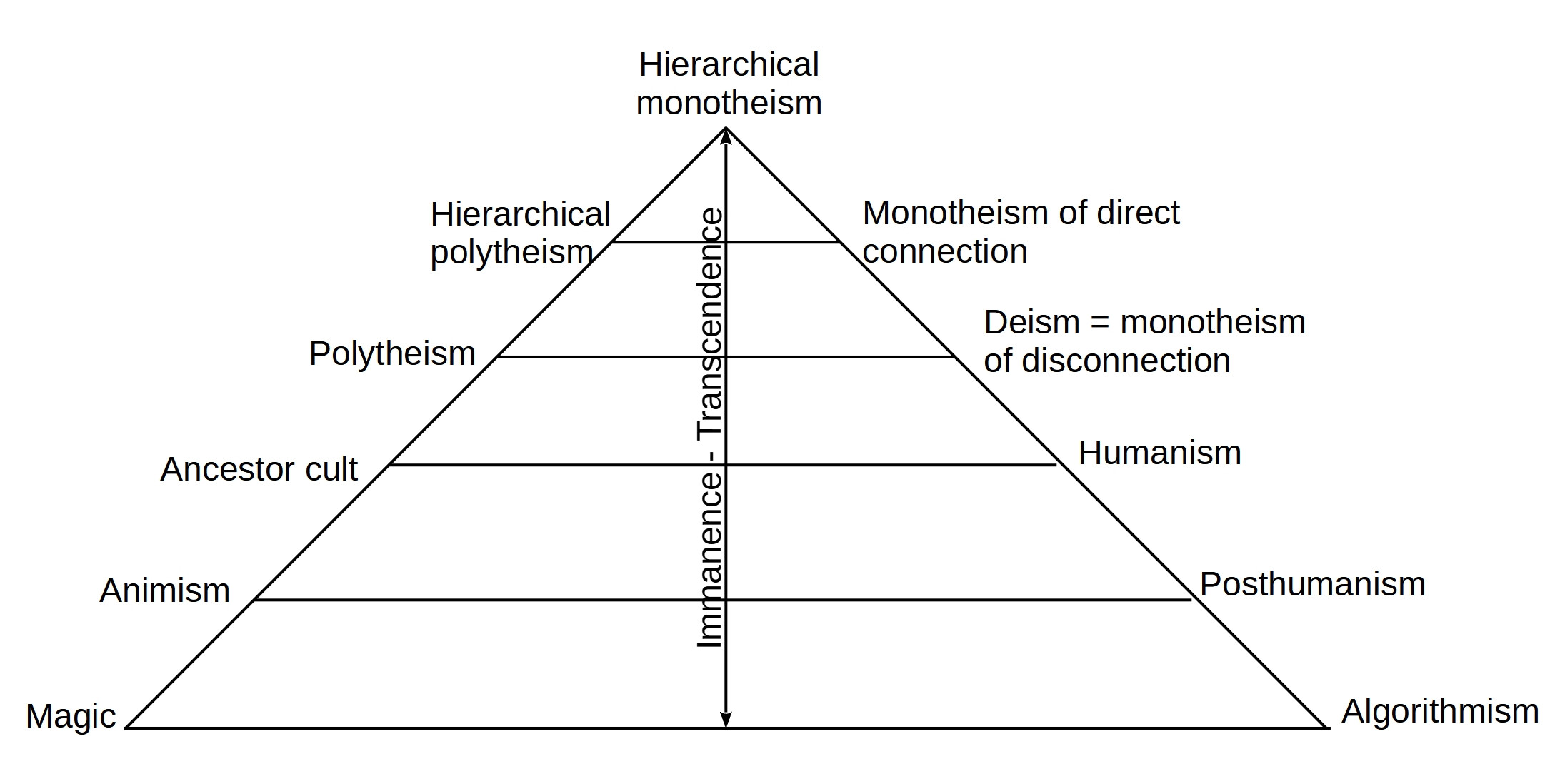

Finally, the third scheme describes the development trajectory of forms of false consciousness in relation to personification and depersonification. Greater detailing in a number of ideological formations allows us to observe a regularity according to which the personification of uncontrollable forces increases in the direction of unification and transcendence, reaching its apogee in Catholic Christianity and culminating in algorithmism as a generalized behavioral-neuroeconomic ideology, followed by a non-ideological practical-materialistic worldview, conditioned by the sublation of frustrating uncontrollable factors.

Let us trace the pattern according to which the personification of uncontrollable forces increases in the direction of unification and transcendence, reaching its apogee in

3. Critique of humanisms. A subsection of critique of forms of false consciousness, distinguished mainly due to its cultural relevance, is the critique of humanism. Humanism, the belief that everything in the world is divided into inanimate things that exist according to the laws of causal determination — and humans who have free will and do not obey the laws of physics — is obviously an unscientific conception. A scientific, that is, materialistic description of the world presupposes the universality of the description and the exclusion of metaphysical pseudo-explanations, which is any personification — spiritual, divine or human.

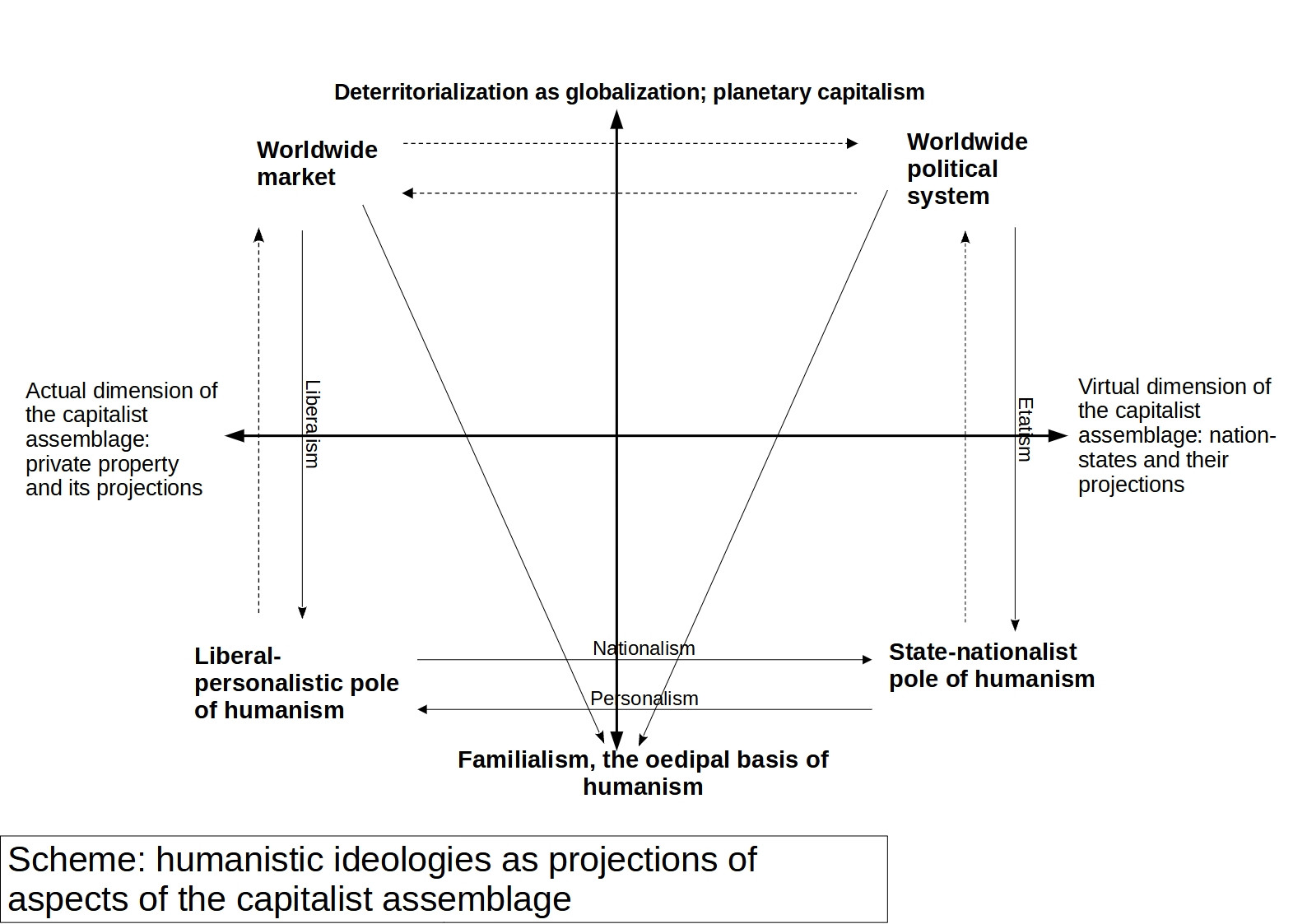

However, it is not enough to point out the ideological nature of humanistic personification; it is important to be able to naturally explain the emergence of personification phenomena from the motion of impersonal material assemblages. The morphism scheme describes a set of projections in which the actual complexity of the social system is reduced in actual and virtual ways, thereby giving rise to the liberal-personalistic and national-statist poles of humanistic ideology — as well as familialism as a synthesis between them. The knot of the Oedipal family, as the truth of capitalist ideology, generated by the global machinery of financial markets and nation-states, was the key theme of the first volume of "Capitalism and Schizophrenia". We can now go further than Deleuze and Guattari in understanding the structure of humanistic and family ideology, as well as the menchanisms that emerge it.

4. Critique of ISA and Cognitive Environments. The next step in comprehension the forms of false consciousness and the mechanisms that generate them is the study of the system of ideological and repressive apparatuses of the state as macrosocial spaces of subjectivation — as well as cognitive environments as microsocial spaces of reinforcement of conditioned reflexes that directly form, consolidate, support and destroy certain ideological forms of behavior. A materialist view of ideology involves a focus on specific forms of ideological behavior, as well as on the direct and indirect positive and negative reinforcements through which multiple social bodies flow. At the same time, cognitive distortions that arise and collapse in the flows of subjectification can be well described by means of coinciding dialectics, namely the coding of environments of contact.

***

Applied sections of philosophy — gnoseology, ethics and aesthetics — are knowledge about how to cognize the world, how to change the world, how to enjoy the world. In summary: entertaining yourself with Nature.

4. On gnoseology

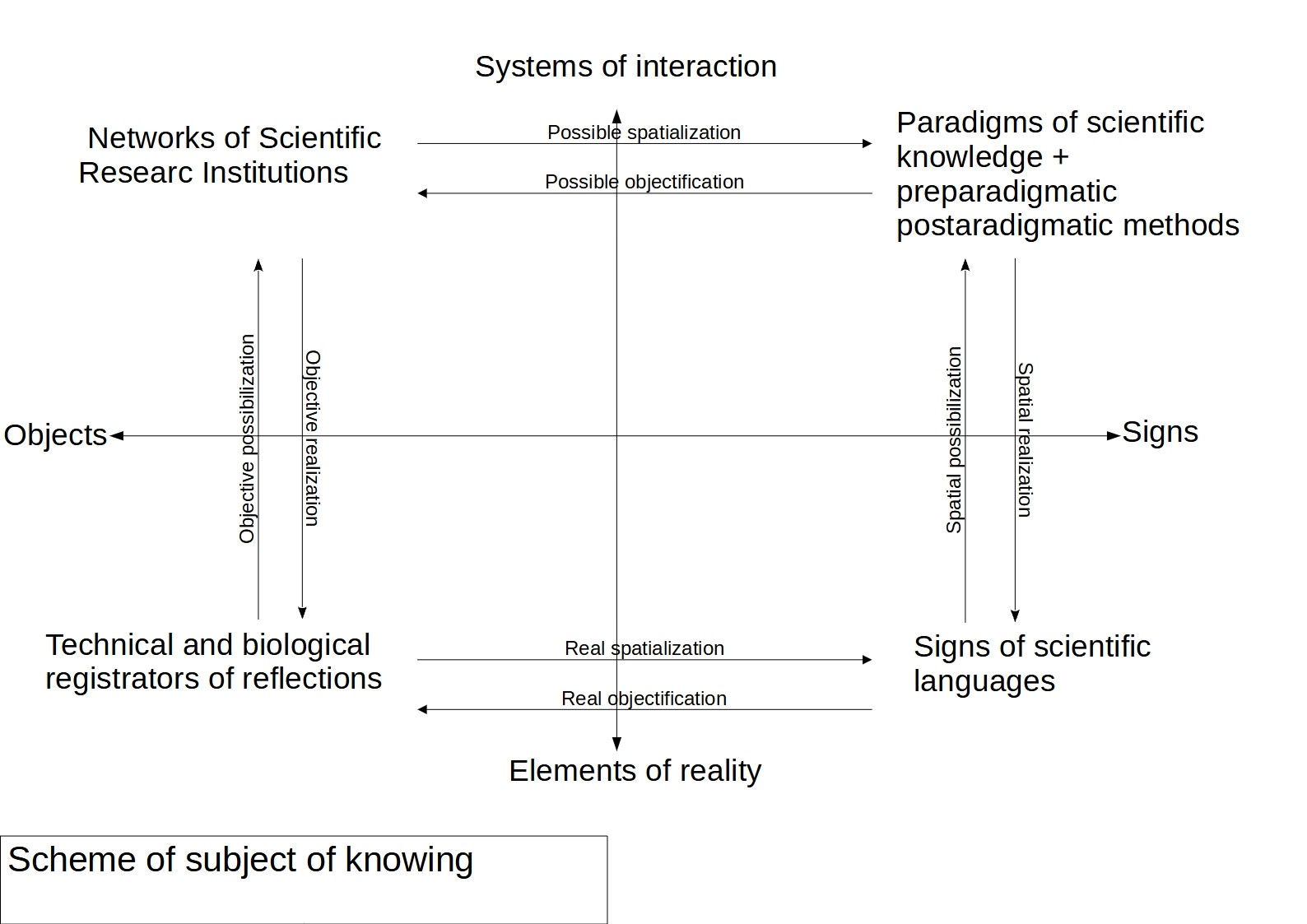

Just as the history of philosophy determines the categorical system, and it determines the possibility of critique of metaphysical and ideological delusions, in the same way critique makes possible adequate knowing of the world, which constitutes the subject of gnoseology — the philosophical theory of knowing. The essential point of gnoseology is the clarification of the subject-object structure of cognition, as well as the process of its realization. Let’s look at them step by step.

1. The question of the subject of knowing today remains entangled by the remnants of humanist metaphysics, since by default the subject is understood to be a biological organism separated from the surrounding nature by the surface of the skin. Thus, the human-nonhuman division can be characterized literally as subcutaneous-percutaneous. With such specification, the delusional nature of humanist metaphysics becomes obvious.

On the contrary, based on the universal assemblative division of reality, we can point to the actual, virtual, realistic and possibilistic dimensions of the cognitive assemblage. Let us accept as an actual dimension of scientific assemblage empirical and experimental knowing — the recording of reflections of colliding multiplicities of objects in which their properties are appears; and as virtual — symbolic descriptions of empirical data.

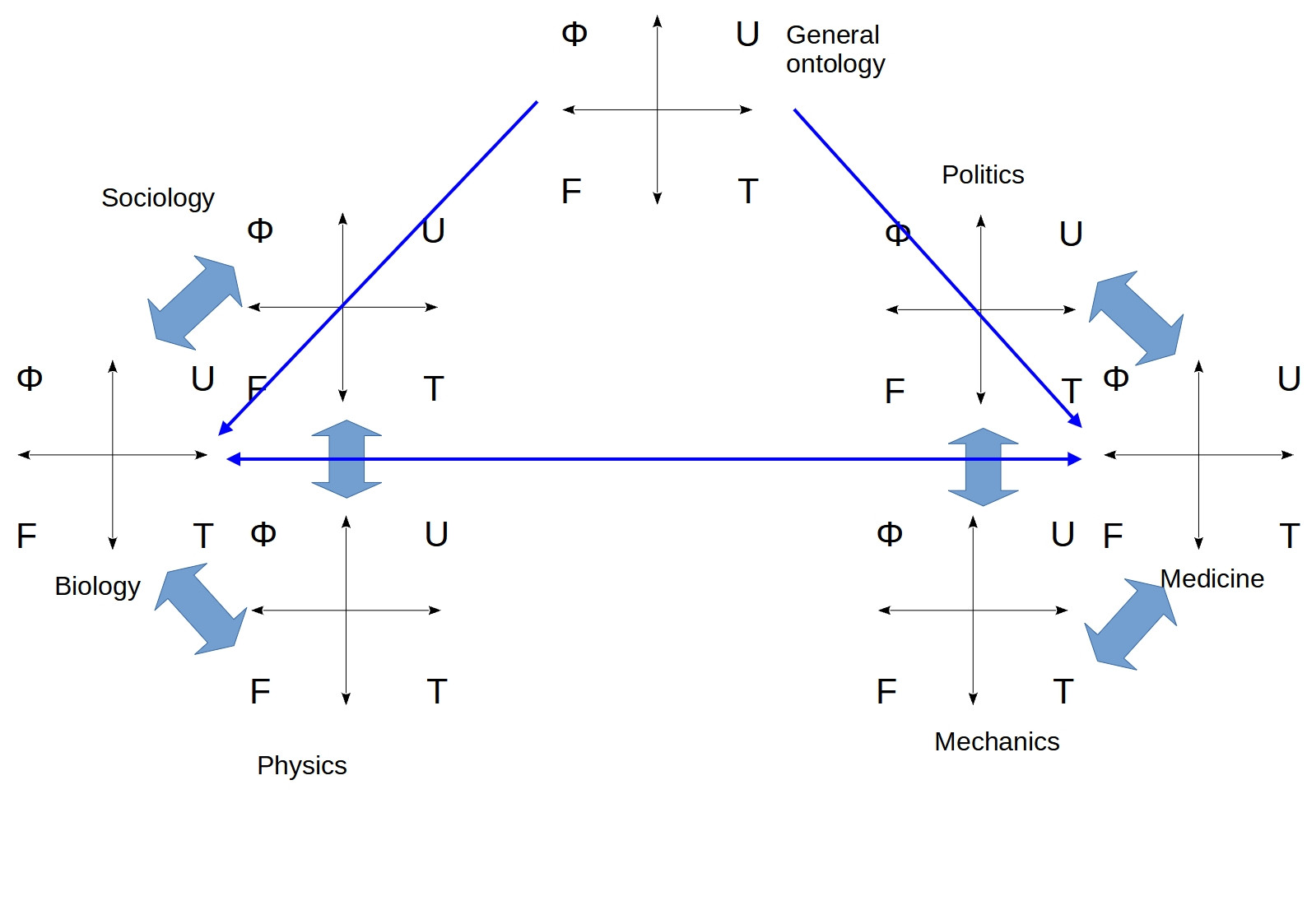

F — concrete experiments, instruments and research teams that record reflections of moving matter;

Φ — systems of research institutes, universities, laboratories, in which scientific machines that record reflections are included as elements;

T — concrete verbal, terminological and formulaic descriptions of fixed reflections of moving matter, constituting meaning spaces in which the processes of experimentation take place;

U — systems of scientific knowledge, including pre-paradigmatic, paradigmatic and post-paradigmatic components, the space of which the functioning of research institute systems is carried out, and in which concrete symbolic descriptions are included as elements.

Reflection theory developed in this way has a number of advantages, including:

1.1. Sublates the modern-european division of rationalism-empiricism, noting experimental and logical knowling as two aspects of the same scientific assemblage;

1.2. Eliminates the metaphysical figure of human as the pseudo-center of knowing, destroying the basis of anthropocentrism in the theory of knowing;

1.3. Sublates the question of the activity of consciousness in a non-humanist way. In fact, if cognition is a process of reflection, that is, the transition of the form of one object to another when they collide, then the activity of consciousness, expressed in instrumental activity, is not an act of free will, but a determined consequence of the re-reflection of forms accumulated by the nervous system, passing from memory through motor neurons, muscle contractions and instrumental mediation on this or that material. At the same time, conscious and active collectives act in relation to instrumental sets as copying machines, reflecting the forms of material objects and organizing the material according to the reflected form.

1.4. Allows to think the material substance itself as a subject and as a ultimate cause of knowing.

2. The object of knowing, as well as its subject, is the material substance itself in certain forms of its manifestation. The infinity of nature is given to us only through finite modes, among which we can identify the three most essential. Deleuze and Guattari characterize them as follows:

"Summarily and traditionally, we distinguish three major strata: physicochemical, organic, and anthropomorphic (or "alloplastic")."

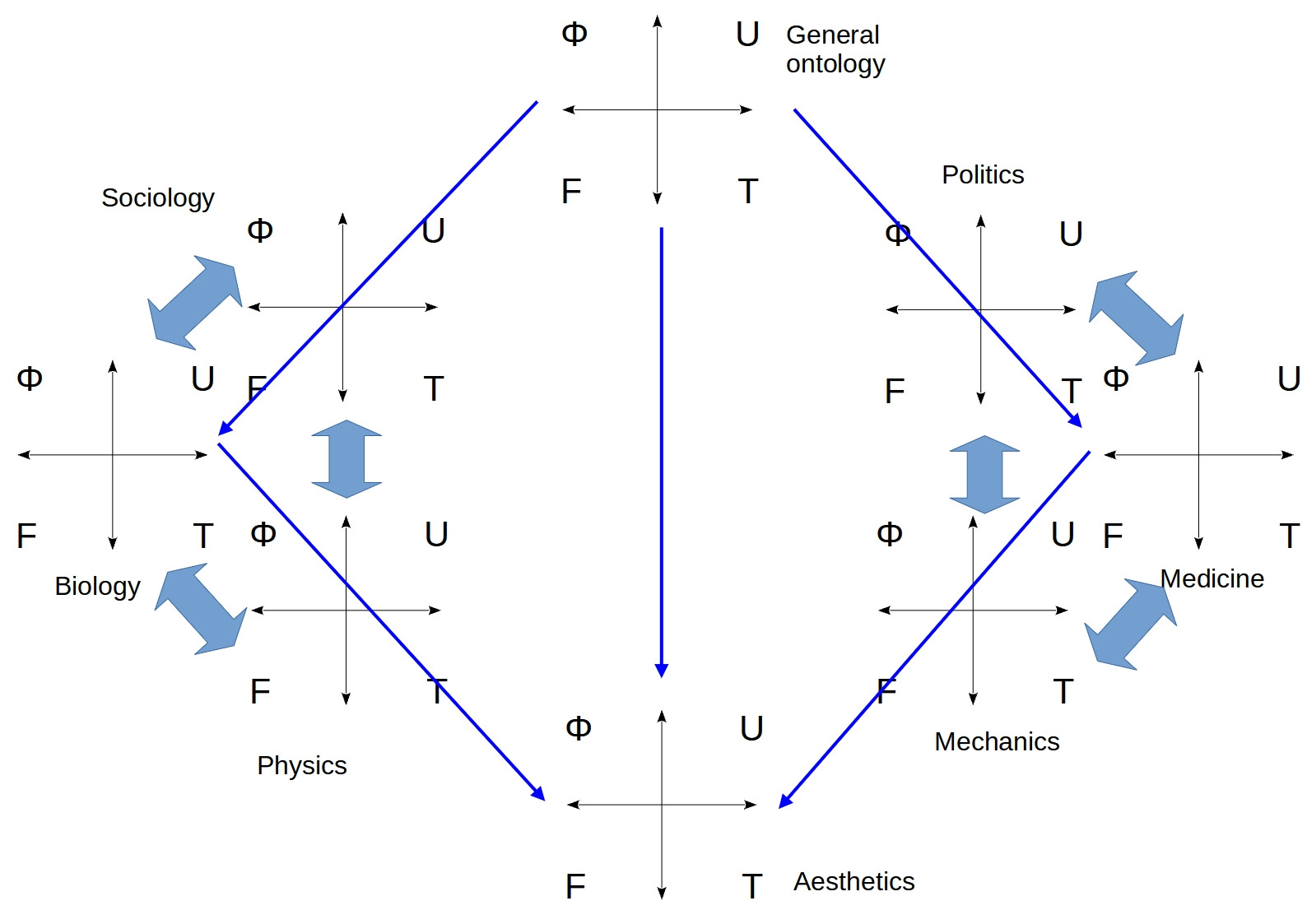

Accordingly, the series of sciences, once outlined by Auguste Comte, can be reduced to three main ones: physics as the research of heteropoietic assemblages; biology as research of sympoietic assemblages; and sociology as research of instrumentally and symbolically mediated sympoietic assemblages. Natural isonomy that includes this stratas as particular modes are extends infinetly outside from scientifically knowing universe and is the source of new discoveries on the frontier of social cognition. Therefore we should to understand this sciences — physics, biology and sociology — in the prospect of its future extension that makes our present knowledge only particular case in some universal regularities. In 16th century Nicolaus Copernicus proposed that society, earth and solar system is not unique and singular objects but parts of major population of similar systems. The principle of mediocrity are generalized Copernicus’s ideas for any material assemblages and conequented from fundamental ontological principle isonomy — Nature as reality of all possible. In this prospect physics, biology and sociology it isn’t only empirical sciences of anthropocentric world — but sciences of extending spectrum of possible physics, biospheres and societies in all possible worlds.

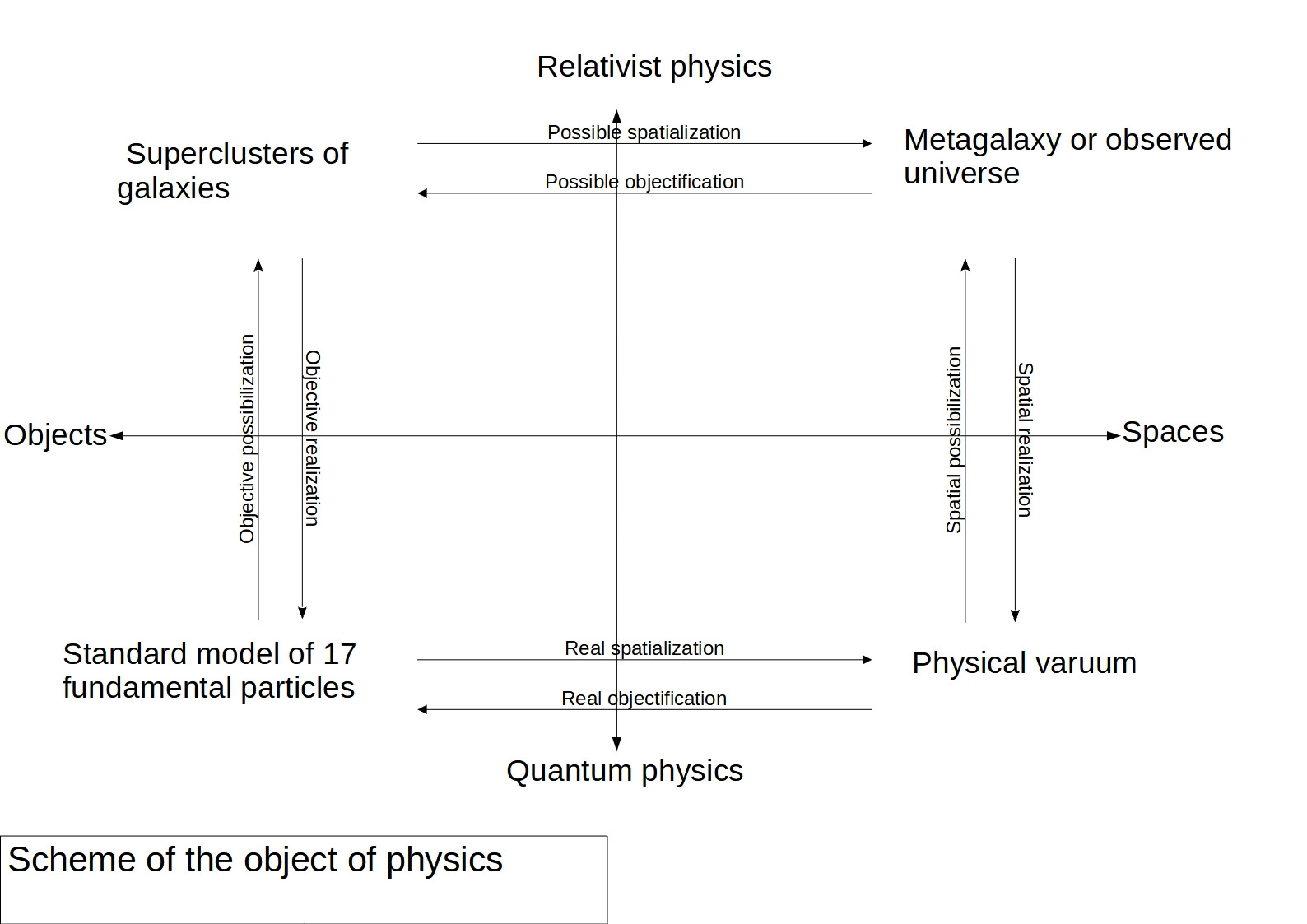

2.1 The physical mode of the motion of matter can be described in general on scheme of assemblages as follows:

F — elementary particles according Standard Model — fermions that divides to quarks (Up and Down, Charm and Strange, Top and Bottom) and leptons (Electron and Electron neutrino, Muon and Muon neutrino, Tau and Tau neutrino), and bosons that divides to vector bosons (gluon, photon, Z boson and W boson) and scalar bosons (Higgs boson). This set of particles is a key to understanding of the Periodic table and all physicochemical micro-interactions because nuclons that constituate line of chemical elements are consist of quark triplets (u, u, d = proton; u, d, d = neutron) — and electrons that is a type of lepton particles. But there is no law of nature that would exclude the possibility of the existence of arbitrarily smaller particles than those known to contemporary science.

Φ — large-scale systems of interacting objects are includes molecular clouds, stars, planets, black holes, galaxies and their clusters. The largest known system of objects is the multitude of bodies that make up our universe, which arose 13.8 billion years ago.

T — physical vacuum and forces of interaction — weak, strong, electromagnetic, gravital; and other virtual constants that characterize motion of the stuff in this universe.

U — large-scale spaces of interaction are includes relativist landscape of 4-dimensional space-time curvatures and has diameter 93 billions of light-years. Size of our universe as largest of known spaces is not largest os possible — there is no law of nature that would exclude the possibility of the existence of arbitrarily greater spaces than those known to contemporary science.

2.2 The biological mode of the motion of matter is built on top of physical and chemical processes as a sympoietic process of self-organization of objects and spaces that are reproduced during this process itself. Here we should point out the theory of autopoeisis, which arose in the 2nd half of the 20th century based on the work on nonequilibrium physics by Ilya Prigogine, as well as the work of the Chilean cyberneticists Maturana and Varela. The advantage of their views was a general description of the processes of self-organization of matter; The disadvantage is an obviously idealistic interpretation of one’s own discoveries, namely, the absolutization of the moment of self-sufficiency of systems. In their opinion, systems create themselves and the world around them through observation, so that the world and the environment do not generate systems, but are their product. However, this interpretation does not stand up to either theoretical or empirical critique. In the first case, the law of causality is violated; they themselves are indicated as the causes of systems. In the second case, the fact of abiogenesis, as well as the influence of the environment on self-organizing systems, remains inexplicable. For example, a grain of wheat is a self-organizing system, unfolding into an ear — but growth and development are impossible without heat, water and sunlight. To assume that the grain somehow magically creates the sun — and this is precisely what follows from a literal reading of the theory of autopoeisis — is absurd.

Thus we arrive at a more materialist and dialectical theory of sympoiesis, in which the growth and development of systems is a product of the interaction of the systems themselves and the environment that precedes them. While the process of such interaction, which includes both system and non-system elements, can be called an assemblage.

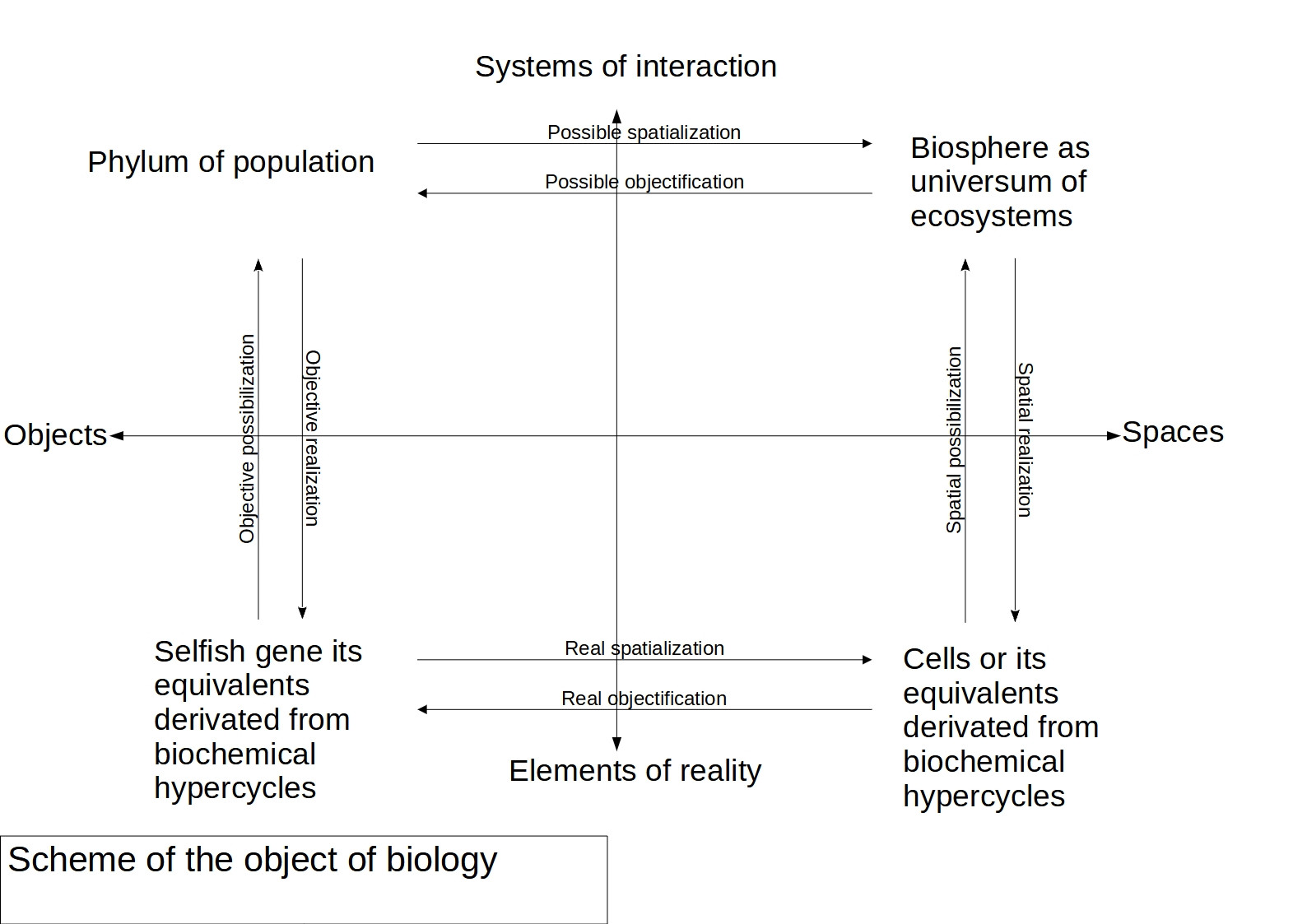

The biological strata can be described in general on scheme of assemblages as follows:

F — flows of genetic expression and energetic catabolism and anabolism;

Φ — phylum of that populations fills universum of biosphere;

T — cells as organell-matrix complexes;

U — complex of ecosystems that constituate biosphere of our planet.

As for the physical mode of the motion of matter, there is no law of nature that would exclude the existence of any other forms of life in eternity of Nature.

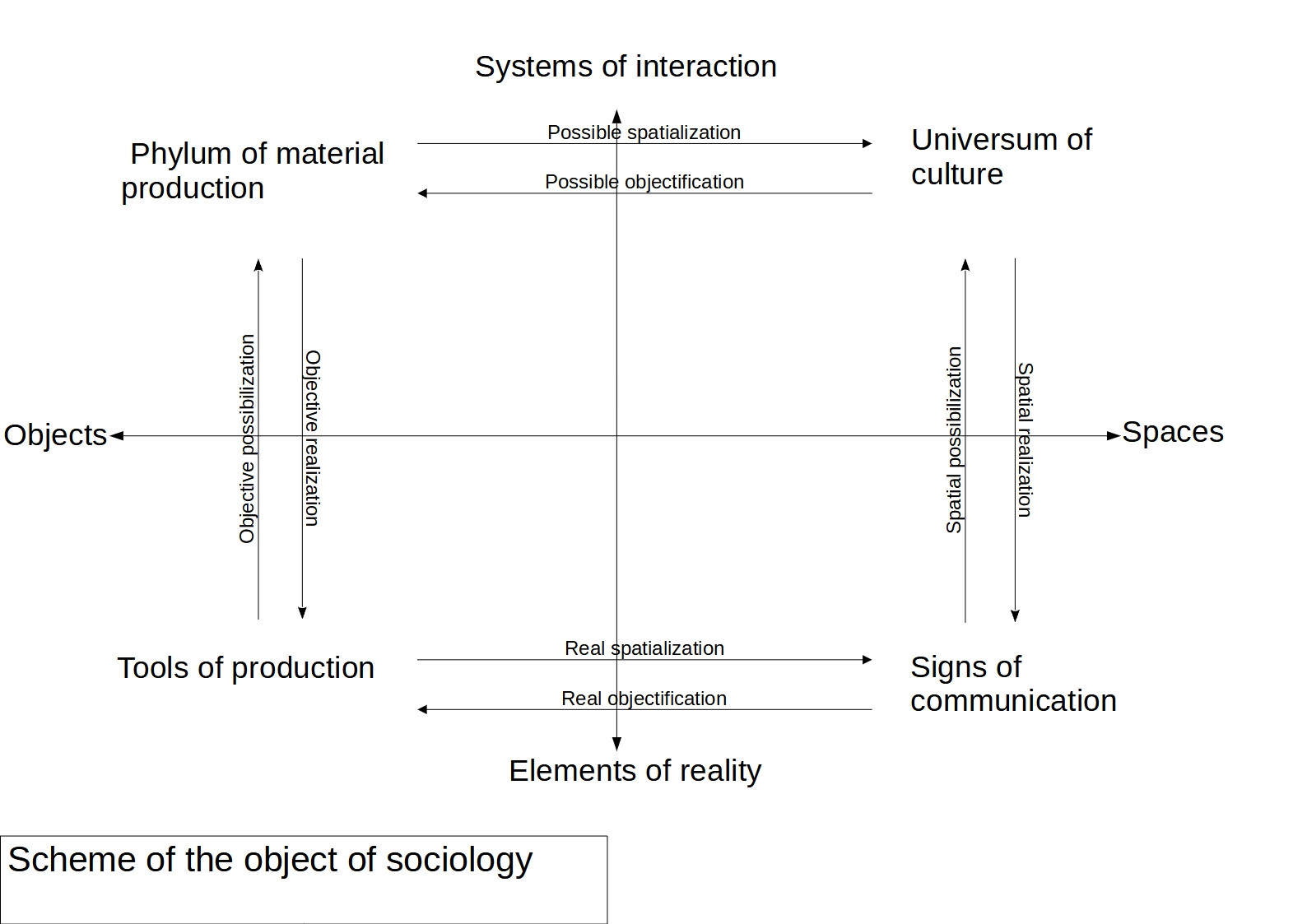

2.3 The social mode of the motion of matter is an instrumental mediation of sympoietic processes of self-organization of objects and spaces, reproduced during this process itself. This means that the reduction of social matter in the dominant ideology to the activity of human bodies and/or minds is devoid of any raison d’etre. Object-oriented ontologies, which include all vulgar Deleuzianism, only extend this spaceless view to various levels of social organization. The point is to discard the old system of observation in favor of observing the spatial distribution of tools and signs as mediators of social assemblages — and their final elements. The social strata can be described in general on scheme of assemblages as follows:

F — singular tools and instruments as mediators of activity;

Φ — social industries or chains of fabrics;

T — singular signs as mediators of thought;

U — cultural universes or spaces of signification

3. Coinsidence of subject and object in the process of knowing. Rejecting humanist ideology and with it realistic metaphysics, we come to a monist and materialist view of the nature of society and knowing. In this case, the processes of cognition are constructed, but they is based not on social, not artificial, but on natural, objective groups of differences: between objects and spaces, elements and systems, causes and effects. Thus, our gnoseological position can be characterized as natural constructivism.

5. On ethics

Ethics is philosophy applied to problems of acquiring material wealth, or enrichment, just as gnoseology is philosophy applied to problems of acquiring knowledge. Avoidance of understanding this simple truth is a hallmark of metaphysical philosophy, leading to suffering, poverty and death of its bearers. This beggarly, suffering and death-dealing pseudo-ethics is the essence of the religious worldview. Therefore, in religions, various kinds of martyrs, sufferers, holy fools and other persons who was poor in body and poor in spirit are especially revered.

Another prejudice of metaphysical theories of ethics is the idea that ethics has as its subject the inner world of human and care for him, without including care for the body and the conditions of its existence. Since we, as materialists, suggests that existence is the only immanent reality, any discussion about otherworldly reward is meaningless, which means that the well-being of the body, and not the salvation of the soul, is essential for us. So, cultivating feelings such as humanity or piety, from our point of view, will be an immoral meaningless act — while morning fitness, brushing your teeth or a proper diet, which improves health, will be ethically appropriate actions.

In this sense, it is useful to return to the original guidelines of new European morality, to the Cartesian-Spinozist synthesis, in which a rationalist program for the development of ethics was outlined. Thus, in his Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect, Spinoza writes:

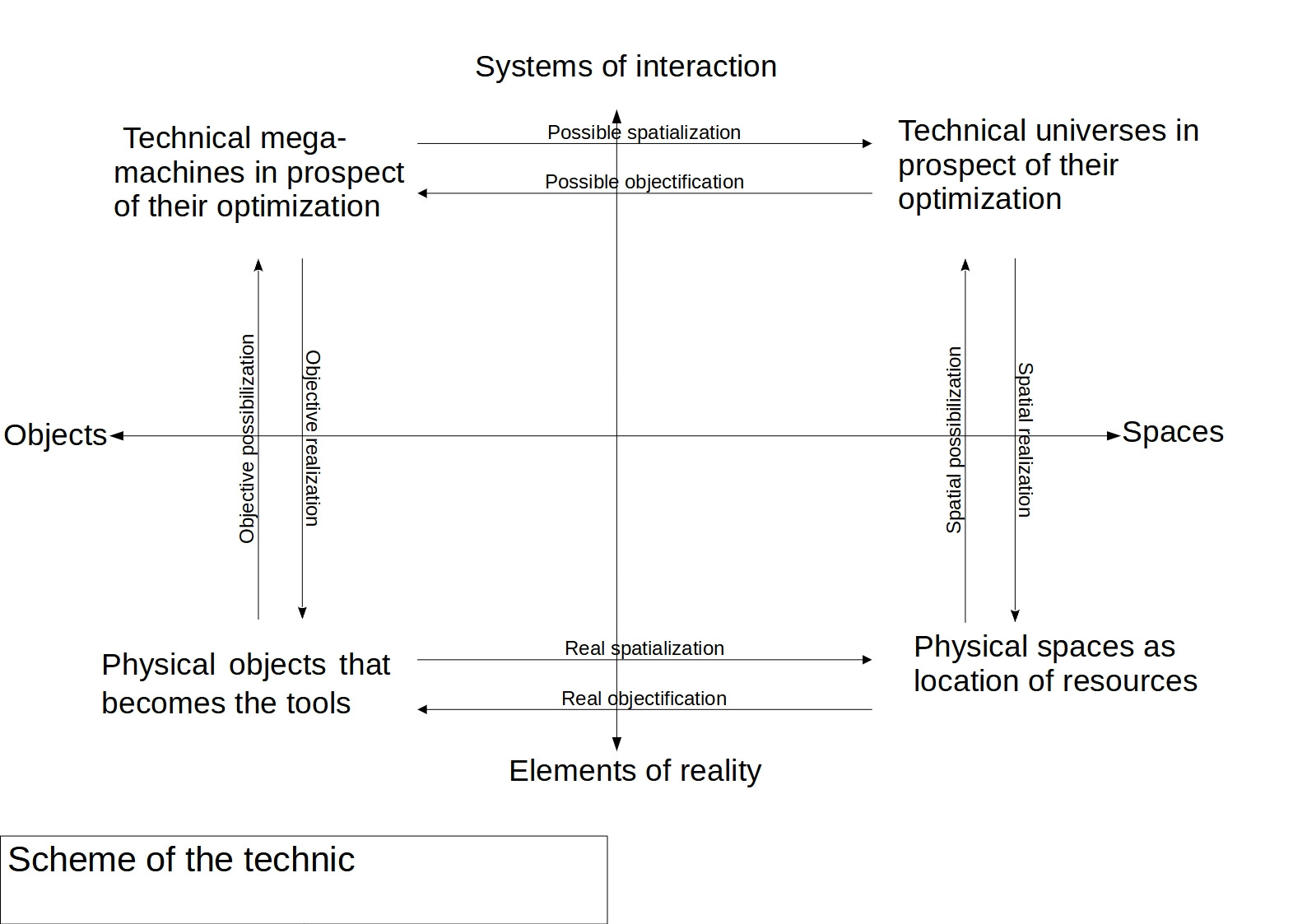

"This, therefore, is the end towards which I strive — to acquire this nature and to endeavour that others may acquire it with me — that is to say, it is essential to my happiness to try to make many others understand what I understand, so that their intellect and desire may entirely agree with my intellect and desire. In order to achieve this end, it is necessary' to understand so much of Nature as may be sufficient for acquiring the desired nature; then to form a society such as is desirable for enabling as many people as possible with the greatest ease and security to acquire it. Furthermore, we must pay attention to Moral Philosophy as well as to the science of the education of children, and because health is by no means an insignificant means to the attainment of this end, the whole of medicine is to be studied. Because also many things which are difficult are rendered easier by art and we can thereby gain much time and comfort in life, Mechanics are by no means to be despised.

But above everything a means of healing the mind must be sought out, and of purifying it as much as possible at the outset so that it may happily understand things without error and as completely as possible. Hence everybody can now see that I wish to direct all the sciences to a single end and purpose, ' namely, that we may reach that highest human perfection of which we have spoken."

Post-Soviet Ilyenkovist philosopher Andrei Maidansky notes the following about this: “Ethics, medicine and mechanics are three branches of Cartesian “tree of philosophy”, corresponding to the three kinds of existence, society, living and inanimate nature. Medicine was the science of “life in general” (the term “ biology" has not yet appeared)".

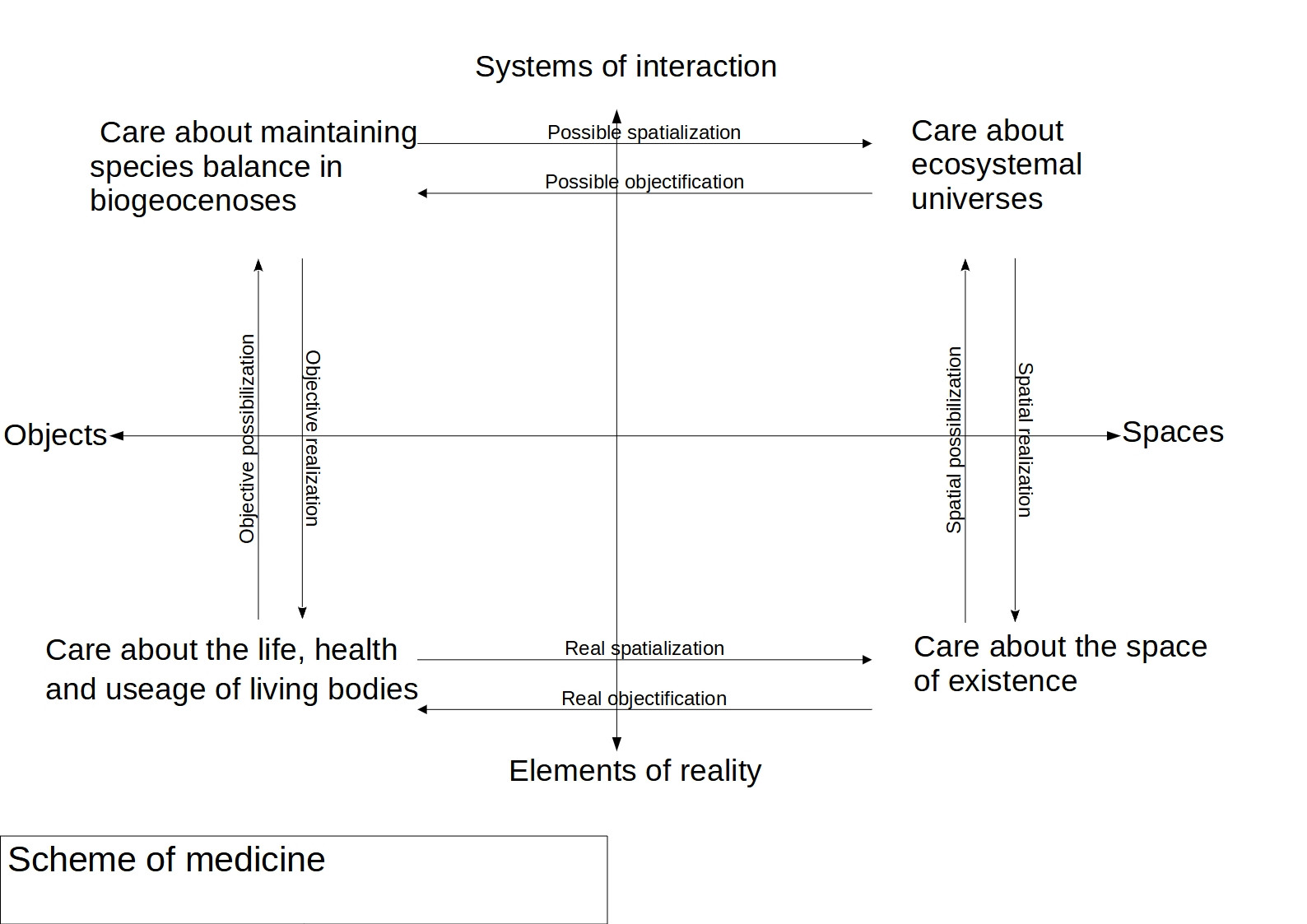

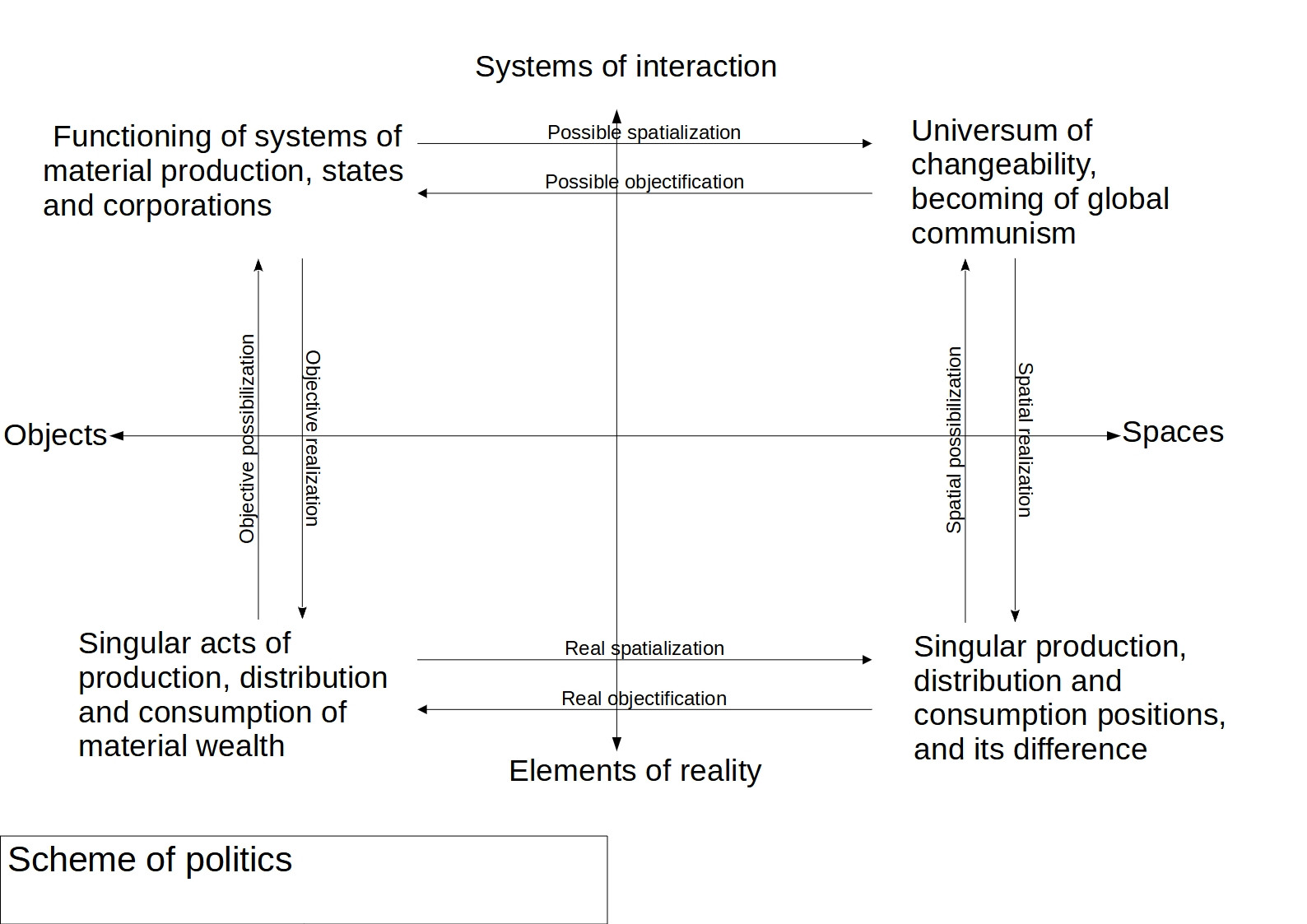

The most important point that we can draw from this reasoning is the symmetry of gnoseology and ethics as two areas of applied philosophy. So the triple division of the subject of knowledge — physical, biological and social nature, will correspond to the triple division of the subject of ethics — technology, medicine and politics. In this case, the subjects of both areas will also be symmetrical to each other.

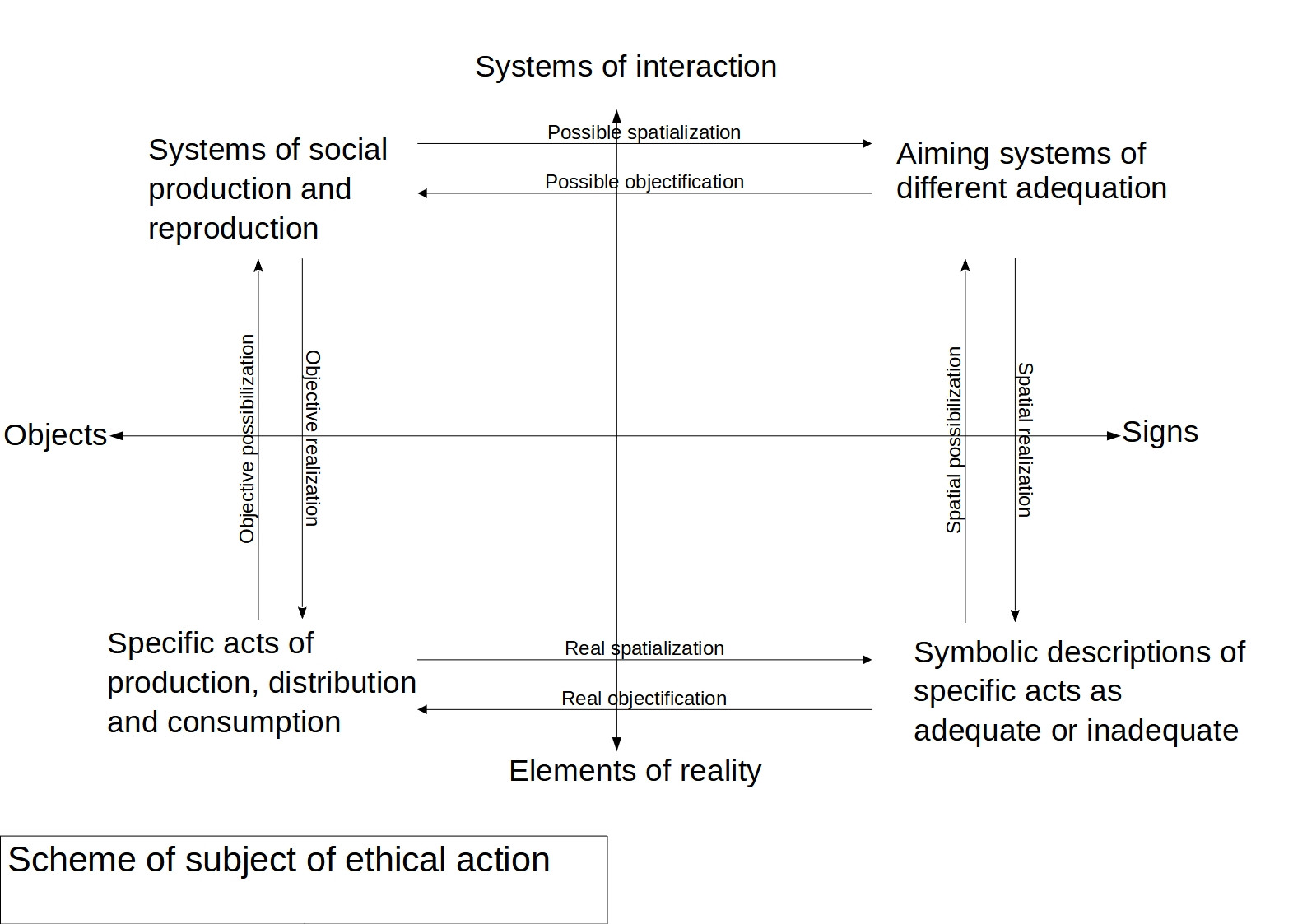

1. The subject of ethical action is the same as the subject of cognition, but taken from the point of view of existence, and not cognition. This leads to the following division:

F — specific acts of production, distribution and consumption, constituting moments of material existence;

Φ — systems of social production and reproduction;

T — symbolic descriptions of specific acts as adequate or inadequate;

U — aiming systems as possible spaces along the framework of which socialized bodies move.